“Having a zebra as our icon … puts us in a space where we acknowledge our African roots,” says Investec’s Head of Sustainability.

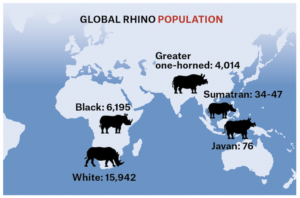

More than a million rhinos roamed Africa and Asia in the 19th century. Today there are only 26,000 left, and three of the five remaining rhino species are classified as “critically endangered.”

The plight of the rhino isn’t unique—one million plant and animal species are at risk of extinction, according to a 2019 UN report. Yet that an animal as large and mighty as the rhinoceros, an almost mythical concoction of horn and armor, is being driven to extinction by human violence and greed somehow conveys the awful urgency of the nature crisis in a way that statistics alone cannot.

South Africa has more rhinos than any other country, making it ground zero in the fight to save them—a struggle that, for the last decade, has included Investec, one of the country’s leading banks and wealth managers.

The rather obvious question: Of all the issues on which it could choose to focus, how did an international bank with more than $53 billion under management land on rhinos?

“I think having a zebra as our icon immediately puts us into a space where we acknowledge our African roots,” says Tanya dos Santos-Ford, Investec’s Head of Sustainability. “It’s almost that, as the zebra company, we would be expected to do something in the space, but that’s not obviously the full story. The rhino resonated because it’s a symbol for South Africa. We saw it as our responsibility to do something about the poaching crisis. A majority of South Africans have some kind of bush experience at least once a year. We live this stuff.”

The fight to save the rhino carries a feature true of the broader nature crisis: it’s a global issue with distinctly local effects. For businesses looking to make a meaningful difference, the best place to start might be their own backyard.

The Rhino as a Keystone

“A rhino is not just a rhino: It is a load-bearing strand in an elaborate ecological web. Just by going about its day, a rhinoceros helps keep its whole environment healthy. Its grazing mows and plows the fields. Its daily walks clear paths through the bush, leaving hard, flat roads for other animals to follow. A rhino’s dung feeds colonies of insects, and birds come to feed on the insects, and other predators come to catch the birds. A rhino is not just a part of the world—it is a world. Everywhere it goes, it moves in swirling clouds of ox-peckers and egrets and guinea fowl. Humans like to pretend that we can stand apart from such elaborate interconnections, from the vast web of nonhuman life. But we, too, are a part of that web.”

—Sam Anderson,

“The Last Two Northern White Rhinos On Earth,” New York Times Magazine.

A criticism of corporate philanthropy is that it tends to care more about generating publicity than impact. To those insinuations Investec can point to their decade-long commitment to the cause and the tangible results of that commitment, from 130 rhinos rescued to education initiatives that have reached more than 50,000 people living in communities along the reserves. What began as a relatively targeted project has since grown to incorporate skills training for local communities, programs to reduce the demand for rhino horn, and cross-sector partnerships to tackle illegal wildlife trade.

In a recent conversation with Brunswick, dos Santos-Ford, a 21-year veteran of Investec, spoke with a fluency and passion for the issue that, if you didn’t know her résumé, would suggest she’d spent her career working for a wildlife NGO. “This isn’t just a project for us, some box-ticking, where we dip in and dip out—that’s why it’s gone on for 10 years,” she said. “We feel a responsibility. If we do the right work, we can make a massive difference. We can help save a species.”

How did Investec get involved in rhino conservation?

In 2012, the rhino poaching crisis in South Africa was particularly extreme. There was a campaign asking businesses to donate money and in return you’d get your logo on a building. That’s not how we like to approach a problem: give some money, walk away.

We started our own project: Rhino Lifeline. It was small. We donated a vehicle to a wildlife vet in the Eastern Cape, which enabled him to respond as the rhinos were being poached.

We quickly realized there was much more that needed to be done, and that it was about much more than just saving the rhino. If you’re talking about tackling climate change, then you’re talking about protecting biodiversity. And rhino are seen as a keystone* species. They’re critical to the overall ecosystem. You take them out and it has a domino effect on other species.

We also knew local communities situated along the reserves had to be part of the equation, and that education would be key. So we partnered with a project that had been piloted in Botswana and brought it down to the Eastern Cape. It taught kids of a very specific age about the importance of conservation. Because if kids go home and tell their parents to stop smoking, they have a lot more impact than the rest of the world telling them to stop smoking.

Originally, we rolled this program out across communities in the Eastern Cape. And then we shifted our focus to the communities alongside the Kruger National Park in Mpumalanga. It’s blossomed since then. We also realized we needed to do more around the actual rescue of the rhino.

Workers on a farm remove a rhino’s horns in an effort to discourage poachers from killing the animals.

When you say “rescue,” are you talking about from poachers?

