In an age of divisiveness, Ron Bloom shares advice and experiences from a career building consensus.

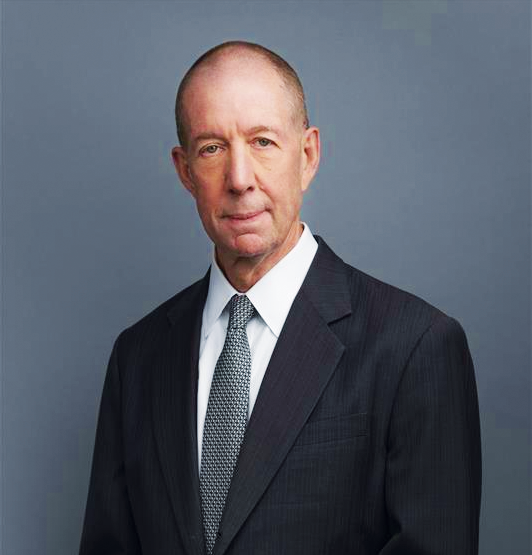

Ron Bloom is a Democrat, a one-time top official of the steelworkers’ union and a former high-profile member of the Obama Administration. Yet when President Trump in 2018 needed to fill a vacancy on the United States Postal Service board, he nominated Bloom.

That choice might have been surprising if not for Bloom’s well-known approach to negotiation. “In every stop along the way, whether it was working for a union, or a private equity firm, or the federal government, I’ve tried hard to ask myself, ‘How do we find common ground?’” says Bloom.

Bloom has been especially successful at finding common ground between management and labor, a talent he developed soon after graduating from Harvard Business School. Joining Lazard Freres & Co. as an investment banker, he focused first on mergers and acquisitions, then became a key negotiator on behalf of unions amid a crisis regarding retiree healthcare. At many companies, commitments to fund retiree healthcare costs had been rendered nearly impossible by rising healthcare costs and an increasingly lopsided ratio of retirees to active employees. As leaders of some companies threatened to kill those obligations amid restructurings, some labor leaders called for to-the-letter fulfillment of the original contract.

As an investment banker, Bloom understood that cash-strapped companies couldn’t produce liquidity out of thin air. But he also understood the value of equity, and on behalf of unions he negotiated agreements that relieved or modified the companies’ obligations to provide retiree healthcare in exchange for equity, among other things. Besides promising a future to companies facing extinction, these agreements gave workers a sizeable stake in that future. In case after case, the agreements over time worked to the benefit of both sides, making Bloom the Obama Administration’s natural choice to try saving General Motors and Chrysler amid the financial crisis of 2008-09.

Dubbed the “Car Czar,” he and his team coaxed, prodded and at times demanded sacrifice from management, employees, retirees, bondholders, auto dealerships, suppliers and other competing interests. At the time, the common ground he delineated wasn’t wildly popular with any of the parties. But over time the wisdom of the bailout became evident in record profits and saved jobs. When he left that job in August 2011, President Obama said, “For the past two and a half years, Ron Bloom’s leadership and expertise has helped us put America’s automakers back on the road to recovery, launch new partnerships to make our manufacturers more competitive, and set aggressive fuel economy standards that will save consumers and businesses money at the pump.”

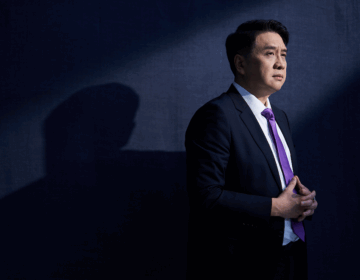

Today, Bloom is a Managing Partner and Vice Chair in Brookfield’s Private Equity Group, responsible for investment origination, analysis and execution across North America. In that capacity, he remains committed to the search for common ground. “Talk to all sides—that’s what I’ve been trying to do in my tiny corner of the world, and I’m certainly not the only one who’s trying to do it,” Bloom said in a conversation with the Review. “A lot of smart people are trying to do it. We are a bit out of favor today. But I still think it’s the right answer.”

In the following conversation with Brunswick Review Editor Kevin Helliker, who in 2009 covered the auto bailout for The Wall Street Journal, Bloom describes a career devoted to “serving as a bridge between capital and labor.”

“We persuaded folks that we weren’t there to grind an ax. We were there to solve a problem. Our goal was the common good.”

First, allow me to say thanks on behalf of friends of mine who work at the GM plant in Kansas City, Kansas, my hometown. Friends in management, and friends on the assembly line. How did you get those typically opposing parties to agree?

What did Samuel Johnson say? “An imminent hanging concentrates the mind.” It is easier to get someone to sacrifice if their best alternative is even worse. Yes, you are giving up something. But you will do meaningfully worse if the whole enterprise fails. That element is crucial to the formula.

A second crucial element is that there must be a sense that everyone’s pitching in. No one wants to be the idiot. No one wants to be the only person giving. The measurement of sacrifice may not be identical. How do you measure a bondholder getting less than is claimed to a worker keeping or losing a job?

It is apples and oranges. But psychologically, there must be a sense of what I call rough justice. In the absence of any perfect calibration, people need to feel a sense of rough justice.

A third element is that the party meting out justice—in this case, government—must have credibility. By sitting and spending significant time with every stakeholder, our little team was able to persuade them that we really were seeking a fair deal for all concerned.

What’s important, especially in light of today’s polarization, is that we made no secret of our individual backgrounds or biases. I never pretended that I didn’t work for a labor union, or that I didn’t also work on Wall Street, which at that moment wasn’t very popular. No one on our team pretended. We persuaded folks that we weren’t there to grind an ax. We were there to solve a problem. Our goal was the common good.

