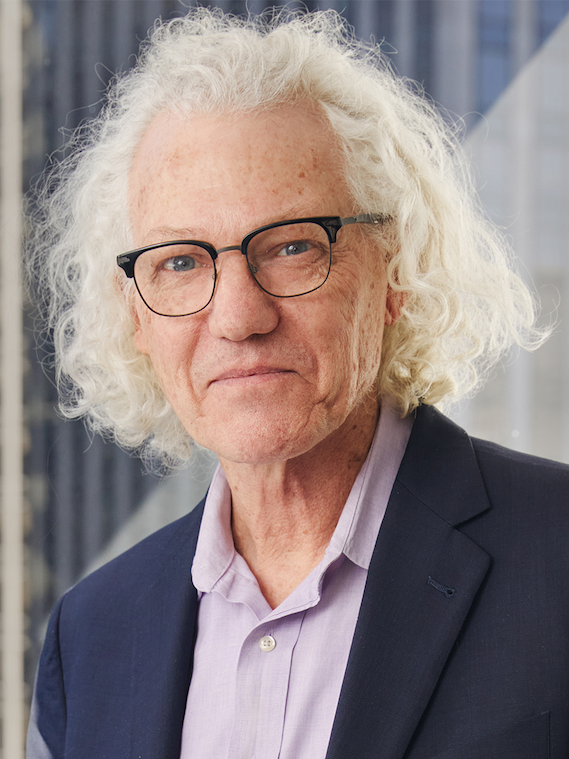

Songwriter and producer Harvey Mason Jr. talks to Brunswick’s Carlton Wilkinson about the demands of steering the Recording Academy and the Grammy Awards.

Harvey Mason Jr., songwriter, producer and CEO of the Recording Academy, attends the 66th Grammy Awards in LA in February of 2024.

Harvey Mason Jr. became CEO of the Recording Academy in 2020, with transformation and flexibility very much on his mind.

“I didn’t see a way we could survive if we weren’t able to change quickly and we weren’t able to react and pivot, to try things,” the career songwriter and producer told us in a recent interview. “And these last two years, there’s been more evolution and change, more innovation in our business than maybe in a long time.”

Modeled on the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the Recording Academy is the nonprofit organization founded in 1957 that awards the gold-plated gramophone statues known as Grammys. Its annual ceremony is the preeminent event in the music world, as the Academy’s voting members—creators spanning all genres and crafts of the industry—vote each year to determine the best work or artist in dozens of categories. It’s a process that needs to be continually examined to stay relevant, Mason says.

“I’ve always looked to push the envelope, to challenge things, in everything I’ve done,” Mason says. “What’s next? How can we do better? At the Academy, we’ve now adopted that same kind of mindset, so there’s not stagnation. There’s actually a bias for action now in everything we’re doing. It’s part of being in this business. If you don’t evolve, you die.”

Under his watch, the organization managed the logistics of COVID, the pressures of the Black Lives Matter and MeToo movements, and frustrations around representation. More recently the rise of AI represents sharp new concerns for creative artists.

Mason grew up around music, the son of musicians, and wrote his first professionally recorded song at 9 years old. In college, he was a basketball star for the University of Arizona, heading to a professional career until an injury took him out of the game in his senior year. Turning to music full-time, he launched a career that has included work with music legends from Aretha Franklin, Quincy Jones and Michael Jackson to Justin Timberlake, Beyoncé and Ariana Grande. He was executive producer for the movies Dreamgirls, Sing and Sing II, and TV productions Jesus Christ Superstar Live! and The Wiz Live!, among many other projects.

“One of my earlier memories was going with my Dad [jazz drummer Harvey Mason Sr.] when he worked with Quincy Jones and Michael Jackson,” he recalls. “Later I had a chance to work with Michael again on the ‘Invincible’ album. That’s something that I’ve cherished my whole life. A lot of what I learned working on his record has shaped my career.”

We spoke to Mason about how his life as a musician informs his leadership at the Academy and the changes yet to come for the music industry.

You’ve been involved in music since you were a child. Has your perception of music changed over time?

It’s definitely changed. I just love listening to music and making music. Once I realized that I had a talent for it, that was all I cared about—not thinking about the big picture or what it means to be a music creator. You just do it because it’s who you are.