The majority of the rescued rhino are orphans. Generally, what you see is that a mother has been killed by hunters. If it’s easy enough, the poachers will kill the calf and take whatever horn it’s got. But usually, the calf runs away. And it’s then on its own in the wild, where it won’t likely survive; calves generally stay with their mothers for several years before they move on. You do occasionally get one or two older rhino—perhaps the poachers were scared off.

We helped raise funds for the biggest rhino orphanage in South Africa: Care for Wild. They take most of the Kruger Park’s orphaned rhino. They’ve grown from having just a handful of rhino in 2013 to more than 130 now. A really phenomenal project.

One-hundred thirty sounds like a modest number, but given how decimated the rhino population is, every one really does count.

Exactly. And remember, these are orphans, many of whom would be unlikely to survive. And eight calves have now been born from those orphans.

But, again, it’s important to remember that this is bigger than saving rhino—we call it the economy of wildlife. It’s about bringing local communities into this. People in these communities often struggle to participate in the economy. So we added a skills-development component to Rhino Lifeline. Because valuable skills in these areas are generally around conservation—checking in on the poaching units, for example, or tourism-related skills, since so many people come to South Africa to see the rhino.

“A Reproductive Hail Mary”

The two species of rhino found in Africa—the black rhino and the white rhino—are, confusingly, both gray. White rhinos earned their name from the Afrikaans “weit,” or “wide,” referring to their square mouth. Thought to be extinct at the turn of the 20th century, the white rhino has made an impressive comeback. Yet one of its subspecies is functionally extinct. There are only two northern white rhinos left on earth: Najin and her daughter Fatu, both of whom are unable to carry a pregnancy.

Najin and Fatu live on a conservancy in Kenya, where they are protected by armed guards 24 hours a day. Conservationists have harvested eggs from both rhinos, and used those eggs to create embryos which are preserved in liquid nitrogen. The hope is to one day implant those embryos in southern white rhinos—“a reproductive hail Mary,” as The New York Times described it, but “also the best option left.” In our lifetime we will certainly witness the extinction of the northern white rhino—and, if we are lucky, also its resurrection.

Your involvement seems to have grown as you’ve learned more about the issue.

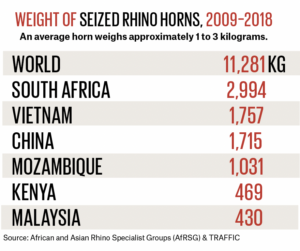

It has. We realized, for instance, there was a lot of great work around the supply side of the poaching crisis, finding ways to prevent the poachers from succeeding. Far less attention was being focused on the demand side. I went to Beijing and Hong Kong to better understand the demand for rhino horn in Asia. It’s massive. And until there’s a mindset change to influence this whole system of demand, you’re going to keep spending lots of money on the supply side.

One of the programs we came up with was to bring young adults from Vietnam to South Africa. They spent a week living in the bush, under the stars, next to a river. It was about trying to connect them with the value of nature more broadly, and the value of the rhino specifically. They were then tasked with raising awareness when they went back to their schools and communities.

In another program we brought Ma Weidu, who founded one of China’s first private art museums, and his team out to South Africa to go to a game reserve, not only to see the animals in the wild

but also really get to know these massive animals. They put their hand in a rhino’s mouth, felt how velvety soft—

Is that safe [laughs]?

It was during a routine procedure for the rhino, where the rhino was sedated. So everyone was safe. Because you’re right, you wouldn’t ordinarily do that to a rhino. They can be aggressive.

But having key influencers share that experience with the rhino … I think you come away struggling to comprehend why anyone would want to butcher a rhino, for the sake of medicine that isn’t actually medicine. You realize that even though they’re so massive and they’ve got these beautiful horns, they are so vulnerable.

Do you have hope?

I have hope when I see how we keep finding new ways and new solutions. And in 2022, the first babies of the orphans were born in a protected area. That certainly gives me hope.

The Rhino Crisis: A Snapshot

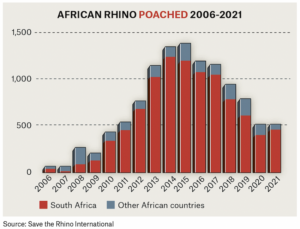

3 forces are largely driving the extinction of rhinos: hunting, habitat loss and poaching.

International trade in rhino horns has been illegal since 1977, yet there continues to be demand for it, particularly in Vietnam and China. Made of the same protein found in human hair and fingernails, rhino horn is a prized ingredient in traditional medicine despite there being no evidence it confers any medicinal benefit. At its peak, rhino horn sold for $65,000/kilogram, costlier than gold or cocaine.

There remains debate on how best to protect the rhinos. Even the most widely discussed options remain controversial: legalizing horn trade, de-horning rhinos and using trophy hunting to fund further conservation.

Thanks to decades of sustained conservation efforts, some rhinos are making a comeback, particularly the southern white rhino. Between 2009 and 2019, the total population of rhinos worldwide grew by more than 6,000.