A Brunswick survey finds a disconnect between what business leaders think employees want, and what workers actually value in their leaders.

Optimism has become a leadership article of faith, a trait executives cultivate and project to steady organizations. Yet a Brunswick survey of Swedish business leaders and employees suggests this emphasis may be misplaced. Workers rank optimism low among the qualities they want from leaders. What they value instead points to a different model of how confidence actually takes root.

The survey, covering executives across 30 large enterprises and more than 1,000 employees, also reveals sizable gaps between what leaders believe and what employees experience. Leaders consistently overestimate both workforce optimism and their own effectiveness at displaying the traits workers find most valuable.

The findings echo broader international research showing that executives often misread employee sentiment and lose touch with what their teams want. But the data also points to specific, actionable steps leaders can take to narrow these gaps and build the confidence they assume already exists.

The Optimism gap

Our survey found that 87% of leaders felt somewhat or very optimistic about the future of their company. And nearly three out of four leaders (73%) believed their employees shared that view—yet only 62% of employees actually did. The 11-point gap widens dramatically when the question shifts to global outlook. Thirty-three percent of leaders reported optimism about the world’s future; only 17% of employees shared that optimism.

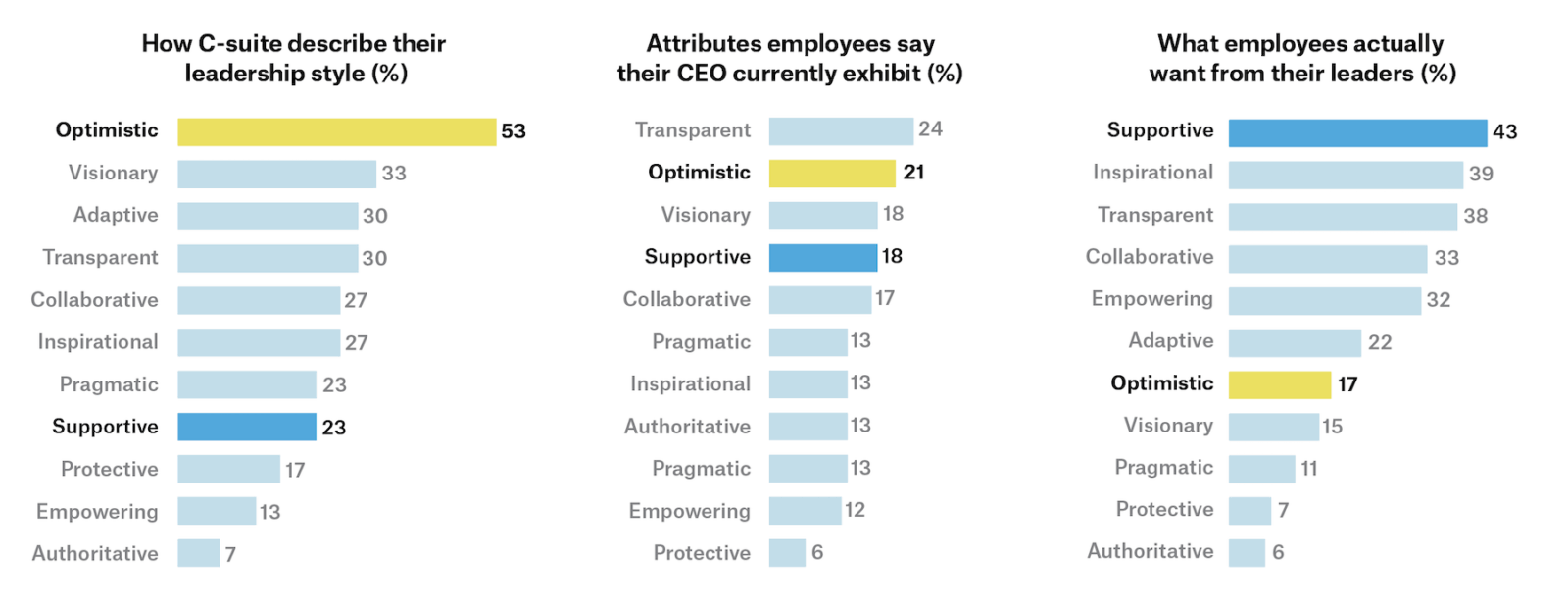

Employees are not looking to leaders to undo their pessimism. When we asked employees to identify the most effective leadership styles, optimism fell closer to the bottom of the list than the top. More than half of executives (53%) described their own leadership style as optimistic, yet only 21% of employees saw that quality in practice, and just 17% considered it the most important trait.

