There are more slaves today than at any point in recorded human history. Many are hidden in the maze of vast, complex supply chains. Lulwa Rizkallah and Kathryn Casson spoke to four leading experts on what businesses can—and should—do.

There are 40 million people in modern slavery today, more than any point in recorded human history. Fifteen million are trapped in forced marriages. Forced labor comprises the remaining 25 million, of which the overwhelming majority—more than 60%—are associated with supply chains.

Modern supply chains are tiered. Tier one refers to the largest, most advanced suppliers that deal directly with multinational companies. Tier two suppliers are smaller and supply those in tier one, and so it goes down the chain. Accountability charts a similar course. Each company is typically responsible for ensuring the quality of the suppliers it deals with directly. A 2020 analysis by McKinsey hints at the scale and complexity of these chains—and the challenge facing businesses looking to impose uniform standards across them. Analyzing two Fortune 100 companies, they estimated each relied on roughly 4,000 suppliers in the first two tiers alone.

The International Labor Organization (ILO) estimates that modern slavery generates $150 billion in illegal profits every year—the only crime more lucrative is drug trafficking, which rakes in roughly $300 billion annually.

The pandemic has intensified the problem in two main ways. First, its economic fallout has left millions more vulnerable to exploitation and forced labor—the ILO estimates that 225 million full-time jobs were lost in 2020 and 1.6 billion informal economy workers were in danger of losing their livelihoods. Second, the pandemic has put workers’ rights—from the gig economy to warehouse workers—in the spotlight. Stakeholders are paying more attention to what companies are doing, and they are demanding more meaningful action.

Brunswick spoke with leaders from four organizations on the front lines of the fight against modern slavery. Whether building coalitions and partnerships with the private sector, providing research to investors, or benchmarking companies, they represent some of the most informed—and influential—voices on the issue.

What enables modern slavery, and what steps can businesses be taking to address it?

ANTONIO ZAPPULLA: Modern slavery is the symptom of a larger set of deep-rooted issues—poverty, a lack of education and socio-economic inclusion, and gender and racial discrimination. The global economy is also still very much geared to favor short-termism over stakeholder value, which only serves to fuel the problem.

In terms of what needs to be done, modern slavery can only be addressed through a global response, one which combines the forces of multiple players—front-line NGOs and activists, the legal, investment and business sectors, policymakers, academics, economists and journalists. Facilitating partnerships is at the heart of the Thomson Reuters Foundation’s inclusive economies work, which encompasses all our anti-slavery initiatives and our efforts to foster sustainable and responsible business models. I cannot overstress the critical need to strengthen the wider ecosystem.

Antonio Zappulla, Thomson Reuters Foundation CEO.

MATT FRIEDMAN: A lot of it is a general lack of awareness. We all have a sense of what forced slavery and modern slavery is, but we can’t picture what it actually looks like. If you don’t know it’s there, if you don’t understand it, you’re not going to be able to create the tools and approaches to protect your business.

The second is a lack of priority—seeing this as something to be checked off a list rather than recognizing it’s emerging into a powerful phenomenon that more companies are being caught in.

Lastly, most manufacturers are not looking below tier one. Manufacturers have been auditing tier one for a long time; nobody ever really asked them to go below that level. But the expectation now is that they have to. For that to happen, there will likely be a lot more sharing of audit information between and among brands. We will see major shifts in the way manufacturing is done simply to accommodate the requirements that exist related to this legislation.

FELICITAS WEBER: KnowTheChain benchmarks demonstrate that companies focus heavily on supplier audits, yet these can fail to detect forced labor. For example, in 2018 an independent investigation identified forced labor at the Malaysian rubber glove manufacturer Top Glove—a finding that 28 audits in the two years prior to the investigation had overlooked.

Matt Friedman, CEO of nonprofit Mekong Club.

MATT FRIEDMAN: Responsible recruitment is an essential part of this whole process—ensuring that employees that come from one country and end up in another destination have no debt is an extremely important part of the process.

