Brunswick’s Jon Miller, founder of the Open For Business coalition, talks about global LGBT+ rights with Phyll Opoku-Gyimah—a.k.a. “Lady Phyll”—UK Black Pride founder and Kaleidoscope Trust Executive Director.

As part of a celebration of gay prideMonth in June 2021, Brunswick organized an online event featuring Phyll Opoku-Gyimah, widely known as Lady Phyll, human rights activist and founder of UK Black Pride and Executive Director of Kaleidoscope Trust, a UK-based charity working to uphold the human rights of the LGBT+ people across the Commonwealth. Brunswick’s Jon Miller, a founder of the Open For Business coalition, served as host.

As a Black woman, lesbian and mother, Lady Phyll brings an awareness of the multiple challenges LGBT+ people face. She is on the global Pride Power List andGQcalls her “a crucial voice in British intersectional equality.” She talks about her experiences, the fight for equality and the role business can play.

People sometimes ask, “do we still need Pride?” or “aren’t we overdoing it now?” Why do you think Pride matters now?

We are not living in some ideal world, where we all have the rights that we deserve. So Pride is much more than just a celebration. It really is about looking back to the roots of how it started—the Stonewall Riots, police brutality, lack of safe housing and shelter for our trans and gender-nonconforming and nonbinary siblings. It is about the systemic violence that was there, that was on our bodies.

Prides very much tell that story, especially as a Black or POC-Queer person. We want to have pride of place, to take pride in who we are, and that means that it’s still very important to have a space that we can be unapologetically ourselves.

In addition to the UK, there are Black Prides in cities in the US and Europe. Why do we need a Pride for Black or POC-Queer people?

You know, Jon, I’ve got to the stage where I’ve stopped answering the question about, “Do we really need a Black Pride?” The question I want to be asked is, “What would happen if there wasn’t a Black Pride?”

The mainstream LGBT+ activities are not always as inclusive of our differences as we would like them to be. When we think of the word “intersectionality”—which is not a synonym for diversity—it really is about having a clear lens to how and where we see ourselves, especially because of all of these many facets, the oppressions that one has felt from the racism, the sexism, the misogyny, the issues of Islamophobia, faith, religion, belief, class: There’s so much, so many types of experiences. Prides and other movements allow us to see ourselves—you can’t be what you can’t see.

UK Black Pride was really born out of a frustration, a need and a desire to really come together and have that celebration, but also to look at our shared commonalities: how we connect and collaborate with one another. And how we also feel extremely empowered when we turn up the volume on society, making it absolutely impossible for the volume to be turned down on us.

That is what Pride is about—togetherness and solidarity, love, hope and aspirations.

Prides allow us to see ourselves—you can’t be what you can’t see.

This time last year [June 2020], we were really at the peak of Black Lives Matter protests in response to the killing of George Floyd. We saw lots of CEOs speaking out, companies making statements, lots of black squares on Instagram, et cetera. Some were saying all that was just performative. What advice could you give to organizations when they want to use their voice, but they’re not quite sure how?

It’s really important for us to take that word, “allyship”—I very much think that allyship is situational. Where we had seen this massive resurgence of Black Lives Matter, rightfully so, following the murder of George Floyd, I saw a lot of performative action—black squares, as you say. And then some people would get tired of it and say, “Oh, I’m just gonna put up a picture of my banana bread.”

A key thing that businesses can do is ask the question or speak to your employees, those who are Black and brown, Queer, who are working for you. If you have strong values, you should be able to speak to them and say, “How are you doing today? How do you feel?” I know I was exhausted, physically and mentally, by what I was seeing on social media—people sending particular memes or wanting to have the conversation or calling me to speak about, “What can we do differently?”

We have to understand the demographic of our organizations, the demographic of those who we are supporting and assisting, not just here but abroad. Things that are performative—they stay there for a couple of weeks and then move away—that’s not being true, that’s not being authentic, that’s not being real.

We need to understand that lives are impacted in such a significant way when it comes to issues around racism, structurally and systemically. And we’ve got to do our best to do better, to be better, and to “usualize” the conversation, not just in a moment, but continually.

You used the word “intersectionality.” What does that mean for you?

It means that we can’t have rights and equality for LGBT+ people without anti-racism, without an end to transphobia, homophobia, biphobia. It means we can’t not think about how the economic inequality experienced by LGBTQ People of Color and Black people intersects with the movement for racial equality. I always use the word “intersectionality” because I really cannot speak about racism if I’m leaving at the door my sexual orientation and identifying as a lesbian; or speak about sexual orientation without speaking about class and how that plays out. So those intersective vectors are really important when looking at LGBT+ rights globally.

