How British police maintain law and order largely without the use of guns. By Kevin Helliker.

During 31 years in law enforcement, Sir Mark Rowley walked the streets as a constable, led a covert unit against organized crime, served as Chief Constable of Surrey’s large police department and ran the UK Counter-Terrorism Policing unit.

One thing Sir Mark never did was carry a gun. “I’ve commanded firearms operations. But I’ve never carried a firearm,” he says. “Nor do I look back and wish for one moment that I’d carried a gun.”

In this respect, Sir Mark typifies the British police. More than 90 percent of UK police officers don’t carry guns. In surveys, the vast majority of them say they want to keep it that way. “Whenever there’s an incident that starts people talking about arming our police, someone takes a survey and most officers say, ‘I don’t want to be armed. That’s not what I joined to do,’” says Sir Mark. “That heartens me. It reassures me that our culture and our heritage are still there.”

At a time of intense scrutiny of police killings in the US—most involving firearms—I found myself marveling at the idea of Britain’s unarmed police. This was not out of any crazy hope that US police might put down their guns. In the most armed nation in the world, an unarmed police force would be defenseless. Nor is it any big secret how police in the UK manage without guns: The UK ranks 127th in guns per capita, according to the 2017 Small Arms Survey, which means that there’s little (though not zero) risk of an unarmed British police officer encountering an armed assailant. Still, a society not that different from America—in fact the nation that gave birth to America—functions with unarmed police. How did that happen? And might there be in it any revelation worthy of consideration here?

After I shared those questions with my colleague Paddy McGuinness, a Brunswick Senior Advisor who formerly served as the UK’s Deputy National Security Advisor, he introduced me via email to his friend and former colleague, Sir Mark.

A graduate of Cambridge University, Sir Mark began his law enforcement career as a constable in the West Midlands Police—a “bobby on the beat,” in UK parlance—and ended it as his nation’s anti-terrorism chief, overseeing a unit that thwarted dozens of attacks. After his retirement in 2018, the Queen knighted Sir Mark for his “exceptional contribution to national security at a time of unprecedented threat and personally providing reassuring national leadership through the attacks of 2017.” His former colleague Paddy McGuinness echoed that praise: “Through my time as Deputy National Security Adviser, Sir Mark was a national asset. He instilled trust and confidence in the public even while we were under attack by terrorists of several persuasions and the police had to use lethal force.”

After leaving policing in 2018, Sir Mark co-founded Hagalaz, which uses new methodologies, gaming technology and crisis leadership expertise to help organizations improve preparedness. He is also Executive Chair of Make Time Count, a new social enterprise digitizing the supervision and reintegration of offenders and other vulnerable groups into communities. And he’s a board member at Quest, a firm that specializes in sensitive investigations especially into global sports integrity issues. He spoke to me from his London home.

It’s a measure of how American I am that I can’t imagine any police officer preferring to work without arms.

On average, less than one police officer a year gets murdered in the line of duty in the UK, out of 120,000 cops. What’s that number in the US?

The average is high enough—about 50—that the murder of a police officer in the US is not big news. Just yesterday, there was a short article buried in The New York Times about the murder of two police officers in Texas.

Right. By contrast, when two young women officers were tragically murdered in Manchester in 2012, that was in the news for ages. It’s still in the news. The government set up a task force to coordinate efforts to tackle the organized crime behind the murders.

Such tragedies are outrageous here because they’re unheard of. If you’re a police officer here, why would you want to change that? I think there’s a concern that you might actually escalate risk by arming officers. In the States, there is data around officers being killed by their own gun after it was taken by an assailant.

“On average, less than one police officer a year gets murdered in the line of duty in the UK, out of 120,000 cops.“

Yes. An FBI report says that between 2002–2011, 28 US police officers were killed by their own stolen guns.

The downsides are serious. Why risk them if you don’t actually need a gun? There’s also the risk of suicide, among police officers and members of their family.

That’s true. A nonprofit that promotes mental health assistance for US police officers reported a record number of suicides in 2019—228—among current and former police officers. And there’s research showing higher suicide rates among gun owners, simply because they have the means to act on suicidal impulses. Still, there must have been a moment in your career as a police officer when you wished you had a gun?

