During his 2012 re-election effort, President Barack Obama criticized his GOP opponent, Mitt Romney, over his career in private equity, an investment strategy popularly known for breaking up companies and eliminating jobs in pursuit of a quick profit. Private equity, President Obama said, seemed too focused on financial engineering and the profit motive and paid too little attention to its impacts on broader society.

Even as President Obama toured the country to stump for his own re-election, his own campaign treasurer, Marty Nesbitt, was contemplating starting a private investment firm that focused on the positive aspects of growth-oriented investing. His brainstorming partner was a fellow Chicago executive, Kip Kirkpatrick. Together they dreamed of a different kind of private investment firm: One whose commitment to the welfare of communities, businesses and workers would play to the financial benefit of investors.

“We don’t like the term private equity because it immediately leads people to think of financial engineering and cost-cutting,” says Kip Kirkpatrick. “We like growth-oriented investing and building market leadership companies so we always referred to our company as a private investment firm or a next-generation investment firm.”

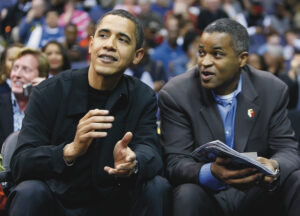

Six years before the US Business Roundtable issued its statement calling for companies to serve all stakeholders, Marty Nesbitt (above) and Kip Kirkpatrick (below) launched a private investment firm on the premise that a socially responsible approach could deliver outsized financial returns.

“If a company provides a value proposition not just to employees and customers and investors, but also a broader social value proposition, it should be worth more,” says Nesbitt. “It’ll be supported by policy over the long term. It’ll have community support over the long term. Revenues will therefore be stable. And it should be more valuable.”

There was limited data to support that theory when Nesbitt and Kirkpatrick launched their firm, the Vistria Group, in 2013. After all, that was six years before the US Business Roundtable issued its statement calling for companies to serve all stakeholders rather than just shareholders. In 2021, the Vistria Group stands as a compelling data point in the argument for inclusive capitalism. It raised $400 million to launch its first fund in 2013 and in the interim has raised three additional funds, the last of which closed this summer. That fourth fund, which closed at $2.68 billion, puts total assets under management at just over $6.5 billion.

Demand is strong from investors that include large pension funds, university endowments, companies and family offices. “Across the board, we’re excited and encouraged that we have many investors in our fund who take great pride in what we’re doing but also hold us to a high standard of performance,” says Kirkpatrick. “Everybody’s saying, ‘Of course I want high returns. But tell me more about how I’m getting those returns. Tell me more about who those underlying managers are. Are they diverse? Does it paint a picture of the America we want it to be or is it all the same firms who come from very privileged backgrounds?’”

The Vistria Group follows the same basic mechanics as traditional PE firms, raising money from accredited investors and then taking controlling stakes in businesses. But on its website, the firm describes itself as operating “at the intersection of purpose and profit.”

The two Chicagoans became friends on the basketball court, where their game was recreational but competitive, Kirkpatrick having starred as a three-year starter at Northwestern University. Among the players in their pick-up basketball circle was President Barack Obama, who in his memoir Promised Land portrays Nesbitt as one of his closest friends and advisors (see Sidebar on page 76).

Before starting the Vistria Group, their off-the-court accomplishments were substantial. As an officer of the Pritzker Realty Group, Nesbitt had co-founded and run as CEO The Parking Spot, the well-known owner and operator of off-airport parking facilities. Kirkpatrick had co-founded two healthcare-focused private equity firms and was serving as CEO of one of the nation’s leading independent mortgage lenders.

At the Vistria Group, the two men focused their investments in healthcare, financial services and education—industries that Kirkpatrick jokingly dubs, “healthy, wealthy and wise.” An example of their success at Vistria is Penn Foster, an educational company that enables adults to earn a high-school degree. Vistria invested in Penn Foster and also connected it with businesses looking to offer employees the chance to continue their education.

Kip Kirkpatrick starred as a three-year starter for the Northwestern men’s basketball team in the early 1990s. Years later, the sport would introduce Nesbitt and Kirkpatrick to one another as they played recreationally.

