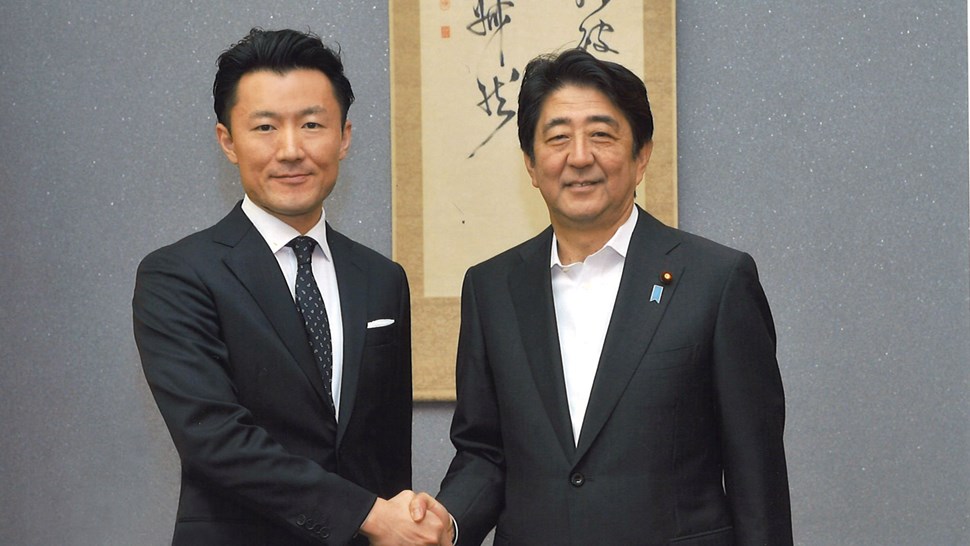

In fall of 2020, Brunswick’s Yoichiro Sato, a former member of Prime Minister Shinzō Abe's office, offered his insights into the outgoing prime minister’s power and how his policies could fare under the new Suga administration. By Daisuke Tsuchiya.

On September 16, 2020, Shinzō Abe ended his tenure and lefthis office as Prime Minister of Japan, the world’s third-largest national economy and a key ally and trade partner with the US, Asia and Europe. Abe was the longest-serving prime minister in Japan’s history, holding the office from 2006 to 2007 and again from 2012 to 2020. During that time, he set the tone for the country’s politics, economy and foreign trade. Policies of monetary easing and fiscal stimulus to jumpstart the economy, and regulatory reforms that emphasized transparency intended to open Japan to foreign investors, were so closely identified with the Prime Minister that they continue to bear his name: Abenomics.

On the same day, self-made career politician Yoshihide Suga, who was the right arm for Abe as Chief Cabinet Secretary during the Abe administration, was elected as the 99th prime minister of Japan, taking over as the nation is addressing another severe economic blow from the global COVID-19 pandemic.

Suga’s top priority is to strike a balance between advancing economic growth and maintaining health safety measures that forced the postponement of the 2020 Tokyo Olympic games, which were rescheduled and held in July of 2021.

Japan, home to over 3,000 of the world’s 5,000 oldest companies, is a tough market for anyone to launch a new business, a fact that Brunswick Partners Daisuke Tsuchiya and Yoichiro Sato know well. Both are veterans of government work in Abe’s administration. As advisor on foreign affairs, Yoichiro worked directly with both Abe and Suga. Shortly after Abe stepped down in September of 2020, Daisuke interviewed Yoichiro about the challenges as well as the opportunities of the Japanese market, and what the change in government meant for business.

What do you think are the main achievements of Prime Minister Abe’s administration?

In a nutshell, I think the prime minister was successful in fostering hope for Japan, for the people of Japan. He was very, very good at changing the narrative for the country. He made the people of Japan feel more confident about the future. His focus was revitalizing the Japanese economy—his administration started in 2012, just after the Great East Japan Earthquake. We didn’t have a lot of hope for the future then. We had spent almost two decades in economic stagnation and price deflation. So Abenomics aimed to push national growth through easing monetary policy, boosting fiscal stimulus and pushing structural reform.

