It is a problem hiding in plain sight. The world’s medical research system has underfunded women’s health for decades, sidelining half the population and leading to huge gaps in knowledge, as well as a dearth of effective treatments.

Some omissions are jaw-dropping. In the early 1970s, when scientists wanted to explore estrogen’s effect in preventing heart attacks after observing that post-menopausal women were at higher risk, they recruited 8,341 people into a clinical study. They were all men.

That kind of blatant bias would not happen today, but the legacy of decades of underrepresentation means there is a chronic lack of data across women’s health, creating significant barriers to identifying problems, diagnosing illnesses and turning clinical insights into treatments.

As a consequence, conditions like endometriosis and menopause are still poorly understood, with hundreds of millions of women around the world suffering years of excruciating pain and debilitating symptoms, from fertility problems to hot flashes—or flushes—and severe sleep disturbance.

Too often, women complain their problems are dismissed by doctors—a phenomenon some describe as “medical gaslighting.” The result is frequently years of delay in getting a diagnosis and deep frustration with the type of care being provided.

For pharmaceutical companies and the investors who back them, women’s health has certainly been a challenging market. That has been especially true over the past 20 years since the publication in 2002 of results from the Women’s Health Initiative study, which linked hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to a small absolute increased risk of breast cancer and coronary heart disease. The news torpedoed the HRT market overnight and damaged the confidence in commercial returns within the women’s health sector.

“The condition is thought to affect 190 million women globally, causing severe pain, fatigue and sometimes infertility, but it often takes years or even decades to be diagnosed.”

Now, however, there are signs of interest reviving as menopause symptoms and other issues are discussed more widely across the media, and as women demand action to address their chronic health problems, including a reappraisal of HRT. Progress is also being made on the scientific front, offering fresh hope to patients—and potentially providing new opportunities for investors.

“Women’s health today has a much higher profile than it has ever had in the past and women are becoming more vocal. It’s from a low base but it’s going in the right direction,” said Mary Kerr, a biotech entrepreneur and CEO of NeRRe Therapeutics, whose work has helped bring better treatment a step closer.

As a former pharma industry veteran, a pharmacologist, and Co-Founder and CEO of KaNDy Therapeutics (until its acquisition by Bayer in 2020), she has a unique perspective on the opportunities and challenges ahead. The sale of her company gave Bayer access to a new non-hormonal menopause drug candidate that has recently delivered impressive results in pivotal clinical trials. Its future is seen as an important test for a potential new wave of women’s health medicines.

The prize is great. While on average women live longer than men, they spend 25% more of their lives in ill health and disability, according to a report earlier this year from the McKinsey Health Institute and the World Economic Forum. Closing this gap would transform lives. By adding billions of days of healthy living, it could also boost the global economy by $1 trillion by 2040.

The fact that women’s health—apart from breast, ovarian and cervical cancers—is so underfunded compared to conditions that affect both men and women means that even a modest increase in investment could have a substantial impact.

Mary Kerr, biotech entrepreneur and CEO of NeRRe Therapeutics

Currently, the gulf in care between men and women is stark. Research suggests that 80% of men with benign prostatic hyperplasia and 70% of those with erectile dysfunction are diagnosed with the conditions respectively. However, only 40% of women with endometriosis and just 20% of those with vasomotor symptoms of menopause, like night sweats and hot flashes, receive a diagnosis for their problems.

Closing this gender gap requires better delivery of care, increased data collection to correctly assess the impact of conditions and a rethink of scientific inquiry to optimize the understanding of sex-based biological differences.

Incentivizing those changes will need both the pull of potential financial returns for pharmaceutical and venture capital companies investing in the field, and a push from wider society to take the problem seriously.

Increasingly, women are taking matters into their own hands and are providing that “push” by speaking up and championing women’s health through a stream of articles, memoirs and via social media—helped by the activism of celebrities like American actress Halle Berry and British television presenter Davina McCall. As a result, more and more women are being empowered to share about their conditions.

