Brunswick’s Ben Hirschler describes taking part in a COVID-19 vaccine trial as part of the historic global effort to halt the disease.

Above, Kate Bingham, Chair of the Government’s Vaccine Taskforce, is part of Novavax trial in London, one of nine vaccines currently in Phase 3 testing.

It is the last day of London’s Indian summer and I am sitting in a large hospital learning about the risks of participating in a COVID-19 vaccine trial. The weather is about to break—and the coronavirus forecast is also deteriorating, with a second wave of infections spreading rapidly through British cities.

There is a small group of us in the hospital hidden behind facemasks, so it is hard to gauge the mood as we watch a film detailing what to expect and the risks involved. All of us are of a certain age: 56 years and up, to be precise. The trial has already recruited thousands of 18 to 55-year-olds—typically the first age cohort to test a new medicine—and the researchers are now ready to try their invention on us oldies.

Our small group is just a tiny part of a vast international effort to develop vaccines in record time, hopefully to turn the tide on the worst health crisis in over a century. There has been nothing like this global endeavor in the history of vaccines for both speed and scale, and the progress to date has been remarkable. Dozens of vaccines are now in clinical testing and the front-runners have already produced promising preliminary data. They include the one that I will help to test, which was developed by the University of Oxford.

The fact that vaccines are in sight, just months after the new coronavirus was identified in China, is testament to a monumental effort by scientists, drug companies and international groups. But it would not have been possible to get this far, this fast without tens of thousands of people being ready to roll up their sleeves and expose themselves to an unproven shot.

While a small number of participants in our trial are being paid, the vast majority of us will get no compensation. So, what motivates people to take part?

Dozens of vaccines are now in clinical testing and the front-runners have already produced promising preliminary data.

In my case, I can identify three factors. One is a simple desire to contribute to the fight against the pandemic and to push back against a worrying rise in vaccine skepticism. But self-interest also comes into it. By taking part in the placebo-controlled study, I will have a 50:50 chance of getting a vaccine that may—with luck—protect me from a potentially very nasty disease. I will also get weekly home swab tests for COVID-19, enabling me to monitor my health in a way that is unavailable to most people.

The third factor is curiosity. After two decades working as a healthcare journalist, writing frequently about the ups and downs of clinical trials, I am intrigued to find out what it feels like to do something useful and join one.

Filling in the online form earlier in the year to express my interest in participating was the easy part. But now sitting in the hospital waiting for my first injection, the commitment feels more daunting. The scientist in the film we are watching is running through a long list of possible detrimental side effects, from the mild and common (muscle aches, feverishness, headaches, nausea, tiredness) to the very rare and serious (reactions in the nervous system that might cause severe weakness or even death).

It is not the first time I have been in a hospital listening to a list of worrying potential side effects before giving my consent to an intervention. In recent years I have twice heard about the risk of life-changing damage that could arise from routine abdominal surgery. But in those cases, the trade-off was clear: there was a chance to rid myself of discomfort and occasional pain.

This time, I am perfectly healthy, so the risk is harder to evaluate—and that, of course, is the point about vaccine safety. Vaccines are given to healthy people, which means the safety bar must be set extremely high.

Building confidence in the science of vaccines is therefore crucial, not just to encourage participants to enroll in studies but—crucially—to ensure widespread support for eventual public immunization programs.

Despite the overwhelming evidence that vaccines against a host of diseases save millions of lives every year, getting the messaging right in specific cases is not straight forward.

Many Shots on Goal

There are multiple COVID-19 vaccines in development around the world, including more than 40 that are already in clinical trials. Nine of these are in final Phase 3 testing and pivotal data on the front-runners are expected before the end of the year

The wide field increases the chances that at least one—and very likely several—will ultimately prove successful.Initial results are certainly encouraging. But no-one knows for sure how long vaccine protection will last or which groups of people might benefit most.

The vaccines in Western markets that are further advanced include those from Pfizer/BioNTech, AstraZeneca/Oxford and Moderna. While Russia and China have both approved vaccines for emergency use, these products have yet to demonstrate safety and efficacy in big Phase 3 trials.

Six different approaches are being taken to COVID-19 vaccine development—from cutting-edge technologies inspired by genetics to tried and tested methods going back many decades. Scientists are also testing the potential of additives called adjuvants to enhance some of these approaches

RNA/DNA: Genetic code is inserted into human cells, which then use the instructions to make a coronavirus protein.

VIRAL VECTORS: Genetic code to make a coronavirus protein is carried into cells by a harmless virus.

PROTEIN SUB-UNIT: A small piece of coronavirus protein is used to stimulate an immune response.

VIRUS-LIKE PARTICLE: Uses a particle resembling the coronavirus but containing no viral genetic code.

INACTIVATED VIRUS: Coronavirus is disabled by a chemical or radiation so it cannot cause disease but is still recognized by the body.