FELICITAS WEBER: We found that some workers in apparel supply chains have to pay as much as $4,000 just in order to get a job—more than a year’s salary. This kind of debt bondage affects roughly half of all forced labor victims.

Another important step businesses can take is to address the fundamental power imbalances between themselves and their workers. KnowTheChain’s analysis has found that forced labor thrives in situations of inequality and discrimination. This harms the most vulnerable workers, especially migrants and women.

Few companies seem willing to address these power imbalances. They could do so by focusing on grassroots and worker-led approaches—ensuring that workers identify the full extent of any rights violations, for example, and that workers design, implement and verify solutions. Academic research shows that such a worker-centric approach is more effective and drives better outcomes. Across sourcing countries, for example, apparel factories in which unions and collective bargaining are present have higher compliance levels.

In addition, companies can fix irresponsible purchasing practices: last-minute changes to orders, downward pressure on pricing and delayed payments, to name a few. These create demand for forced labor. An ILO survey of more than 1,500 suppliers across 17 sectors found that 39% of suppliers reported having accepted orders that did not even cover the cost of production—let alone the costs of decent work and living wages.

Equally, as the length of time between the delivery of an order and payment by a buyer increases, weekly pay for workers decreases significantly. Responsible purchasing practices—prompt payment, accurate forecasting and reasonable lead times—help prevent forced labor and ensure decent work and living wages.

Felicitas Weber, former Project Director at KnowTheChain.

Is there reason for optimism, given that the pandemic has intensified the focus on ESG?

ANTONIO: Modern slavery sits within the S of ESG, which is often seen as the most complicated letter to adopt and monitor. A wide range of issues fall under this category, and there’s a lack of shared benchmarks and available data at the moment.

Yet we recently released a white paper called ‘‘Amplifying the ‘S’ in ESG,” which narrowed the focus to four key benchmarking themes, one of which was high-risk labor. To produce the paper, we spoke with more than 100 stakeholders. And we kept hearing the same misperceptions: Social performance is less financially material than environmental performance; social risks are hard to measure; and by following local laws, companies are compliant even if labor practices are poor.

This last assumption is one which creates the conditions where modern slavery can flourish. It’s critical that both businesses and investors don’t equate eradicating forced labor in supply chains with diminished returns. In fact, our paper demonstrates that companies with better scores on the social dimensions of ESG trade at a premium in comparison with their peers. Businesses within the purpose-driven B Corp movement, for example, have experienced an average year-on-year growth rate of 14%—28 times higher than the national average in the UK.

SERENA: Walk Free works closely with investors through the Investors Against Slavery and Trafficking initiative. And they’re seeing modern slavery as something that goes beyond ethics. As they highlighted in a statement, business models and value chains that rely on underpaid workers, weak regulation or illegal activities such as forced labor and other forms of modern slavery drive unsustainable earnings. Greater transparency is not only expected by consumers and investors—it’s increasingly required by law. We’ve seen laws on supply chain transparency, human rights due diligence and customs regulation for goods made with forced labor across several countries in just the last few months. This exposes companies to significant legal and reputational risk.

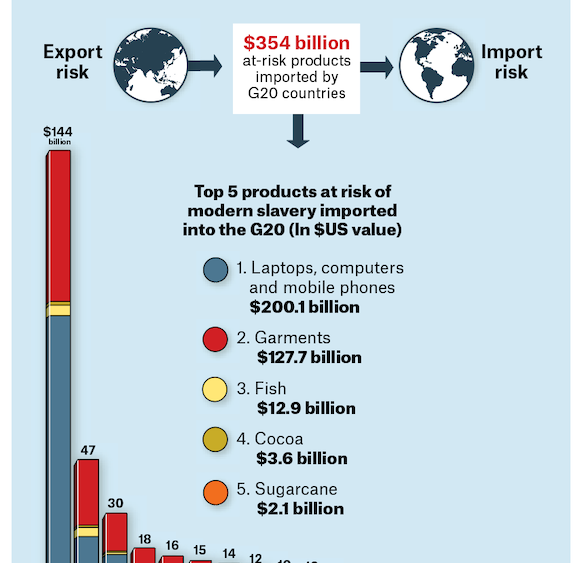

In one sense, modern slavery is geographically concentrated. Two-thirds of modern slaves are in Asia, and over half are thought to be in five countries: India, China, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Uzbekistan. Yet because supply chains are global, modern slavery shows up in almost every country and every product. Each year, G20 countries import more than $350 billion worth of products at risk of being made by slave labor—nearly 40% of which goes to the United States.