Not really. When I was a newly promoted sergeant, I ended up chasing a guy who’d done an armed robbery who was carrying a gun. I didn’t have one. I was very pleased when he decided to throw it away and keep running rather than turn around. If we were more militarized and armed in UK policing, maybe he would have turned around and pointed it at me. As it was, he threw it away and ran and I was faster than he was because I was fit and he was a drug addict. So justice was done. I’ve had a few knocks and bruises in my policing career, but I’m alive and well.

Did I hear you say the percentage of British police officers carrying guns rose slightly under your watch?

After looking at terrorist attacks as they were developing in other parts of the world, most notably after the Bataclan attack and other Paris events, we decided we needed a larger number of armed officers to deal with such eventualities. At that time, I was in charge of national counter-terrorism, and I discussed that with David Cameron and Theresa May and they gave us extra money to arm us. That might have taken us from 5.5 percent to 7 percent of officers being armed. It was a big deal for us, but it still left well over 90 percent of our officers unarmed.

That small percentage does mean the training levels can be very, very, very high. On my watch, in 2017, we shot dead quite a few terrorists. Do you remember the attack on London Bridge? The terrorists drove over a bridge and mowed down some people. Three guys get out of the vehicle and the three guys are shot by the police. They were shot dead within eight minutes of the police being called.

That was a consequence of changes we’d made in the previous two years, having more armed officers. But still, only 7 percent of your officers are armed, and three roving terrorists are shot dead in eight minutes? I know the NYPD or Chicago or Los Angeles police would be very happy with that outcome.

I’m not suggesting the US could import that. Our armed officers are trained to a far higher level than your average armed American cop because they can be, because it’s a small proportion. Ours are doing five weeks a year of training. When only a small percentage of your officers are armed, you can afford that kind of investment. Every one of our armed officers is actually trained to deal with terrorists who might appear to be wearing a suicide belt.

The training to a higher level means you’re much less likely to unnecessarily shoot a member of the public. We have various training kits in the UK where you take your people through different scenarios, perhaps using a laser gun, and it shows you when they fire and how much they fire, and it improves judgments and decision making.

Without that training, an officer can shoot the wrong person. Or let themselves get tunnel vision where they fail to see a line of innocent people at a bus stop behind the bad guy. Learning to get as much information as possible before you fire, waiting a fraction of a second longer to see that it isn’t actually a weapon he’s carrying. The practicing of that kind of judgment is very difficult, but that’s what our armed officers are trained to do.

Of course, with fewer armed officers, there’s a danger your response might not be quick enough. You have to be able to manage the logistics very carefully when you’ve got fewer armed officers. But we’ve shown we can respond quickly.