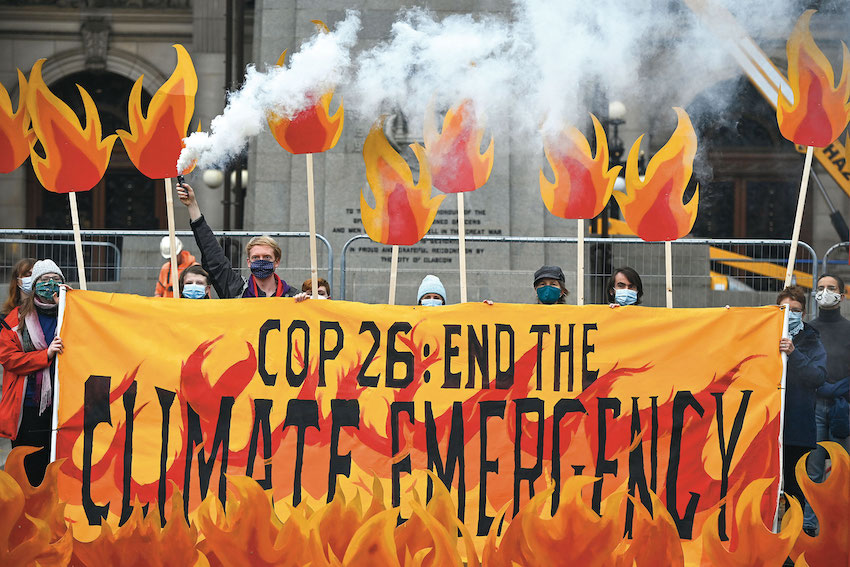

Lady Phyll addresses a Pride event, July 21, 2021, in Parliament Square, London, where demonstrators sought a return to Pride’s original spirit of protest and community.

How would you describe the situation facing LGBT+ people around the world? It’s a complicated picture out there. Are you hopeful? Do you see progress?

We’re seeing a bit of both, progress and regression. Kaleidoscope Trust—for those who don’t know, we’re a small charity, an international human rights charity, that works to uphold human rights for LGBT+ people. We work primarily within the Commonwealth and also work with Open For Business. Our work is very necessary, very important, because it’s about helping to ensure a free, safe and equal world for LGBT+ people everywhere.

We can talk about the success or progress that’s been made—Trinidad and Tobago, Botswana, Gabon, Repeal 377 in India. But we’re also seeing 44 Ugandans arrested, or the 22 LGBT+ people in Ghana being detained unlawfully, injustices in Nigeria, in Hungary. So we’ve got rights in certain places, equal marriage. But that’s not the be-all and end-all.

So yes, regress and progress; unequal and uneven. That’s how I see it. We’ve really got to re-imagine a world where we all have rights. We have to be, I would say, almost radical, in our approach for human rights for all.

What is the most powerful thing, do you think, that businesses can do to move forward LGBT+ rights in places where it’s a challenge?

I think corporations, especially the big ones, often go beyond their role as companies. They lead on setting working standards, and often cultural standards. They operate as opinion leaders. As such, companies should be more actively involved in becoming part of the solution, rather than part of the problem. That carries more responsibility.

Workplace discrimination is not always obvious, but most of the time goes below the usual radars, and this is why it becomes crucial for corporations to have in place, first of all, really strong policies. But also, culturally, they should have routines that allow people to enjoy equal rights and treatment, regardless of their gender, their sexual orientation. Research, as you see in Open For Business, shows the ways that companies can respond to diversity to help their employees feel psychologically safe—to avoid incidents of racial discrimination or mistrust of authority or other organizational issues.

I really need to labor the point about Open For Business: You are doing absolutely the most vital work, which is groundbreaking. I think it’s time for companies to open up and have these real discussions about racial inequality, about systemic racism, inside and outside of the workplace, to have these conversations so that we’re usualizing them—diversity talks, workshops, or things around themed months—so that they don’t feel decorative.

I really cannot speak about racism if I’m leaving at the door my sexual orientation and identifying as a lesbian.

How can those not in the LGBT+ community help their LGBT+ colleagues in the workplace?

First, you can do your homework, so that we’re not relying on our LGBT+ siblings, comrades, colleagues to talk about their lived experience. Because that may open up trauma and they may not be ready. I always say, “Google is your friend.” There are so many books, and websites like Kaleidoscope Trust, or UK Black Pride. I’m shamelessly plugging here, aren’t I, Jon?

Second, I would say there’s something about the word “solidarity.” If your allyship is not rooted in solidarity, then it’s not “allyship.” You can’t say that you’re for one bit of equality, but not for another. It has to be right across the board; we have to look at even solidarity with an intersectional lens as well.