The administration put in place reforms or measures to facilitate dialogue between Japanese corporations and investors, that is, the governance code and stewardship code. The aim was to make the market more attractive for both domestic and international investors and by doing so, to incentivize Japanese corporates to create greater value through their businesses as well as to achieve share prices that more closely reflect their value. They’re now more expected to share and disclose their information. The government also pushed Japanese corporates to enhance governance and increase productivity. This includes work-related reforms and promoting diversity with female empowerment. Such measures had not been undertaken with the same rigor by previous administrations due to strong opposition from vested interest groups, even parliament members or ministries within the government. In the economy, the unemployment rate dropped from around 4.3% to 2.4%, which produced over four million new hirings, and the employment of women dramatically increased.

Career civil service is at the core of Japanese government. Lifetime civil servants continue to enjoy strong respect and are at the heart of a lot of long-term policy development. Were Abe’s accomplishments a factor of his personality or a sign of a shift in underlying, institutional trends for the long term?

I think that’s a great point. Prime Minister Abe’s administration is one of the most powerful in the history of Japan as a democratic country. During his second term, seven and half years in office, he won six times through the national election, either in the lower house or upper house. The Abe administration also managed to establish the agency for human resources—the Cabinet Bureau of Personnel Affairs—in order to have more influence over personnel decisions, especially of senior civil servants. The robust policies of reform pushed forward by Abe’s administration are definitely a result of more coordination among key ministries, thanks to the political capital that he had, and the increased political power over the civil service.

However, there is also a more underlying sense of urgency in all areas of government to revitalize the economy, given international competition and a fast-aging population. Without that, the Japanese ministries and government agencies that have such an important role to play in realizing long-term policy change in Japan would not have been mobilized as effectively as they were. I feel this is a trend that will continue under Prime Minister Suga and subsequent administrations.

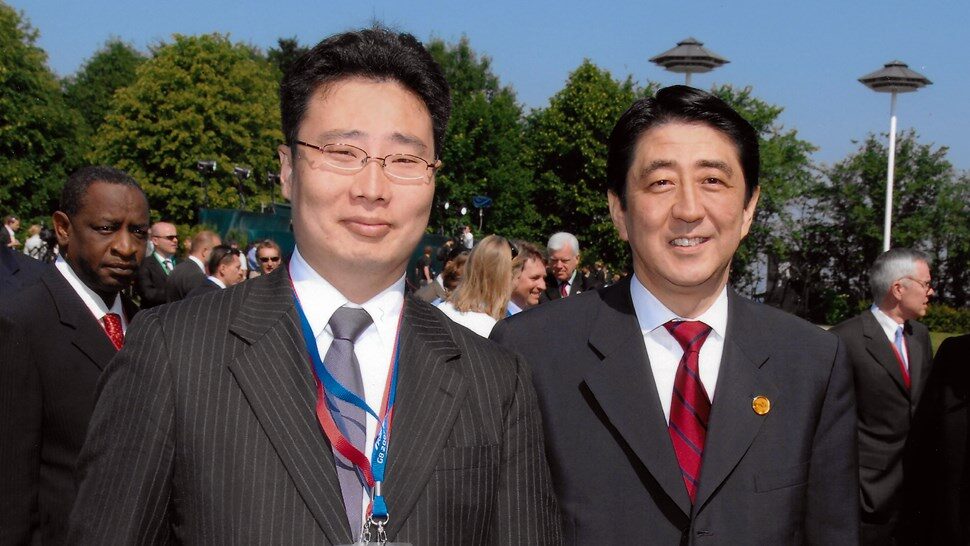

Brunswick Partner Daisuke Tsuchiya knew Prime Minister Shinzo Abe personally during his first tenure as Prime Minister in 2006-2007 and acted as his interpreter on occasions such as the G8 Summit, pictured here.

With the changes in the governance code and the stewardship code, more foreign investors are buying shares of Japanese companies. Activist shareholders are also more engaged, as a result of Abe’s encouragement for more dialogue with shareholders. Do you see that trend continuing?

Yes. I think it’s a long-term trend, a fundamental vector. The ruling parties—LDP and the alliance with Komeito—want to push the national economy, leveraging foreign investment and welcoming more people from the rest of the world. That’s been one of the key elements of Abenomics, and they want to push harder.

The current focus is to address the COVID-19 situation, where they have to strike a balance between economic growth and public health. But in the long term, once we’ve recovered, they want to celebrate the Olympics and to welcome more people and visitors through various measures. The government has relaxed the restrictions on immigrants or professional workers from other parts of the world, for instance. Tourism was on an astronomical rise in the last decade before the pandemic started. I think the new administration will have the support to continue policies to connect Japan and other markets.