“There were four winners in this business model that we built,” says Nesbitt. “First, the students who received a better education and an opportunity for growth. The employers gained a better-educated and credentialed workforce, while customers received services or products from that better-trained employee base. But the broader community also benefited. The social cost of an uneducated population is real. So is the value proposition of creating optimism and opportunity for a community.”

To that list of winners a fifth entry can be added: The Vistria Group, which generated nearly 50% IRR on the business.

Frank Britt, CEO of Penn Foster, said that he had “always been impressed with the Vistria approach and I have lived it first-hand. They are earnest about their commitment to doing things the right way by working to infuse a values-driven approach with the nurturing and thoughtfulness of what it takes to build great companies. I can’t imagine investing and leading any other way now that I’ve experienced the power of being at the intersection of purpose and profit.”

Vistria enjoyed even greater returns on an investment in St. Croix Hospice, a business that helps make end-of-life care more accessible and affordable while supporting a crucial portion of the healthcare system—one that accounts for 10% of US healthcare spending, or roughly $400 billion annually. The Vistria Group still owns the overwhelming majority of the 24 portfolio companies listed on its site; all but two are in healthcare or education.

Such an approach is generating leads as well as returns. “We spend a lot of time thinking about where we want to invest and why, and then being pretty proactive about trying to find the right platforms in which to invest,” says Nesbitt. “Having said that, we’re seeing more and more owners and management teams who are thinking about bringing in a partner, calling us and saying, ‘We’ve heard good things about the way you approach adding value.’”

No word appears in larger type on Vistria Group’s website than “impact,” an aim the firm seems to pursue through more than its investments. In response to George Floyd’s murder and the protests over racial injustice that ensued, Vistria spoke with every company in its portfolio. These discussions resulted in each CEO of a Vistria-owned business writing to their respective mayor and local administration to call for greater action on inclusion and diversity. Vistria itself also phoned those mayors and donated money to accelerate the change for which they had called. These measures prompted a Wall Street Journal article headlined, “Vistria Group Turns to Portfolio Companies in the Fight for Racial Equality.”

Meanwhile internal conversations were led by Nesbitt and Phil Alphonse, who, like Nesbitt, is a Senior Partner and Black.

“I’d like to think one of the good parts of Vistria is we are trying to have an open, honest dialogue about how we feel about what happened to George Floyd, and about social injustice in general,” says Kirkpatrick. “It’s hard for me as a white male to fully appreciate how impactful this was. But one of the good things about Vistria is that it’s not just a group of white men. And we decided as a firm to raise the bar on new investments. The level of diversity on the board and as a company is now a key factor in whether or not we’ll do the investment.”

Vistria Group headquarters stand only a 20-minute drive from the University of Chicago, whose economics department is closely associated with the doctrine of shareholder capitalism from which Nesbitt and Kirkpatrick are offering a profitable, socially responsible adjustment.

Nesbitt thinks of it as a kind of “jujitsu” on capitalism—redirecting its tremendous power so that economic incentives align with social outcomes and beget a virtuous cycle.

“Consumers and voters are the same people,” says Nesbitt. “Consumers cast their vote more frequently than participants in democracy, whose opportunity to vote is less frequent. When consumers start saying, ‘Well, wait a minute—what product are you producing? Who’s providing my care or education? What are you doing to my community? And I’m not using your product or service if I don’t think it adds value, or if you don’t conduct yourself in a way that adds value.’ They’re then going to vote that way. And when they do that, politicians will join this trend. That’s the beauty of democracy and capitalism, is that participants get their say with their checkbooks and votes.”

“Our country has gone through a lot, between the pandemic, the political division, the awful social injustices,” says Kirkpatrick. “I think more and more, people are stepping back and saying, ‘If this is what capitalism leads to, boy I’m not interested.’ What we’re saying is that we believe that the future of capitalism is not only dependent on a new approach, but that approach makes good business sense.”

“Capitalism is not a science,” Nesbitt says. “We made it up. We made it up to make ourselves safer and more prosperous. If we invented it, we can change it.”

—