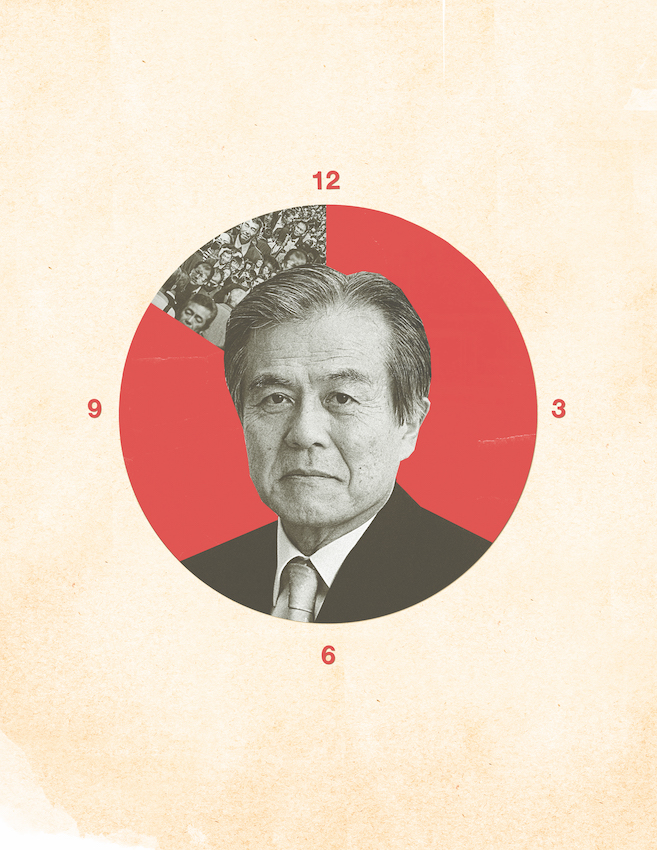

Mitsubishi Research Institute Chairman Hiroshi Komiyama says an aging workforce can be a catalyst for an economic evolutionary leap to a “Platinum Society.” Interview with Brunswick’s Daisuke Tsuchiya and Matthew Brown.

Download this article in Japanese.

In the 1960s, working as a chemical engineer, Hiroshi Komiyama became aware of the nascent environmental movement as a result of headlines surrounding severe pollution in Japan’s Dokai Bay. Later as a teacher and administrator, including a term as the 28th President of the University of Tokyo, he became directly involved in research and public policy and came to see that many of the problems surrounding sustainability lay with the design of social systems. These, he says, require a rethinking about the purpose of economic structures.

Today, as Chairman of the Mitsubishi Research Institute, Komiyama is a world-leading authority on global sustainability and the founder of a network of organizations pushing for change. In his books, includingBeyond the Limits to Growth: New Ideas for Sustainability from Japan, published in 2014, he writes about how the graying of society in China, South Korea and Germany poses an opportunity for innovation and individual well-being to spur a growing economy. Japan, with its high number of senior citizens, Komiyama says, can lead the way in promoting this trend.

In 2017, Komiyama spoke with Brunswick about his vision for what he calls a “Platinum Society,” the next step in the evolution of capitalism after the “golden age” of the 20th century. Far from being a drag on GDP, he believes older generations have an important role to play in keeping economies vital.

“We can create entire new industries and businesses,” Komiyama says. “I earnestly believe this will become the standard for a new society.”

Could you tell us how you define a Platinum Society and why it is needed?

A Platinum Society is a mature society with a focus not on volume growth, but on quality and a concern for how people live.

Capitalism as understood today is only for vigorous young people—but that cannot continue. The 20th century brought many discoveries in science and technology that directly supported social innovation. There is a correlation between scientific knowledge, technology and social change.

Today, the keywords are lifespan and saturation. Lifespan (or lifetime) consumption is nearing saturation. In developed countries, markets are saturated with products. In Japan, the US and Europe, the auto industry is more or less saturated at one car per every two people—people have to scrap one car to buy a new one. This is the basic reason why economic growth in developed nations is trending at incredibly low levels—saturation.

Population growth is also more or less at a point that is as high as it can go, so demand can’t increase. So the question is, how do we go about building our societies in an age of saturation? Extending the “golden age” practices of the 20th century won’t work. We need a new theory of industry. A Platinum Society would generate new industries through a qualitative expansion.