Foreign direct investment as a percentage of GDP, even as it has increased, is still very low in Japan, putting Japan at around 29th in the world, despite all of the measures that Abe has undertaken. What do you think are the challenges for foreign businesses to enter Japan?

That’s one of the most important questions we have to ask ourselves. One initiative taken by the Tokyo municipal government is to establish and brand the city as a new Asian regional hub for finance, to attract more and more investors or fund managers on the ground in Tokyo. They have discussed a variety of these challenges for international corporates or financial institutions working in Tokyo or in Japan—taxation, language issues, complexity of regulations, and others. They understand that without cooperation by the national government and the business sectors they cannot achieve high-level investment and will struggle to encourage global businesses to be on the ground in Japan.

However there is only so much that national and local government initiatives can achieve. There will be work required on the side of foreign businesses as well, to crack the Japanese market which, as data shows, is not an easy market to succeed in.

Yes, it is not an easy market—not only for new foreign businesses. What practical steps should foreign businesses be taking to establish themselves in Japan?

First, they should try to have a good understanding of the Japanese market. I’m not saying the Japanese market is very unique. We do have many things in common with other markets of the world. But there are cultural and regulatory differences, and generally a much longer period required for establishing credibility. Showing that you understand those differences would be a good signal in marketing and branding.

Second, I would suggest foreign companies make the effort to engage stakeholders in the local market for the long term. Regulatory matters or some differences in rules or commercial practices across industries—those might pose challenges for international corporates who want to disrupt or enter a new market here. But without having a good level of trust with some key Japanese stakeholders—government, regulators, trade associations, consumers, business suppliers or media outlets—I don’t think anyone could be successful in the long term.

“Without having a good level of trust with some key Japanese stakeholders … I don’t think anyone could be successful in the long term.“

That’s an interesting point. Stakeholder capitalism has been all the rage globally in the last couple of years. Japan has been doing this for a few centuries. The Omi Shonin (Omi merchants) had the concept of “Sanpo Yoshi” or “three ways good”—business has to be good for the buyer, seller and for society. So you’re saying, understanding that mindset is needed to succeed in business in Japan?

Yes. I think not only in Japan but also in the global market, multi-stakeholder engagement is a powerful way to stand out these days. But absolutely the case is true in Japan—an old and yet a new trend. I believe it’s in the DNA of Japanese business and Japanese society.

You worked with Suga’s team when he was Chief Cabinet Secretary. What insights do you have into what sort of prime minister he will be?

Suga has been a very important key player in the cabinet as a very close partner for Prime Minister Abe, especially around coordinating with key ministries. When the government planned reforms or new initiatives, they needed strong support from key ministries such as taxation or education or labor reform or anything. Suga has been vocal in promoting the key initiatives that push the national economy, including relaxing visas for visitors and restrictions on professional workers.

Suga also strongly supported an initiative in taxation, what we call “Furusato Nozei,” a policy aiming to revitalize regional economies by allowing tax-deductible donations to municipalities. He comes from a rural background as well, so decentralization and revitalizing regions in Japan is an important theme for him.

Suga really understands the importance of leveraging the global economy for Japan’s benefit. He was a strong supporter for promoting and exporting Japanese agriculture products to other parts of the world, a key mindset change, as traditionally Japanese agriculture has not been export-orientated. One common theme that runs through all of this is, he has been very focused on revitalizing the Japanese regional economy through attracting foreign investment and people. Consistency is key. Some analysts are already saying that “Suganomics” will take over from Abenomics.

In terms of geopolitics, I think the main thing on the minds of many is the US-China relationship. How do you see that affecting Japanese businesses abroad and non-Japanese businesses interested in Japan?

Yes, the general geopolitical tension affects Japanese politics as well as the Japanese economy and business environment. Aligned with the security measures or political measures taken by the US or other countries, the Japanese government has implemented restrictions or new rules around trade with foreign countries.

Japanese corporations have been affected by a decrease in trade volume with China, while seeking more partners in South East Asian countries. However, Japanese corporates really understand the importance of keeping business ties with China, and hence the key going forward will be whether some perceived security concerns can be addressed and whether trust in China and Chinese companies can be improved.

In terms of regional or international security, Suga will likely take over the course charted by Abe and emphasize the US-Japan alliance and partnership with India, Australia, as well as important relationships with China and other Asian countries in order to secure this region.

More from this issue

The WFH Issue

Most read from this issue

Race Against Time