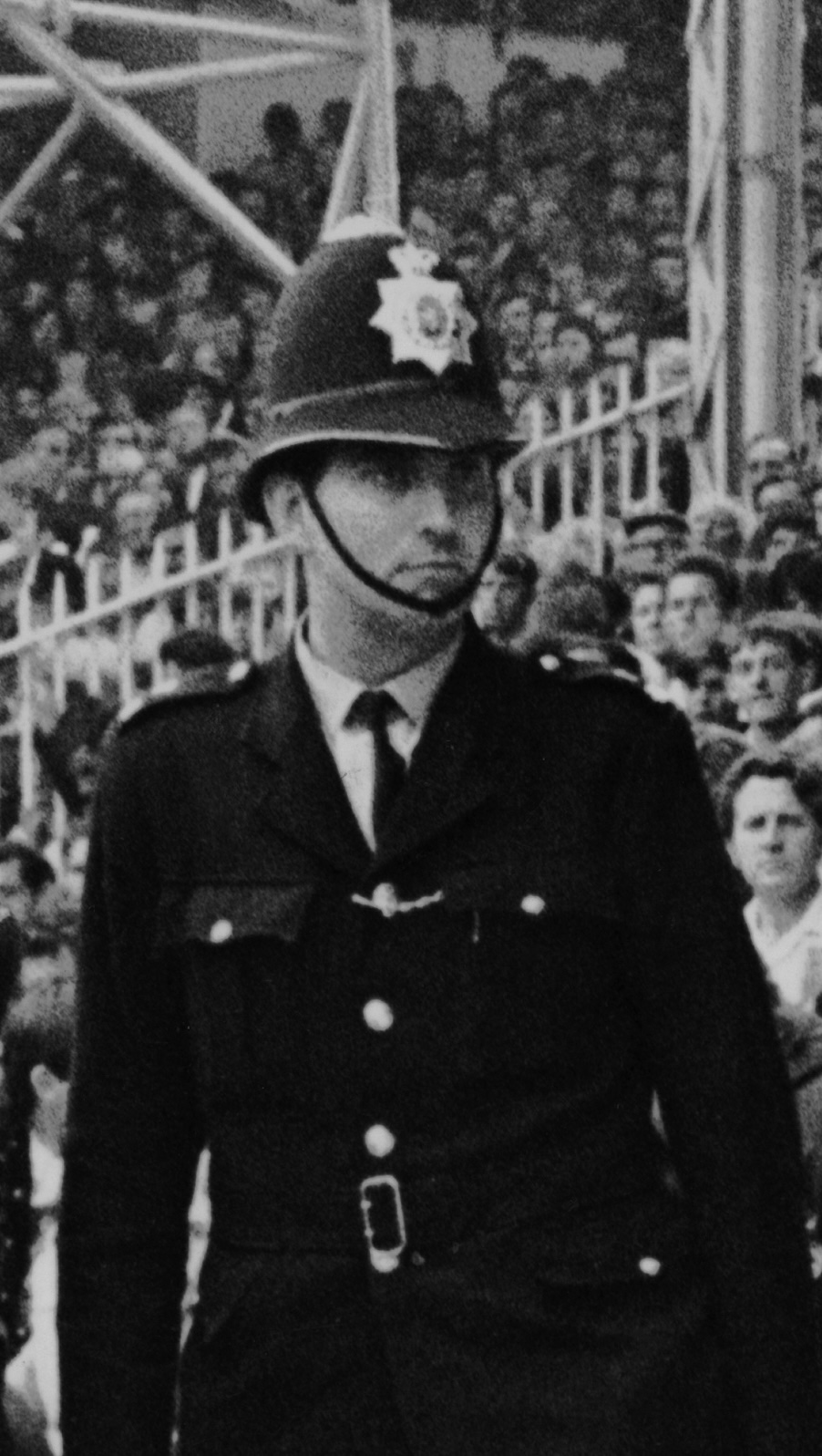

Armed London officers—a tiny portion of the total—quickly ended a terrorist attack on London Bridge in 2017.

Are other European police forces unarmed?

Generally, the European police are armed. But you have to put it against our firearms law. If you had a handgun under your bed in the UK and we heard about it, got a warrant and searched your house, you would go to prison, I believe for a minimum of five years. You might have no criminal history. We haven’t proved any criminal intent, but you’ve got illegal possession of a handgun and you’re going to get five years. That’s quite a big difference to other countries, especially the US.

In the UK, firearms are harder to obtain. That all but eliminates spur-of-the-moment actions, somebody getting shot over an insult in a bar. Here, firearms are used when they’re pre-planned. You and I have fallen out over some drug dealing business, so I go to a mate to acquire a firearm for the night to come around to your house and kill you and then I’ll get rid of it. By running surveillance against the more serious criminals, the UK police can often intervene when criminals are arranging to pick up firearms.

To the extent that respect is rooted in fear, doesn’t a sidearm engender respect?

I disagree with respect being synonymous with fear. If you only respect your parents because you’re scared stiff of them, that’s not great, is it? It may be true in the States that a firearm is needed to persuade anybody to do anything, but it’s not true in the UK. I’m not arguing for a UK model in the States. I’m simply saying that police officers here make thousands of arrests across the country every day without using firearms.

Police are equipped with things like tasers and with incapacitant spray in the UK, and those non-lethal options are used from time to time. But the degree of force required in this context is entirely different to the American context of a gun ownership culture that goes back hundreds of years.

My side would never suggest the States should disarm police, based on what I can see. I do think there’s a question about what proportionate arming looks like, and about giving the police the right weaponry and the right training to do the job.

From what I’ve seen, it’s not always proportionate in the States. Some of the equipment that was passed on to the US police after the Iraq War sends an odd message that the way to police our communities is with the same equipment that was used to deal with terrorist insurgents in a war overseas. That probably doesn’t help strike the right balance of trust and respect between communities and police.