Once you become somewhat successful, you start seeing it a little bit differently. Most importantly, you realize the value to others. I began seeing how people were affected personally by music. And that extended over to my life at the Recording Academy.

I joined as a member so I could vote for the awards. But I started realizing that the impact of the music could be amplified and extended. The Academy was a perfect platform to do that; it had been doing it for many, many years. I saw that it was a way to amplify the impact that music has on individuals, on countries, on the planet.

“We can say now that we are very proud to be an organization that listens closely. We are thoughtful, but when it comes time to move, we move.”

Was there a moment where you said, my life is going to be full-time music?

Being around my Dad, going with him to the studio, and my mom also was a musician, I just always thought that’s what I was going to do my whole life. I started writing songs at 9 years old. I wrote a song [“Love Makes It Better”] that Grover Washington, Jr. recorded. And my Dad said, “You know you’re going to get royalties.” And I was, like, “What?” My parents let me use my royalties—they said, “you can buy one thing.” So I bought a model airplane. (LAUGH) The idea of correlating that song—people listening to it and buying it—to allowing me to buy a model airplane was, like, “Oh wow, this is cool.”

So, I had a sense of the business early. Sports came in the middle of that, because I started playing basketball and going to college and then maybe considering playing in the pros. But I always knew at some point, I was going to be working in music.

The average listener and a producer hear songs differently. Is there a similar gap between producer and CEO? Are you hearing music differently now?

Maybe I should be but I’m not. I hear music as a musician, whether I’m in my role at the Academy or I’m sitting in the studio. It’s a benefit that’s been useful to me in my role as a CEO. I can identify with our members, with our creative community, because I am of that community.

On the other hand, there are a lot of other things I’m doing when I hear a song beyond just listening to the music. I am thinking more globally than ever, more holistically and more about how impactful music can be. I’m also thinking about the scary topics, the subjects of intellectual property protection and monetization of art, protecting human creativity. “What does it mean? How do we make sure that people are protected and this art form is celebrated?”

What were the biggest surprises for you as CEO?

As CEO, I got to really see under the hood, how the systems work and how things could be evolved. That was shocking. The Academy does so much that I don’t think most people realize, and I didn’t even realize as a member—we tend to see it as a show or as a trophy, and a one-night-a-year event. There are hundreds of people working all year on hundreds and hundreds of initiatives supporting music people.

I’ve also been surprised to find there’s such a direct correlation between creating music and running an organization. It’s the collaboration, being able to listen, to bounce ideas back and forth and have an open mind. As a music creator, you sit in a studio and bounce ideas off each other, integrating the best ones into the song. I try to bring that to my role as a CEO. I really try and collaborate on a deep level with our staff, our board, our Chair. I’m not saying I’m perfect at it; I’m definitely continuing to grow and work. But that is something that has translated over.

Another thing that surprised me was that there was just so much room to evolve the processes that were in place. Neil Portnow did terrific work as CEO for 17 years before me. But despite the incredible things being done for the community, there were also things that hadn’t changed in years and were ready to be refreshed and evolved.

Part of your emphasis has been a new focus on diversity and on internationalization. And you’re also the CEO of MusiCares, a separate nonprofit founded by the Academy.

The MusiCares organization is such an important organization. We’re going to end up doing almost $20 million in money raised for victims of the LA fires last year. During COVID, I think we gave more than $30 million to people who needed help.

Regarding DE&I—and I know that’s a charged set of letters at this point—the Academy had to become more representative of the community that we were attempting to serve. For me, it wasn’t a political move or a performative move. It was a business imperative. We needed more women. We needed more people of color. We needed certain genres to be better represented, certain geographies, even certain generations. We didn’t have the youth that we needed. That was a big part of evolving our membership.

We also went through an overhaul process of really looking at how we collect our data, how we store membership information, how we vote, how we categorize our services, tracking all that. That was a lot of the work, and it continues now.

We have 25,000 members from around the world and they’re all tied to different music. You look at all the genres of music, there’s factual data out there you can gather and say, “This is how many people listen to this kind of music or that kind of music.” If we’re not reflective of that, then we’re not doing our job.

Is it difficult to steer an entity as old and as large as the Recording Academy, to get that flexibility?