Serena Grant, Head of Business Engagement for international human rights group Walk Free.

So what does real leadership on modern slavery look like?

ANTONIO: Real leadership on modern slavery takes courage. And this is something we recognize through our Stop Slavery Award, which doesn’t credit companies with being “slave free,” but instead rewards those that have stuck their heads above the parapet, are open and transparent about their operations, and have set a gold standard in efforts to eradicate forced labor from their often vast and complex supply chains. Over the last year, we’ve been so heartened by the number of companies who have willingly joined us for a series of roundtables to discuss issues related to human rights and supply chains, and to share best practice.

Australian ethical brand Outland Denim has demonstrated remarkable leadership through prioritizing the dignity of its workers and centering its business model around positive social and environmental impact, as well as economic returns. In addition, Adidas’ efforts to safeguard the rights of migrant workers and address modern slavery risks in the lower tiers of its supply chains exemplifies how a global company can lead by example.

SERENA: Real leadership involves driving meaningful collaboration. No single organization can tackle all of the systems that allow modern slavery to flourish. To be effective, corporate leaders must work with industry peers, governments and civil society to identify what those systemic failures are and take action to address them. It also involves being transparent, not just about risks, but also when they have found modern slavery cases. We always applaud companies that find instances of exploitation in their supply chain and then act swiftly to protect victims and provide remediation. The more companies that are open about this, the more others will start fixing the problem rather than shying away from it. In fact, we should get to the point where it is unusual to not be identifying instances of modern slavery or related exploitation, given we know how prevalent it is in certain industries.

FELICITAS: KnowTheChain’s 2021 apparel and footwear benchmark identified forced labor allegations at more than half of the 37 largest global apparel companies, with some companies facing as many as four allegations. Typically, companies make real efforts to address forced labor only after they have been called out for specific allegations. Leadership begins by companies taking proactive steps to address forced labor risks across sourcing countries and supply chain tiers, rather than waiting for allegations to come to light.

And while on paper most corporate policies prohibit forced labor, in practice, reports of forced labor cases continue to emerge. As they work to prevent abuse, companies must show leadership when it comes to remediating rights abuses. In the best-case scenarios right now, companies report that they ensure that suppliers provide remediation to workers. This is positive, but it doesn’t consider the role the company itself plays through its purchasing practices. Pricing orders inadequately, for example, means that pricing does not cover the full costs of compliance with a company’s code.

We hope to see more follow the example of US sportswear company Brooks, which reportedly shared the cost of providing remediation to workers with its subcontractor.

MATT: Leadership really has to come from an emotional attachment. You can’t mandate or delegate this—a leader has to own it. And they act because it really bothers them that this injustice exists. They make public statements. They give interviews. In some cases, they come right out and say they have identified violations. They are communicating it’s relevant and important enough that they have to do something to address this.

The Mekong Club helps organizations put in place sustainable systems and procedures that protect them and their workers and their brand, and allow leaders to talk about this as being something they care about.

There are unsung heroes out there within the private sector. If you look at the factories in Asia and compare where they were 30 years ago and where they are today, it’s because of the private sector’s insistence on regularly going in and auditing and re-auditing and correcting.

The real heroes out there are those in the private sector who have been doing this. They are often perceived as the villains, yet some of the biggest achievements that we’ve seen have come as a result of brands doing what they need to do.

Some leaders have been taking this on for many, many years. They might not get a lot of credit, but as a result of what they’ve done, the world is a better place.

–

Authors Lulwa Rizkallah and Kathryn Casson are both former Brunswick Directors.

Graphic: Peter Hoey

More from this issue

The S in ESG

Most read from this issue

Power in Numbers