San Francisco Conservatory of Music’s President David Stull has a vision for music education in the 21st century—beginning with a new building. By Carlton Wilkinson.

San Francisco’s Civic Center is a large triangle of a dozen city blocks featuring landmark architecture around the historic City Hall building with its gold-leafed dome. Inside the district’s 300-plus acres are the Davies Symphony Hall, the War Memorial Opera House, the Asian Art Museum and the SF Jazz Center—all national and international magnets of culture.

In that district’s heart is where you now find the San Francisco Conservatory of Music’s Bowes Center, a brand new 170,000 square-foot vertical campus located across the street from the Davies Symphony Hall, featuring classrooms, residencies, dining halls, performance and rehearsal spaces, technology labs, offices, a professional recording studio and a radio station. Glass at its street level emphasizes the symbolism of the building as a transparent conduit between the three worlds of academia, community and professional performance.

The entire building, in fact, is part of a vision for the conservatory’s identity that involves fluid relationships between communities and lectures halls, students and professionals, inside and outside. David Stull, the institution’s President since 2013, is the man behind that vision. Under his leadership, SFCM bought an important artist management company, Opus 3, representing professional classical, jazz and world music artists—a move without clear precedent for a music institution and a rare instance of a non-profit buying a for-profit company.

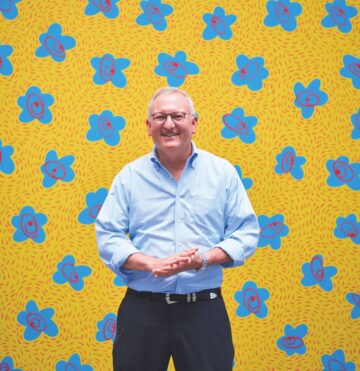

The exterior of the Bowes Center is a striking addition to the Civic Center.

In addition to its new professional recording studio, the school also recently purchased its own record label, headquartered in the Netherlands. And its Technology and Applied Composition program, or TAC, is a state-of the-art laboratory for students to access training and expertise in music creation and sound for all digital media, including film and video games.

“They’re standing right next to the crucible in which the fire of tomorrow’s music is burning,” Stull says. “If you really want to inspire a student, put them next to that level of innovation.”

The goal, Stull told theBrunswick Reviewin an interview in April, is to create an apprenticeship experience for the conservatory’s students, while simultaneously giving them broader exposure to the world of ideas and instilling in them a sense of community responsibility. That, in turn, will benefit the city community that is home to the school and also, hopefully, make the world in general a better place.

At the 2022 Grammy Awards, artists represented by the school’s Opus 3 snagged several honors, including top names Bela Fleck, Yo-Yo Ma, Emanuel Ax, Jennifer Koh and Chanticleer. And Rogét Chahayed, a now famous SFCM producer and songwriter alumnus, won his first Grammy for his work with Doja Cat and SZA. Chahayed had also been nominated for Producer of the Year.

More recently, the school benefited from the announcement of a forthcoming grant from another famous alum, Gordon Getty. Getty is auctioning an art collection estimated to be worth more than $180 million and dividing up the proceeds among arts and sciences institutions of the Bay area. In a response published in theSan Francisco Chronicle, Stull called the gift “a profound investment in our work” and “a call to action” for a brighter future.

Stull was formerly a professional tuba player with the American Brass Quintet, Live at Lincoln Center and other ensembles. He later became a professor and then Dean of his alma mater, Oberlin Conservatory. There, he oversaw the $20 million construction of the Kohl Building, a 40,000 square feet facility including a recording studio. The experience required significant fund-raising, planning and community building, skills that helped prepare him for the far more extensive Bowes Center project at SFCM.

Long before he took over, the San Francisco Conservatory of Music already had a reputation as a small, respectable music training program. Founded in 1917, its alumni roster includes composer John Adams and violinists Yehudi Menuhin and Isaac Stern.

“I had a series of ideas of what the modern conservatory should be. And that it actually shouldn’t just be limited to a ‘conservatory’ anymore.”

“It was a place where people felt welcomed,” Stull says. “It created a bit of a culture of being able to do things that hadn’t been done. It was fertile ground for new ideas.”

In 2006, the school began a push for a higher profile that saw it relocating to a new building at 50 Oak Street, on the perimeter of the Civic Center district. When Stull started in 2013, his job was to push toward the goal of making the one-of-a-kind conservatory into a world-leading, 21st century institution. But he also wanted to redefine music education.

“I had a series of ideas of what the modern conservatory should be,” President Stull says. “And that it actually shouldn’t just be limited to a ‘conservatory’ anymore.”

