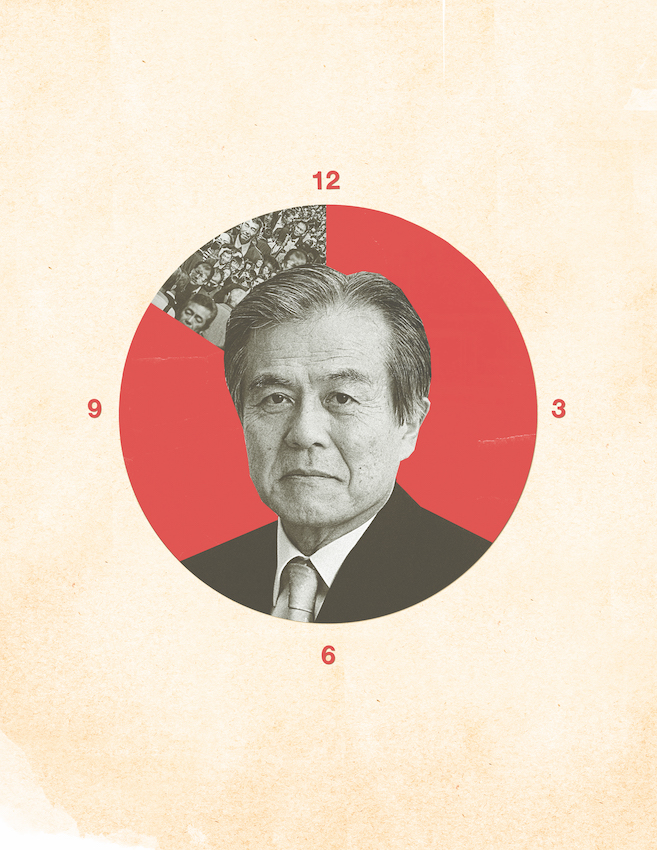

In 2016, Osamu Nagayama was leader of the board of Chugai and Sony. He talked to Brunswick’s Daisuke Tsuchiya

Download the article in Japanese

When we spoke to Osamu Nagayama in 2016, he was dividing his time between pharmaceutical company Chugai, where he held both the CEO and Chairman posts, and electronics giant Sony, where he was an independent director and Chairman of the board.

In an interview in a conference room in Chugai’s Tokyo headquarters, he noted that while the two businesses are very different, the responsibilities of their boards are the same, making the transfer of his skills from one to the other a natural step. In addition, working with the leadership of the two companies has allowed him to enhance his own experience and expertise, to the benefit of both businesses.

Sony and Chugai are both international companies and have governance structures that require external directors on their boards. Traditionally however, Japanese boards have been almost exclusively comprised of executives and insiders. Nagayama sees that changing quickly, despite cultural resistance, spurred in part by governance reforms instituted by Prime Minister Shinzō Abe’s administration.

Contrary to what most people might think, Nagayama said the main function of a board is not to make money for the company. Instead, it is to create transparency. The relationship between the board and executive management provides an important set of “checks and balances” to the benefit of all stakeholders, including shareholders.

In light of the board’s oversight function, Nagayama made the case that the CEO and chairman should be on good terms, but says a close friendship is “dangerous.”

Being CEO and Chairman of Chugai is a very demanding position. What led you to also take on the Chairman role at Sony?

I joined Sony’s board in 2010 and was appointed its Chairman in 2013. The management and Yotaro Kobayashi, Chairman at the time, invited me to consider the post. Because Sony is quite a large, diverse, globalized company, I instantly thought about the challenges I would face, being a board member. I knew I had a perspective to bring—life experience and business knowledge. I also thought that being on the Sony board might benefit Chugai, providing insight into ways to improve its management and governance. I was a little hesitant, but in the end, after some consideration, I accepted.

I have also been a fan of Sony for a long time. Over the years I have loved products such as the Walkman and its digital cameras. I had a Trinitron TV, for instance, and still use my Sony DVD/Blu-ray player. To be fair, I think it would be hard to find Japanese people who have not used Sony products. The company is somewhat iconic here. Some of the products, such as the Walkman, helped define parts of popular culture worldwide.

“… Changes in Japan are happening all of a sudden—demand for external directors is growing but the pool of candidates is still limited.”

Coming from the pharmaceutical business at Chugai, were there any big surprises when you got to Sony?

The biggest surprise was how closely scrutinized it is. Sony’s businesses cover everything from electronics to entertainment to financing and insurance—and the company is all very consumer focused.

Any company action, any issue about Sony, attracts huge amounts of public attention. That doesn’t happen at Chugai, where our customers are mostly medical professionals.

That was a big surprise, but in fact, it helped me at Chugai. We now spend more time looking beyond our professional customers for ways that our products impact the users. As a result of my Sony experience, we are more sensitive to the needs of those who see the benefit of our products—to patients and society.

In other ways, too, being on the board of Sony has broadened my perspective, particularly in the way global operations are run. Chugai is much smaller, but our drugs are designed for the whole world.

Do you feel pressure to prioritize shareholders’ interests over other stakeholders, such as customers or workers?

When people talk about shareholder interest, usually they are really talking about profitability and increasing the stock price in the short term. Long-term shareholders, on the other hand, expect there will be some ups and downs, trusting that the company will grow soundly over time.

My experience tells me that no global company can make a short-term profit unless it also invests in the long-term future. On the other hand, many companies might keep a losing division because it represents the future of the business. That’s fine for losses of two or three years, but not more than that. Saying that you are investing for the future doesn’t allow you to go on losing money each year.