How do you see the older generation contributing to the economy?

First of all, people assume that the generations that contribute to labor productivity are those between the ages of 15 and 64. This is utter nonsense. The majority of people start to work at around the age of 20. The retirement age was based on life expectancy, which was about 60. The average life expectancy of Japanese people today is over 80.

I’m a good example. I’m 72—maybe a little weaker, but still active, and still vigorous intellectually. The idea that an aging society is synonymous with a deterioration in economic vitality is misguided.

According to Professor Hiroshi Yoshikawa’s popular bookMacroeconomics and the Japanese Economy, economic growth in Japan between 1955 and 1970 was 9.6% and growth in the working population was 1.3%—the difference of 8.3% is the growth of labor productivity. So most of the growth was attributable to innovation.

So the problem is not that the workforce is aging or decreasing, but whether or not innovation is taking place. Older people can be important drivers of innovation, as workers and as consumers.

How do you see seniors balancing leisure time with the urge to continue to work?

It depends on the individual. Some individuals still serve as CEO past the age of 80—but they are the exception. The profile of the “relaxed senior” applies to the majority. With information technology changing the shape of business so rapidly, it is hard for businesses at all levels to keep up. Relatively idle seniors, who only get paid about one-third of their normal salaries and have experience and time on their hands, can help fill those gaps.

There is no point in preserving the Earth if we are going to ignore how people live their lives.

Are there examples of companies where older workers are critical?

There are many. Mayekawa Manufacturing Company is a big maker of refrigeration systems that employs some 5,000 people. Mayekawa has a provisional retirement age set at 60, but workers can choose to stay with the company for as long as they want. One employee retired last year at 93. The oldest employee in the company now is 85.

Mayekawa is currently involved in a critical project at the damaged Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, supplying technology involved in the frozen wall in the soil to protect groundwater. It is the only company in the world capable of making a freezing machine such as the one they have deployed. The experience and expertise provided by senior staff was apparently indispensable in the development of this system.

Some companies are using recently retired professionals to teach the most recent skills to their workers. Scientific disciplines, for example, are evolving at an unprecedented pace—information science and robotics, as well as life sciences. Those skills are valuable.

What prompted you to develop your ideas about a Platinum Society?

I was in graduate school, working on a chemical engineering project—the petrochemical industry was booming. A ship anchored in an industrial area of the Dokai Bay in Kitakyushu had its propeller melt in the waters due to the high level of acidity caused by pollution. I was shocked; I wondered, “What kind of work am I involved in?”

The environmental movement was taking off right around that same time. Later, in the 1980s, talk of global warming emerged as I was getting more involved in the management of the University of Tokyo. We formed the Alliance for Global Sustainability between our university and the engineering schools of MIT [in the US] and ETH [in Switzerland] and with it, engaged in serious studies of global sustainability. Through that work, I came to realize that social systems themselves were the problem—not technology.

How does the economic model need to change?

We need to think in terms of society as a whole and on a global scale, and how that affects the individual lives that people are living. There is no point in preserving the Earth if we are going to ignore how people live their lives.

In the US, the conversation is growing about how we can live with capitalism in its current form. Japan has a lot to offer in that conversation. The concept of maximizing profits at all costs was not the basic idea here. For example, the motto of the Omi merchants [of the Edo period, 1603-1868] was “Good for the seller, good for the buyer, good for the community.” Japan’s capitalism has always stressed the need for benefits that are shared by everyone, and this is exactly what we are starting to hear in the US. Western investors complain that “return on equity” is low, but ROE is not the way we think in Japan.

What is the role of younger generations in those changes?

I mentioned earlier that saturation is one of the keywords, but freedom is another. Young people today are free. Back in the Edo period, 90% of Japanese were farmers. The average life expectancy was about 40. These people had no freedom in the sense of clothing, food, shelter, mobility or information.

Venture companies in Japan now are attracting new graduates for a low monthly salary of 200,000 yen [about $1,900]. These graduates are motivated by interesting work. International organizations attract doctors from renowned universities for the same sort of low pay. They take it because they are free—free from physical hardship and free to seek a sense of significance in their profession rather than financial gain. For those kinds of people, I would like to create social systems under which they would receive adequate compensation.