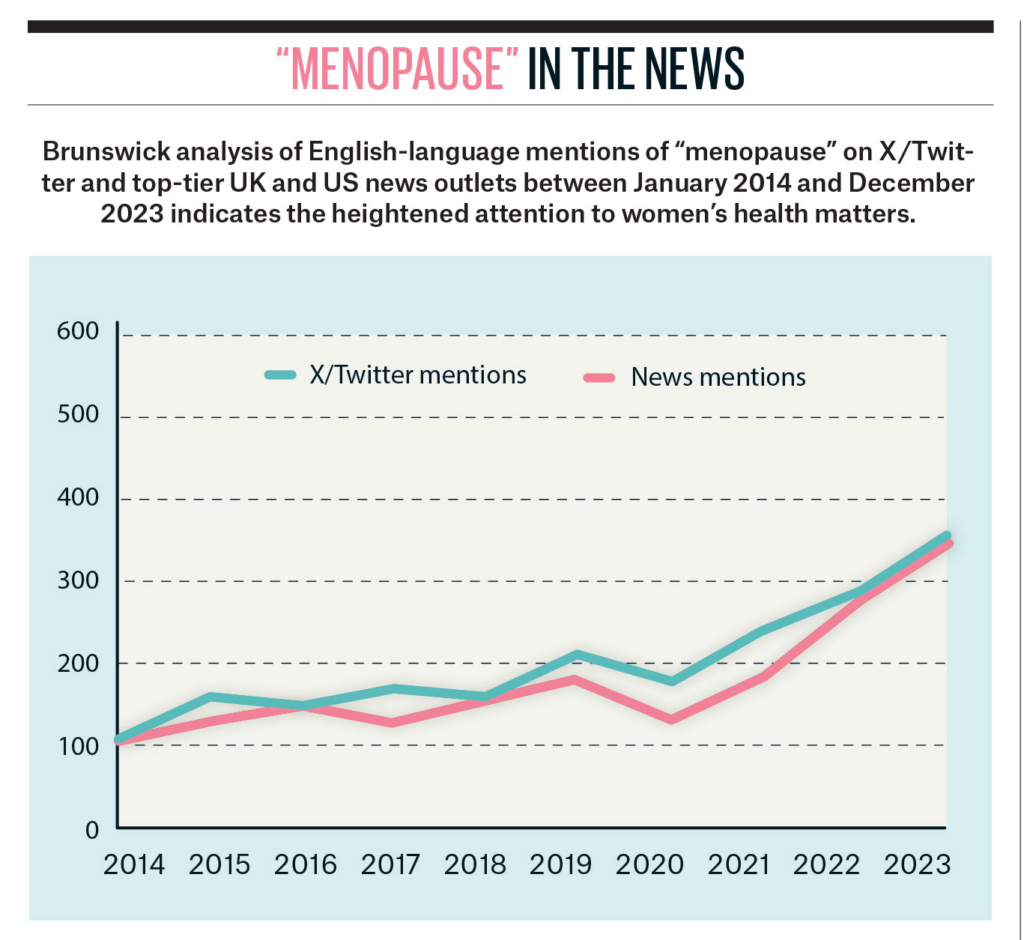

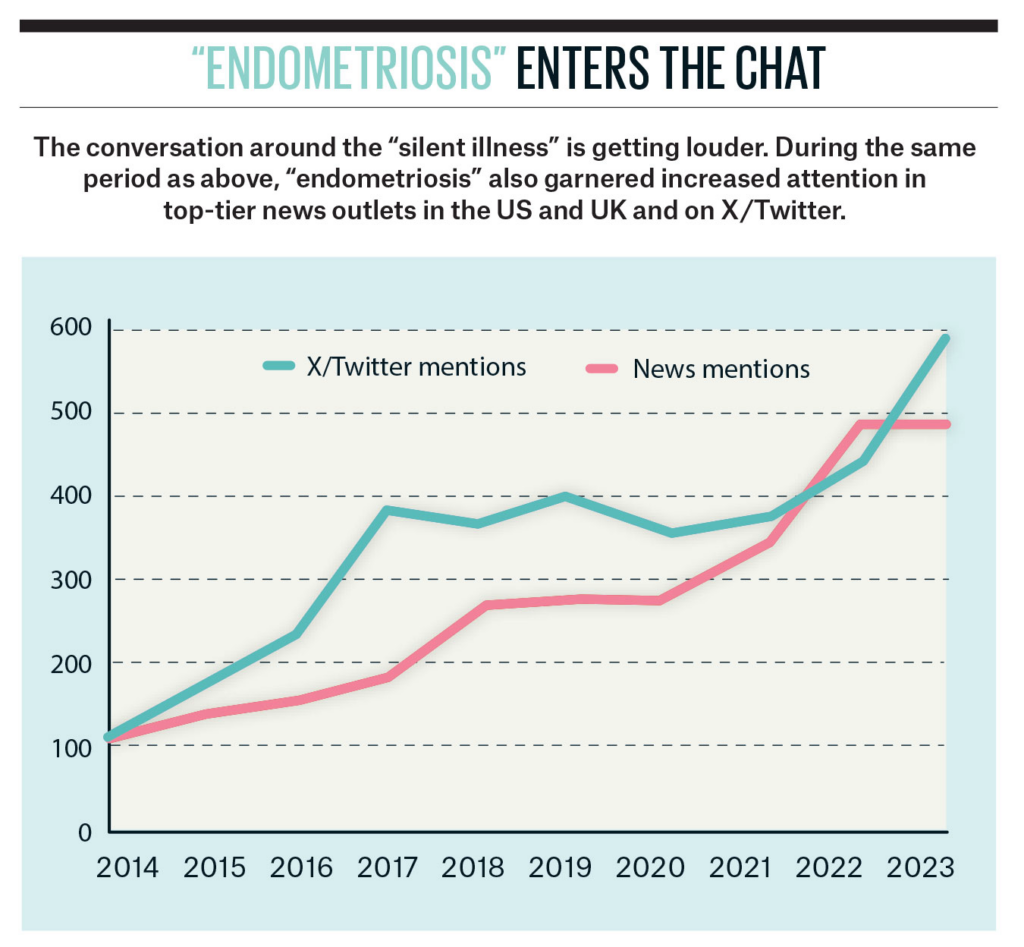

The upswell of debate is reflected in a sharp increase in mentions of women’s health issues in both top-tier media outlets and on X/Twitter, according to data compiled by Brunswick Insight. This is helping to build confidence among investors that there is a significant unmet market to be addressed.

At the same time, women’s health is getting increased attention from governments, with the US launching a pioneering Initiative on Women’s Health Research last year and Britain publishing a Women’s Health Strategy in 2022.

Crucially, there are also breakthroughs in the lab. The success of the first non-hormonal medicines for menopause symptoms has buoyed interest in a long-neglected condition among a few pharmaceutical companies. And advances are being made in other areas, including endometriosis.

“There is clearly a large unmet need and a huge gap in care that is actually costing society money, which means that there are opportunities for new treatments,” said Kerr. “But there is still a long way to go. So far, we’re only seeing the infancy of interest in women’s health.”

Barriers remain. One key obstacle is establishing the value of new treatments to both society and individuals, and calculating a fair price that healthcare systems are prepared to pay for effective symptom relief.

“Menopausal symptoms will not result in hospitalization, but they could result in a woman either not performing at peak capacity or not being able to go to work at all. How do you value that? For the duration of the period during which they are suffering, the symptoms women endure could be as severe as symptoms suffered by people with terminal conditions,” Kerr said.

Another big problem for conditions such as endometriosis, polycystic ovary syndrome and uterine fibroids is the lack of standardized care and uncertainty over the clinical endpoints or outcomes that regulators would want to see to approve a new medicine.