“Our armed officers are trained to a far higher level than your average armed American cop because they can be, because it’s a small proportion. Ours are doing five weeks a year of training.“

How did the British system come about?

In Britain, in the 1700s, there were magistrates who were in charge of law and order in their parishes. Before the Industrial Revolution, all you had was parishes. To help them with a bit of muscle, they would swear in a local good chap as a constable. This was a very fragmented bottom-up model. After the Industrial Revolution and post the Napoleonic Wars, cities developed, and now you needed something more organized in places like London. It was Sir Robert Peel, the British Home Secretary, who founded the Metropolitan Police in 1829, and who lots of people would say is the founder of modern policing. Peel had this idea that you need to stick all these independent constables together into police forces which are called constabularies. They were very clear this wasn’t repressive, this wasn’t top-down, this wasn’t paramilitary. It was bottom-up community law enforcement. It was policing by consent of the public.

Along with the first commissioners of the Metropolitan Police, Peel drew up nine principles on what policing’s about. Bear in mind, this was nearly 200 years ago, and yet Peel’s Nine Principles of Policing remains the foundation of what is known around the world as community policing. One of the nine that occurs to me when we talk about an armed police force is Principle Four: “The degree of cooperation of the public that can be secured diminishes proportionately to the necessity of the use of physical force.”

If you want public support for policing, you need to think as much about maintaining the trust of the public as the weaponry you need to deal with dangerous individuals. You need to use the minimum amount of force. Then there’s Peel’s Principle Six: “Police use physical force to the extent necessary to secure observance of the law or to restore order only when the exercise of persuasion, advice and warning is found to be insufficient.”

What experiences in your career encapsulate the meaning of community policing?

I’ll give you two. The first came when I was chief constable of Surrey, a force of maybe 2,000 police officers and 1,500 unsworn staff. It’s a decent-sized department policing a million people in a commuter zone just on the edge of London, to give a sense of the place.

During the four years I was chief there, I put more resources into community policing. There was an annual survey of police work that gets done in the UK, and at the end of my period as chief there, the Surrey police had risen to have the highest level of trust of the public in the UK. That trust is a concrete asset. It helps the police get vital support and information from the public.

Now, flip forward a few years to when I’m running the national counter-terrorism machine. That work is partly about intelligence agencies doing sophisticated undercover operations. It’s partly about specialist armed resources dealing with really dangerous people. But it’s also about community policing. On my watch over four years, we stopped 27 attack plots, in some cases because of people in communities who trusted the police enough to say, “I don’t know if I’m worrying too much about this, but I thought you should know about X.” These calls were literally from the nosy neighbor. Or the relative suddenly worried about a family member who started behaving differently. It’s about trust. It’s about trust having a local police officer who knows their patch and who is known to all the shopkeepers and others. “Oh, that’s Mark. He’s in charge of this patch and he’s walking around regularly. You can trust him.”

Sir Robert Peel’s 9 Principles

UK policemen are called “bobbies” after Sir Robert Peel, who in 1829 formed the Metropolitan Police. He also twice served as Prime Minister.

- The basic mission for which the police exist is to prevent crime and disorder.

- The ability of the police to perform their duties is dependent upon public approval of police actions.

- Police must secure the willing cooperation of the public in voluntary observance of the law to be able to secure and maintain the respect of the public.

- The degree of cooperation of the public that can be secured diminishes proportionately to the necessity of the use of physical force.

- Police seek and preserve public favor not by catering to public opinion but by constantly demonstrating absolute impartial service to the law.

- Police use physical force to the extent necessary to secure observance of the law or to restore order only when the exercise of persuasion, advice and warning is found to be insufficient.

- Police, at all times, should maintain a relationship with the public that gives reality to the historic tradition that the police are the public and the public are the police; the police being only members of the public who are paid to give full-time attention to duties which are incumbent on every citizen in the interests of community welfare and existence.

- Police should always direct their action strictly toward their functions and never appear to usurp the powers of the judiciary.

- The test of police efficiency is the absence of crime and disorder, not the visible evidence of police action in dealing with it.

SOURCE: New Westminster Police

More from this issue

The WFH Issue

Most read from this issue

Above the Fray