Hiroshi Komiyama

A scientist and former President of the University of Tokyo, Hiroshi Komiyama is the current Chairman of the Mitsubishi Research Institute, an organization focused on promoting sustainable business practices. He is the founder of the Platinum Network, a collective seeking socially aware economic structures, and the author of several books, includingBeyond the Limits to Growth: New Ideas for Sustainability from Japan(Springer, 2014).

Mitsubishi Research Instituteis a think tank and consultancy working with businesses and communities for sustainable development. It was launched by Mitsubishi Group in 1970, the centennial anniversary of the company’s founding.

To put a social value on businesses?

Yes. There are precedents. Take Mishima City as an example. During the era of industrialization, companies were using water from Mount Fuji to such an extent that water stopped flowing in the rivers running through the city. Wastewater was also being dumped into the rivers by residents, turning them into open sewers. As a result, the beautiful rivers in Mishima were in a terrible state. A nonprofit cleaned them out and companies began to treat the water and return it to the rivers. Fireflies have now come back to these clean-water places that are only 40 minutes away from Tokyo. The number of tourists dramatically expanded. As a result, there are now zero vacant stores in the entire city of Mishima. This is an example of an ecology movement helping restore the overall economy.

At present, the UN is working hard on a proposal for an Inclusive Wealth Index, which measures the social value of capital assets. There are other indicators that measure national happiness and the like. Typically, the only metric used to measure prosperity is GDP. There is no denying that GDP is significant, but we need to keep it in perspective.

In a Platinum Society, you see economies leveraging seniors and achieving economic growth through innovation?

That is correct. We should not give up on economic growth. We should not give up on struggling to end global warming. We also should not give up on the Inclusive Wealth Index. We should not give up on sustainable development goals. I truly believe mankind is on the verge of a historic turning point. And I believe it is right for Japan to take the lead.

What sectors do you see changing in particular?

The service sector, education sector and tourism. And more than anything else, health and products that support autonomy for seniors, before they enter nursing care. The health sector has a lot of potential for growth through innovation.

Has Japan made the most progress in this type of research to support autonomy?

Japan has an aging society, so it has naturally made progress in this research. Where we have been slow is in introducing the results into society.

Are there any countries doing this better?

The US seems more willing to try out new things and take action, and Germany and Sweden are notable for the degree of development of progressive aspects of their civil societies. The HAL wearable robotic system—a sophisticated therapy that helps people with paralysis learn to regain some mobility—was developed by Japanese researchers, but was more widely available in Europe. [See “Humanitarian Machines,” below.] It makes sense for Japanese researchers to team up with businesses and institutions in other countries to introduce these systems into society.

The HAL system could make a single caregiver in a nursing facility able to take care of many more people. That’s one way that GDP can rise as a result of the elderly being considered through the lenses of innovation. Nursing care could develop the way the auto industry did when Henry Ford cut production time by 90% and prices by 70%.

What other sorts of goods and services are seniors looking for?

Experiences like cruises and museums visits—these are crowded with older people. Demand for new cars declines among the elderly, but it expands for products and services that enhance their lifestyles and quality of life. And it can continue to grow. Innovation will surely play an extremely important role and Japan is the country that can do it.

Humanitarian Machines

Developed by Japanese researchers, the Hybrid Assisted Limb, or HAL, is a therapeutic wearable robotic system that obeys electrical impulses from the wearer’s brain. The signals arethe same as those used to trigger muscle movement, so wearers can activate the device just by thinking about it, as they would their own limbs. A positive feedback loop to the patient’s brain makes it possible for people who have suffered paralysis as the result of injury to learn to move the affected limbs unassisted.

Dr. Yoshiyuki Sankai of the University of Tsukuba founded Cyberdyne in 2004 to create robotic “exoskeleton” systems. Rather than the autonomous walking and talking robots of popular imagination, Cyberdyne’s devices are purely assistive, aiding and strengthening the movements of the wearers. One of the applications for the full-body version would allow healthcare workers in assisted living facilities and hospitals to more easily lift patients. The technology is also being used to assist workers in other physically demanding roles, such as disaster relief and construction.

More from this issue

The Japan Issue

Most read from this issue

Activism Alert