In the case of endometriosis, which occurs when tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows elsewhere in the body, the current absence of clear disease markers can be devastating. The condition is thought to affect 190 million women globally, causing severe pain, fatigue and sometimes infertility, but it often takes years or even decades to be diagnosed. On average, the wait for diagnosis worldwide is over six years.

Ultimately, though, Kerr believes the development of a robust women’s health sector depends on the buy-in of the pharmaceutical industry: “Until pharma decides that it is going to actively focus on women’s health, new and much needed medicines will not be made available to women.”

Geert-Jan Mulder MD, Founder and Managing Partner at Forbion

So, what will it take to move the dial for industry?

Geert-Jan Mulder MD, Managing Partner and founder at life sciences venture capital company Forbion, which funded Kerr’s biotech business, thinks pharma companies will wake up to the potential of women’s health before long. Following an early career as a resident in obstetrics and gynecology, he has long been personally convinced of the need for better therapies.

“Our interest as investors is driven by the unmet medical need and the fact that these conditions affect so many people. In the future, I think this could be an area that gets more attention as pharma companies start to look for alternative sources of revenue, beyond oncology in particular,” he said.

Mulder believes the success of the new non-hormonal medicines will set an important precedent that could demonstrate that this is a serious market for more companies to consider.

Just as critical, however, will be the voice of women in demanding change and pushing back against the notion that they just have to put up with their symptoms. “We need women to mobilize and demonstrate how important this is, just as gay men did in demanding better treatment for HIV,” said Kerr.

Mulder agrees. “If this was affecting men, it would already have been resolved.”