That was one of the early challenges. Some of the processes or even some of the governance that had to be managed to make changes. We’ve come a long way in that regard. Our board and our Chair have to take a lot of credit for that. I am so thankful that I have a good partnership with them. We’ve really gotten to a place with the staff where all the people that are working with us are high performers. They’ve embraced the new culture at the Academy, and together we’ve made huge strides.

We can say now that we are very proud to be an organization that listens closely. We are thoughtful, but when it comes time to move, we move.

Napster in 1999-2000 made all music free to download and share. It roiled the industry. Are you concerned that with AI, technology could again get ahead of us?

I believe technology already is ahead of us because right now, some of the platforms, not all of them, are being trained on copyrighted material. And no agreements are in place for that. So we’re in a similar situation, where the technology has outpaced where the industry is.

It’s going to have to be sorted out. But it’s a lot like sampling. If you remember when artists started sampling records—putting vinyl records on a turntable and rapping or singing over it. The creators of the vinyl records didn’t have a platform to say, “Hey, that’s illegal.” But that was worked out. Today sampling is thriving and creators are getting paid.

I do think there’s work that needs to be done—immediately, quickly, because the technology is moving so quickly. But I don’t feel like it’s going to decimate the industry or put us in a position where all music becomes free.

It will disrupt the way that we have traditionally made music and performed music. The technology allows more people to make music, so there’ll be more music than ever—more songs, more artists performing. That opinion offends a lot of people. It’s been said that you need 10,000 hours to perfect the craft of writing a song or producing a record. I’m one of those people who’ve put in the hours, and now you’re going to be able to do that with a few prompts.

The technology is absolutely here, it’s not going away, and it’s going to be a part of the future of music. The faster we understand it, learn about it, adapt with it and start utilizing it, I think the better off we’ll be—with the caveat that there has to be some legislation or some guardrails in place to protect people.

“There’s actually a bias for action in everything we’re doing. It’s part of being in this business. If you don’t evolve, you die.”

It’s 25 years since the founding of the Latin Grammys. Can you talk about your internationalization efforts?

From our perspective, music is borderless, and it hasn’t always been that way. People can now easily release music regardless of where they’re from and it can reach the world in a day.

We at the Academy feel like it’s our responsibility to honor all music. It’s not just about a certain group of people or certain country. We are all of one community. Our hope over the next two years is to expand where that is manifesting, areas that have thriving creator communities.

With the Latin Recording Academy, we were getting so many submissions for consideration at the Grammys by artists that were from Spanish-speaking or Latin American countries. We said, “We can’t just honor them in one or two categories at the Grammys. That’s disrespectful. It’s not representative.” So we eventually started expanding into a Latin Academy. I could see the same thing happening for other genres in music.

Right now, there’s so much music coming from Africa, from East Asia. The fastest-growing music market in the world is in the Middle East. India has a massive music industry. These are areas we can’t ignore.

There’s always a danger of at least the appearance of cultural appropriation or polluting a culture. Is that a risk you talk a lot about?

Absolutely. You can’t take a nationalistic approach to this expansion. We take a lot of time to meet with the communities, bring on partners. And anywhere we expand to, the expansion will be authentic and will be bespoke to the countries. This is not a plug-and-play situation or copy-paste.

The Latin Academy has its own board, its own leadership and categories. They decide how that organization runs. Any other region, it would be the same thing. If they’re not feeling the ownership, it doesn’t do us any good.

Do you have any leadership lessons or advice you would like to share with the CEOs and executives who are our readers?

Oh, I can’t pretend to espouse CEO lessons to other amazing leaders.

Of the things that have been important to me, one that really made a difference has been choosing the right people and making sure they have the ability to be their best. I spend a lot of time clearing space for different teams, what can I get out of your way so that you can knock it out of the park?

As a producer, I’ve worked with some of the most challenging artists, some of the biggest divas. They’ve seen a lot of producers. I wanted them, when they were done, to say, “I never sounded that good. I was never that comfortable in the booth, that confident.” Even if it’s just you and a sound engineer, you’re counting on the expertise of the other person. You want them at their best.

That’s part of the collaborative process and it’s the same thing I try and do at the Academy. I know as a CEO, you can’t lead or make decisions by committee. But I do believe that getting collaborative feedback from the people you trust and value is an important component of making good decisions.

How can you create an environment of shared responsibility, shared input—a brain trust around the leadership table? I feel like that’s something that’s been very, very important to me.

More from this issue

Navigation

Most read from this issue