Third, I would say put your money where your mouth is. We can donate, we can sign petitions for groups and causes that support the work of upholding human rights, strengthening movement-building and capacity-building.

All of that is important: homework, making sure solidarity is at the forefront of what you do, putting your money where your mouth is. And then just usualizing the conversations, making sure that it’s not a seasonal thing, but 365 days a year, and ensuring that your policies value and respect the difference within your organization.

Regarding working for LGBT+ rights in other countries, a question that we often hear is, “Isn’t that a sort of form of neo-colonialism?” How can we make sure that the work that we’re doing isn’t accidentally some new form of imperialism?

A big question and absolutely an important one. It’s important to remember that homophobic laws across several Commonwealth countries are imported laws. People that were under this occupation by European countries were never asked how they felt about those laws.

Before European colonization, we see a far different, and I think a more relaxed, attitude toward sexual orientation and gender identity, especially throughout Africa as a continent. If we take a closer look at Africa, for example, we’ll see that homosexuality goes back in history—it’s not un-African to be gay. Many African countries had never even seen gender as binary. Nor did they link autonomy to gender identity. If you look at local cultures in countries like Uganda, Botswana, or even Nigeria, they have always been aware of different sexualities.

At Kaleidoscope Trust we really make sure that we carefully navigate these different political systems and social dynamics. This is why we never ever dictate to our partners about how they should work or what they should work on, and what they should focus on. For us it’s about how do we listen? How do we hear? How do we make that space? How do we also provide the resources for them to act independently and really formulate their own agendas, coalitions, campaigns, in the way they think most appropriate to them?

We are not here to berate, point the finger, or to say, “This is how it would work.” It really has to be a collaboration.

There are some pretty toxic voices out there at the moment—some who paint the whole equal rights conversation as “culture wars,” for instance. How do we inject a bit of compassion and kindness and nuance into the conversation?

First and foremost, there really shouldn’t be a debate about trans rights. Trans rights are human rights, and the onslaught that our trans siblings are facing, especially here in the UK, but around the world, is unacceptable on every level. We cannot leave our trans siblings behind.

I think we encourage compassion and intelligence by demonstrating compassion and intelligence. The propaganda and vitriol against our trans non-binary siblings is awful, it’s horrendous. It actually makes me sick to my stomach. Trans people don’t just want to survive; they want to thrive. We can’t let them go it alone. We have to get angry and we have to stand up for their rights and say, “This is not OK, and it will not be done in my name.” We’ve seen such a backlash against the amazing work being done, here and abroad. We have got to stand up, show up, show out, speak up and speak out against this.

Companies can do a lot to lead the way. They can show us how you stand up for creating meaningful, strong policies that are actively inclusive of trans people in a work environment. All trans people. It’s about making sure you’re putting something in place for those that require those gender-affirming conversations. Those who refuse to be boxed in by gender.

We cannot afford to just stand still. There’s a quote by Bishop Desmond Tutu that I’ve used for years. He says, “If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.” We really have to think about which side of history we want to be on.

You famously turned down an appointment to MBE. Obviously a personal decision, but one that carries a political resonance. Can you talk us through that?

MBE stands for “Member of the Order of the British Empire.” Now, anyone on this call will understand how the words “empire” and “colonization” are toxic. The work that we do within Kaleidoscope Trust, Open For Business and many other brilliant organizations, is about reversing these colonial-era laws.

As somebody who has founded UK Black Pride, who works in international human rights, who is a trade unionist, I couldn’t accept something that elevates itself over the people I serve. And I couldn’t accept anything whilst I still know there are so many countries, especially a country that I’m from, Ghana, that still criminalizes LGBT+ people.

So I declined, gracefully. That was probably my seventh letter back to the Queen. And I take nothing away from those who have chosen to accept this accolade. But, for me, there’s so much work to be done. I could make a joke of it and say, “How does one queen bow down to another queen?”

Who inspires you to keep going with this work?

I’m inspired by the activists we work with. I’m inspired by Black women, Black Queer women, faced with being excluded and not feeling seen. I’m inspired, really, by many people that touch my life, including yourself and Open For Business. So many people, it’s hard to pin it down. My life is not just this straight, narrow road. It has so many different turns, and I get and seek inspiration from different people.

I keep going because my daughter, who is a 26-year-old young woman, is proud that her mum talks openly about being a Black lesbian and the work she does. We’ve overcome hate crime and death threats and held each other at times where I’ve just wanted to retire. But we’re there for each other.

Photographs: (from top) Kofi Paintsil; Mark Kerrison/In Pictures via Getty Images

More from this issue

The S in ESG

Most read from this issue

The Paris Peace Forum