He wanted to put the school closer to the cultural action of Civic Center with a presence that would physically represent the innovation he had in mind. The result is the $200 million-plus Ute and William K. Bowes, Jr. Center for Performing Arts, an ambitious achievement of form married to function. Inaugurated in November of 2021, it had its public opening in March of 2022.

Stull is also a pilot, has been for 30 years, and has flown across the country many times, an experience he credits for helping him keep a fresh outlook on his work.

“The thing about flying is that it’s one of the few spaces in the world where you have to be truly present in the moment,” he says. “It also forces you to let go of your own delusion of space. And you start seeing the world very differently.”

What were some of the challenges you faced getting the new building project off the ground?

We had a very ambitious vision, not just for housing for our students, but housing the residents who are on site. We had 27 low-income families that we wanted to house on site because we were tearing a building down that currently housed them. We wanted to be able to have these world-class boutique recital halls, but loaded with glass. Transparency was the theme of the building: How do we bring music into the community, and allow it to flow back and forth? How do we make sure, when you’re in the hall, it’s recognizable as San Francisco?

In one of the initial conversations with the city, they were concerned about how much glass we had at the street level, the transparency. There are quite wonderful buildings around us—the War Memorial Opera House, which is Romanesque, set back, high columns, really beautifully articulated; and Davies Hall is kind of an ’80s modern concrete building stepped back off of the street by 30 feet, concrete all around the bottom and glass above. From the street level, very much like a fortress. We wanted a completely opposite view.

The message we’re sending is about the importance of art and the relationship of art to this community. We want to be transparent, so we argued that our building should pressurize that agenda, not be victim to it. Architecture shapes experience.

The finished building is highly transparent at the ground level. There’s actually a recital hall downstairs that welcomes people in visually. When you’re acoustically in the space, it’s absolutely silent. And then this gorgeous capstone space upstairs. From the penthouse hall, you can see the dome of City Hall and, farther away, the Transamerica Pyramid. The light in San Francisco changes in these beautiful ways because the city is adjacent to the Pacific.

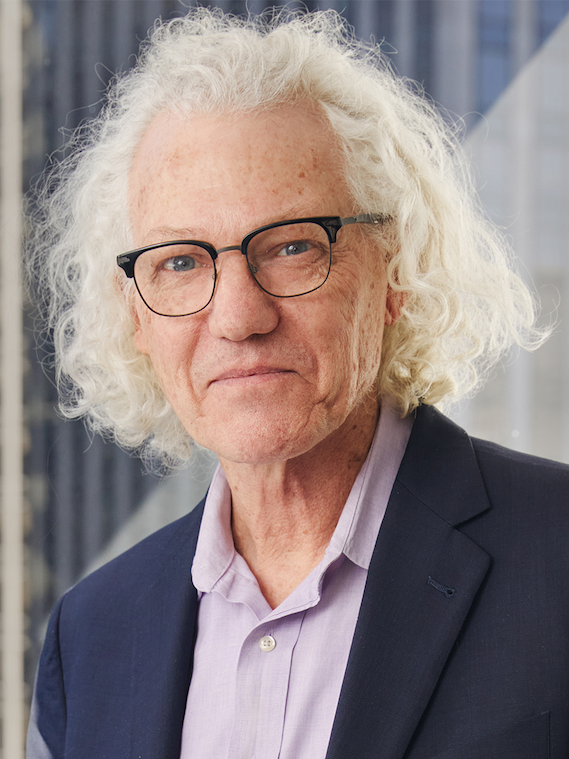

San Francisco Conservatory of Music President David Stull.

That fluid relationship of the conservatory and its surroundings also relates to SFCM’s mission of bridging academic and professional life. Can you talk about that?

Conservatory education has been perceived as vocational—almost like we’re training people to fix air conditioners. That’s not what we do. Our students are technically tremendously proficient. But the exploration of becoming an artist is something very different than that. It’s an intellectual exercise, it’s a physical exercise, it’s a spiritual exercise, and it’s a professional exercise. So, we have these four pillars of the curriculum: the artist, the intellectual, the professional, the individual.

Music tends to bring people together. It tends to unite them. For children, it dramatically changes their development. Not just their intellectual capacity, but their social development: They have to listen together, work together, play together. If we were to stare at the world today, we’d recognize these skills of empathy and listening and collaboration are under attack. They’re being lost to us. It’s very difficult to suggest that science could solve the problems of global warming, for instance, in the absence of a social agenda that would support that activity. So the whole concept of the building reaching into a community is just an extension of what our philosophy is—art is about community; art is about expressing the best version of ourselves.

To become a highly successful artist, to even win an orchestra job, they have to be interesting musicians. Not just technically highly proficient. They have to be able to tell a story and understand a story in the music. And they’ll have some experience of working with people in communities who may have struggled with questions themselves. They know what that means, from a humanistic level, to do that. It’s a very different path than the purely vocational one of, “Practice your scales 10 hours a day.”