There’s no shortage of quotes out there from management representatives and Republicans praising you as pragmatic rather than dogmatic.

Look, I’m a Democrat. I don’t pretend otherwise. But is everything that Trump does evil? Maybe Trump has a point sometimes. Conversely, maybe Joe Biden did a few good things. We have to hope that people who believe in this noble experiment called America will step forward, try to lower the temperature and look for common ground.

A lot of people in their individual worlds already do it. Here and there at the local level, good things are happening. But they don’t get written about because they’re not very interesting, they don’t draw subscribers on TikTok, YouTube, Instagram or whatever. Americans are still incredibly big-hearted. But the bigger picture is kind of scary. Abraham Lincoln famously said we should appeal to “the better angels of our nature.” At the top of either political party, there ain’t a lot of better-angel appealing going on.

Wasn’t the auto bailout a bipartisan rescue, President Bush handing it off to President Obama?

That is a way underreported story of how our democratic system ought to work. A month after the election, in December of ’08, let’s not forget how dark it looked. General Motors ran out of money. Not figuratively. Literally. Chrysler too. Amid the larger financial markets, the credit markets were closed. General Motors couldn’t have gotten debtor-in-possession financing. Literally, no one would have provided it.

It’s not that those two automakers would have gone into bankruptcy without help from the government. It’s that they would have had to liquidate. Every job eliminated the next day, every dealer out of business the next day. The ripple effect would have been catastrophic for the US economy.

The person in charge of our nation’s response was Henry Paulson, Secretary of the Treasury under President Bush. Mr. Paulson, whom I had the privilege of meeting during the transition, did exactly the right thing. He created TARP (the Troubled Asset Relief Program) and gave General Motors and Chrysler a lifeline.

Mr. Paulson said, essentially, “Here’s a bunch of money that will hold you until the next administration gets its bearings.” He understood that his party had lost the election and that therefore it was not proper for him to design the details of the restructure. That was both courageous for him to do and a correct way to think about democracy: “My team lost. I got a new guy coming in. I’m going to let him solve this problem,” not in any bad sense of throwing him the problem, but in understanding that you don’t make a consequential decision as a lame duck.

He provided the automakers with enough money to last until March 31st, which was enough time for us to get in our seats and make some initial decisions about what to do.

“We have to hope that people who believe in this noble experiment called America will step forward, try to lower the temperature and look for common ground.”

Could that work today—catastrophe bringing opposing sides together?

I am squarely of two minds. There has been a lot written about the long list of issues on which there is 80% agreement, and then a whole new bunch of important issues if you drop down to 70%. I consume that information and I buy that argument because I’m a patriot, I’m American and I don’t want our country to be squabbling at such high volume.

But we have evolved to a place where both parties believe it is in their interest—and they might be right, unfortunately—to accentuate the negative. Social media thrives on it. I think the media is guilty too. Controversy sells clicks and column inches both.

Before long everyone says, “You know what? I can raise more money, if instead of calling them the opposition, I call them the enemy.” Or instead of him just being wrong, he’s evil. That can be a tough environment in which to negotiate agreement.

In a 2022 article in the Yale Journal of Financial Crises, you talked about relational versus transactional negotiating.

There’s buying a house and building a house. If I sell you a house, I’m never going to see you again. We’re going to have no relationship down the road. It’s a one-time event. If you pay more, I get more. And vice versa. There’s no second-order consequence, so we are highly incented to do nothing but maximize our advantage.

Building a house is different. Hiring a builder is a little like getting married, at least for a while. You’re going to be together for a long period of time. And there are hundreds and hundreds of decisions they’re going to make that you will have no visibility to. A contract, I don’t care if it’s 10,000 pages long, cannot cover all eventualities in building a house. You have to decide to have a relationship with your builder, and in a relationship you don’t steal a nickel every time you can, or they’re going to do that back to you.

How do you know if the beams are 16 inches or 15.8 inches apart? Are you going to measure them all? In a long-term relationship as between General Motors and the UAW, you have to develop trust. And also a certain tact. If in one contract, I take advantage of you, push you too far, to where you have no choice but to give in, what’s going happen next time the shoe is on the other foot? People have memories. So I’m going to invest in the relationship. That takes a lot of trust, and it takes a lot of discipline. It can be hard in a world that values partisan work. But it’s the only way to build something enduring. Over the long run you’d find that that’s the right way to do it.

What we’re doing now, too often in our country, is take everything I can get because I’m in charge now.

What advice would you offer to CEOs today?

It’s complicated to be a CEO today. You try to manage for the long term without knowing the whole thing won’t get turned upside down in three years.

We tell companies, “Invest for the long term. Don’t be driven by quarterly earnings.” But we’re in a political environment that says, “just place your bet according to who’s in charge at the White House.”

If I’m a CEO, I’m thinking, “What you’re telling me about the long term sounds good. But then you dramatically change the rules on me every four years.” It’s a tough time to lead.

Still, I would give the same advice I’ve always given. Think about how this stuff plays out over time. Think about second-order consequences. Think about the fact that employees are your most important asset. Over the long haul, companies that sustain themselves are companies whose employees believe in the vision of the company as something worth creating and building and sacrificing for.

Look, all this stakeholder stuff is out of fashion, and maybe it went too far. But the core insight, that the corporation is nestled in a web of social relations, is still true. Companies that play for the long run are going to do better. Not necessarily next quarter. But as others before me have pointed out, a huge percentage of corporate America is owned by pension funds. Pension funds are the ultimate long-term investors, right?

More from this issue

Navigation

Most read from this issue

Introduction to The Navigation Edition