LIVE ATTENUATED VIRUS: Coronavirus is weakened to reproduce very poorly in the body.

I have grown up in Britain with a National Health Service that I trust, and it is reassuring to find that it is familiar NHS doctors and nurses who are checking me over and administering the injections. Nonetheless, the researchers and medics face significant communications challenges in the light of an increasingly vociferous “anti-vax” movement that questions the safety of vaccinations in general.It is feared the unfounded claims by this movement could lead to significant numbers of people refusing a COVID-19 shot.

Despite the overwhelming evidence that vaccines against a host of diseases save millions of lives every year, getting the messaging right in specific cases is not straightforward. The issue came sharply into focus just two weeks before my hospital visit, when the University of Oxford and its partner AstraZeneca halted new-patient enrollment for their trial after a British participant experienced an unexplained neurological illness. The trial soon resumed in Britain, Brazil and South Africa, following an independent review that deemed the problem was unlikely to be vaccine-linked, although US regulators kept it on hold for longer.

The episode reveals something of a dilemma for scientists and companies: The current global health emergency demands increased transparency from vaccine developers to ensure public support, but the need to protect patient confidentiality and the integrity of scientific research limits the amount of information that can be released.

One thing that is striking is just how meticulous the clinical trial staff are in evaluating every patient. After already going through a lengthy telephone screening to check my eligibility for inclusion in the trial, my initial visit to the hospital still takes more than two hours, during which time we fill in numerous forms, run through my detailed medical history, check my temperature and blood pressure, and take blood samples. I am also given instructions for filling in a seven-day “e-diary” to record my reaction to the vaccine and asked to initial every line of a 22-point consent form before finally getting my injection. One month later, I will return for a booster shot and more tests.

The vaccine we are trialing is made from a weakened version of a common cold virus from chimpanzees that has been genetically changed so it cannot grow in humans. Scientists have added genes to this virus so that it makes COVID-19 proteins called spike glycoprotein. The idea is that if the body recognizes and develops an immune response to this spike glycoprotein it will prevent infection—or at least stop serious disease. Half the volunteers will get this new vaccine and the rest, as a comparison, will receive an existing meningitis vaccine that is not expected to offer any coronavirus protection. Neither group knows which one they are on and nor do the clinicians administering the injections.

Then it is a question of waiting to see what happens. If significantly more people given the meningitis shot become infected with COVID-19, that will show the new vaccine provides protection. However, even with around 30,000 people involved in the trial around the world, it is hard to know when there will be enough infections to prove an effect because this will depend on how much virus is circulating in society at large.

Regulators charged with assessing COVID-19 vaccines want to see, as a minimum, a reduction in the illness rate of at least half—and preferably a lot more. But the bottom line is that we will not know if that can be achieved or exceeded until enough of my peers fall sick. Some early glimpses at the data could be imminent, but researchers—who are keen to compile as complete a picture as possible—are preparing for a long haul.

My last appointment back at the hospital is slated for November 2021.

More from this issue

The WFH Issue

Most read from this issue

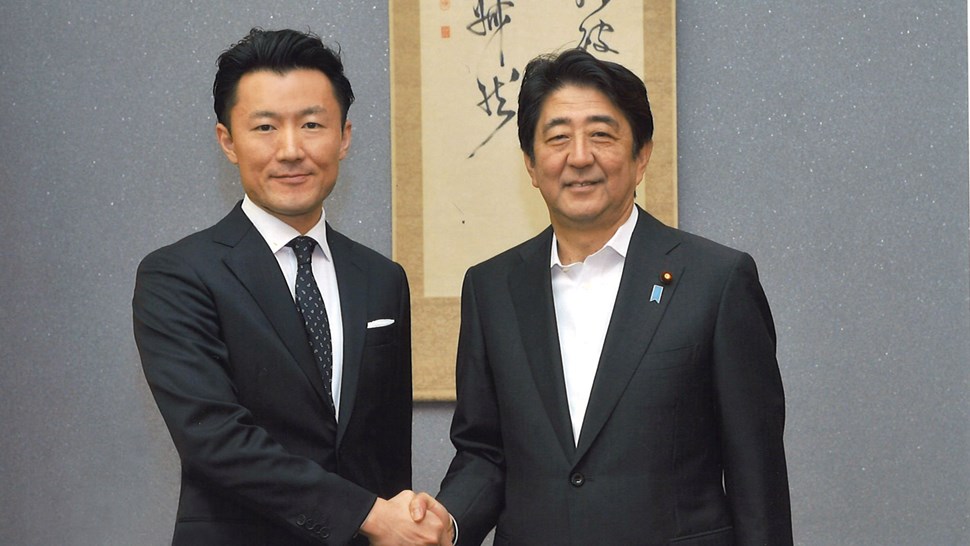

Abenomics: The Sequel