Some business leaders of large companies, such as GE, primarily think about the long-term future. But, of course, they never forget to satisfy shareholders and stakeholders through dividends or increasing the value of the company.

So you don’t have to choose short-term or long-term success. You have to achieve those in tandem.

“The role of an external board member is not to coach the management to make more money or succeed in the business, but to check what management has promised to achieve.”

In Japan, traditionally only a small group of listed companies have had multiple external directors. The new governance code recommends each board has two or more. Is that a positive move?

Who can say what is right in this case? It is a challenge but it is promoted vigorously by Prime Minister Abe’s administration. These changes in Japan are happening all of a sudden—demand for external directors is growing but the pool of candidates is still limited.

The reality is that the domestic market is shrinking. As businesses look to expand overseas, they have to adapt to the cultures or requirements of those countries. Putting two outsiders on the board is a first step toward internationally accepted governance where external board members are a key element.

Now, whether it’s better to have more external board members or more executive board members—that depends on the organization. There is no one-size-fits-all solution. Sony has 10 external directors out of a board of 12, but that fits with its diverse international agenda.

So, we should not be too dogmatic about the style of corporate governance. Certainly for Sony, which is running a diverse business, it is better to have the experience of people in different industries or with different viewpoints

No matter how many external directors a board has, its role is to look after the interests of all stakeholders and ensure the necessary transparency of management.

Do you feel some companies would be better off without adding external directors?

Japanese business has been reliant on this internal board style for so many years. I don’t see anything particularly wrong with that, but the business environment is changing quite rapidly. With a greater supply of potential directors and with more time, I think we will see companies moving toward more external directors.

Right now though, a lot of people are still skeptical about the role of external board members—not just people in Japan but outsiders as well. As a CEO, I might think, why do I want a board member who doesn’t know about my business? But that misunderstands the role of the board, which is really to judge management’s effectiveness. It’s about ensuring transparency. That is something external directors can do very well.

What do you think makes a good external director? What do you look for?

It’s not like a university test, where if you score so many points on each item, you pass. In general, you need someone with experience managing a business and someone who knows what transparency is. The role of an external board member is not to coach the management to make more money or succeed in the business, but to check what management has promised to achieve and to consider whether they are doing it right.

Osamu Nagayama

At the time of this interview, Osamu Nagayama served as Chairman and CEO of Chugai Pharmaceutical. He led Chugai in the establishment of a strategic alliance with Roche in 2001 and now manages Chugai as a Roche Group unit. Since 2006, he was a member of the Enlarged Corporate Executive Committee of Roche as well. He became a member of the board of directors at Sony since 2010, and was appointed to the Chairman position in 2013.

Chugai Pharmaceutical

One of Japan’s leading research-based pharmaceutical companies with a focus on biotech, Chugai was founded in 1925. It specializes in prescription drugs and is one of the sector’s largest companies on the Tokyo Stock Exchange. As a member of the Roche Group, Chugai is involved in research and development activities in Japan and abroad.

Sony

Founded in 1946, Sony has grown into a leading global maker of electronic equipment and software for consumer and professional markets. Its businesses include mobile communications, game and network services, imaging products, entertainment and financial services. Sony is headquartered in Tokyo, Japan.

Even in a company like Sony, there are still relatively few women and few foreigners on the boards. Do you see that changing?

As companies adopt the new governance code, they will realize they need to have a more diverse board. Some large companies are already recruiting more outside and non-Japanese board members. The opinions of non-Japanese directors can be very different and that’s valuable.

Women are coming to executive and board positions, but a little slower than in the West. There is not yet a critical mass of women eligible for those roles and Japanese companies have only recently begun to recruit and train them. As a result, the numbers are growing rapidly and more women are gaining experience. It’s only a matter of time before they come up through the ranks.

In light of the board’s checks-and-balances relationship with management, should a board with external directors be involved in forming specific business strategy?

That’s a challenging question for any outside board member to answer. Our primary mission is to judge whether management is serving the best interests of all the stakeholders. For business matters, internal directors will typically know better.

Sony has gone through a little turbulence in the last couple of years and had a very difficult time with some poor financial performance—we’re making a recovery now. As outside board members of this diverse company, we had to think a lot about whether each business was worth keepingor whether we should get out of it.

Sometimes we had to demand enough material information for us to judge. In those moments, when a critical decision is required, there’s no way to draw a clear line or to say board members should or shouldn’t be getting deeply involved in the business. So it’s a difficult question. We just have to try to do what’s best for stakeholders in each case.

At Chugai, you serve as both Chairman and CEO. At Sony they are separate roles. Ideally, should they be split?

If the chairman has good management and transparency in mind, then it doesn’t really matter whether he is an outsider or an executive. In a critical period, stakeholders might demand more transparency and objective judgment. In those cases, the chairman might have to be an outside board member.

When the roles are split, it’s very important that there is a spirit of cooperation between management and outside board members. But that should not be translated into a close friendship necessarily. That can be dangerous. Boards have to make judgments—cooperation with management has to translate into objective conclusions.

A board of outside members may even have to dismiss the management. That’s an extreme example of the board’s function. Our mission is to help improve the running of the company.

On the other hand, I think you can push it too much, keep the CEO at too much of a distance—you could wind up making a wrong judgment. That’s dangerous too.

More from this issue

The Japan Issue

Most read from this issue

Capitalism: A Coming of Age Story