So, yes, our approach results in a very strong vocational connection. But that is a derivative of a broader vision of what can be achieved through education.

How does the Bowes Center help you do that?

The Bowes Center became a focus and a fusion of curricular ambition. I had those four pillars of the curriculum in mind—artist, intellectual, professional, individual. And I had two very specific programs I wanted to launch. One was in technology—preparing classically trained composers to score for games and for film, and to undertake sound design and engineering. The center of all that professional work was happening on the West Coast. Why would you not be harnessing the top producers and composers, who live right here, work here, to be the mentors, and consequently the pipeline then, into this opportunity?

I knew that I was very interested in starting a Roots, Jazz and American Music program that was also different, based more around a focus on improvisation and the creation in the traditions of jazz, rather than many programs than kind of treat it now as a classical art form, and so almost limit themselves to jazz masters, if you will.

So I had those two curriculum directions. Looking at the situation at the SFCM at the time, I immediately said, Well, look, you all know that you need a residence hall. But I would suggest you need more than that. You need a flag in the ground: 50 Oak Street is a beautiful building, but let’s try and be right at the Civic Center, rather than off to the side. Let’s raise the money for the building, so it becomes an asset class in the endowment. If students then pay for housing, that money can flow back to scholarships. It’s a way to rope in both people who want to invest in capital projects and scholarship donors to the same model.

And then let’s think about how the building would support the broader agenda: buying a management company; developing this seamless professional/student relationship, this real apprentice model that we should have. How does the building energize those mission points?

“I see this as central to addressing the world’s problems, and not ancillary to it.”

This sounds more like a business proposal rather than a philanthropic project.

Yes, but that’s also why it was so successful philanthropically. What philanthropists rarely get from the nonprofit world is, “This is a business model: It’s how your investment will transform what we do at our institution and do this much good in the community.” So we actually treated the Bowes Center, from the standpoint of a fundraising model, as an ROI. We’ll steward your resources in such a way as to give you that return. It’s much like how a hedge fund manager might pitch return, conjoined with someone who’s mission driven.

There’s been so much divisiveness in the US in recent years. Are those concerns part of the equation behind the school’s work?

Absolutely. If we’re not in the thick of the central challenges we face to our humanity, then we’re not doing our job as artists, creators, whether that’s working as teachers or performers or just advocates.

When we arrived at the threshold of Black Lives Matter, we had already been investing in a program at the historic Third Baptist Church, a wonderful collaboration between Temple Emmanuel, the wealthiest synagogue in the city; the Third Baptist Church, which is not as well-funded; the District Board of Supervisors; the Interfaith Council; us; and the Koret Foundation. All of those came together to start this program for children. We gave them free music lessons and it was combined with after school homework help. Yamaha donated the instruments for that program.

So with Black Lives Matter, we were able to build on some of that energy, and we started asking ourselves, how could we change the curriculum, change a program, change opportunity, to try and actually set forth lasting metamorphosis, relative to the inclusion of all people within our country in the experience of music?

That resulted in several initiatives, one of which was our Emerging Black Composers Project. Instead of saying, “Let’s commission a Black composer for one year,” it’s 10 years. We got the San Francisco Symphony involved. That spread out into how we thought about the programming of our concert series.

We also have an international community—40% of our students are not American. The history of race in America is something those students know only as an abstract concept. But they may have to deal with a whole range of other issues: What is it to grow up in a Communist regime, where if I wanted to write a song about my distaste for the leadership of my country, I could find myself in prison as an artist?

We have a number of artists from Russia. They’ve never been associated with Vladimir Putin, but they were expected to denounce Putin. Meanwhile they have people visiting their families in Russia saying, “Your son or daughter better not say anything against President Putin. And, oh, by the way, if they do, it’s now a 15-year jail term if they come back to Russia.” We’ve tried to stay in front of that. These individuals are victims of tyranny as much as anybody else.

So you see your role in part in a societal context?

I see this as central to addressing the world’s problems, and not ancillary to it. When I look at the future—how we deal with social division, geopolitical strife, climate change, the rise of CRISPR [gene-editing] technology, artificial intelligence, quantum computing—I suppose I see a convergence of these things coming, technology that could, in many respects, save our bacon, but also systems of government and human communication which are destined to defeat those solutions. No matter how quickly science is advancing, and even though it may reveal solutions to us about the challenges we face as a species, are we going to have the tools necessary among ourselves to make good decisions?

So I come back again to where I began, which is empathy, communication, community, trust, listening: All these things are engendered through music. It’s really important for kids to have that experience so they can retain those skills intrinsically.

More from this issue

Acceleration

Most read from this issue

Virgil Abloh