Nearly half (43%) of employees instead said that a supportive leadership style was most valuable—and only 18% believed their leaders demonstrated it. Inspiration, the second-most valued leadership style at 39%, saw a similar gap: 27% of executives described themselves as inspirational, but only 13% of employees recognized that quality in their leaders.

where alignment exists

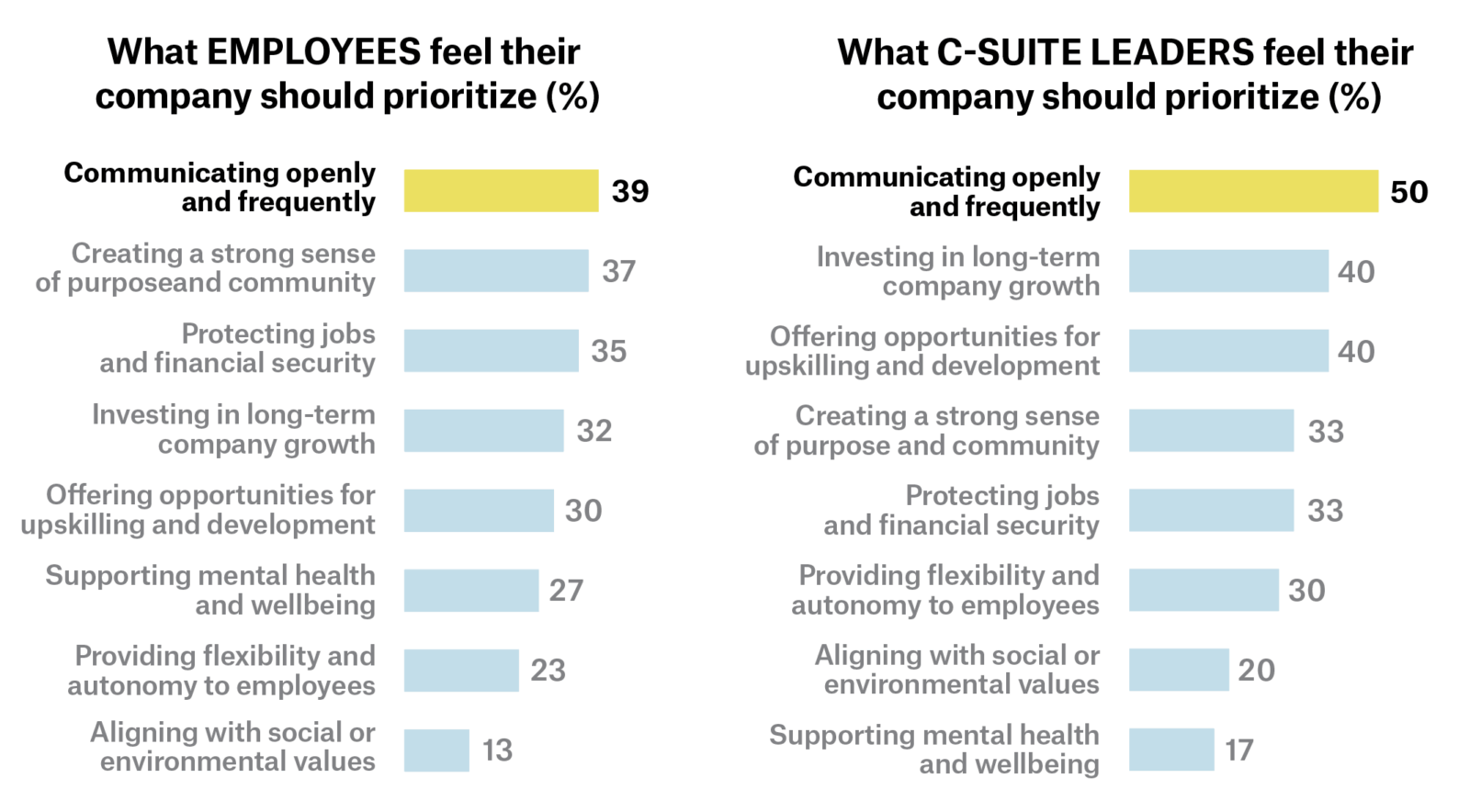

Transparency is an important area where expectations converge. Both leaders and employees rate open and frequent communication as essential. This alignment may reflect that transparency has already become an established expectation in many organizations, making it easier to strengthen. Employees want clearer insight into how leaders make decisions, how the company plans to navigate external pressures, and how individual roles contribute to broader objectives. When leaders provide that clarity, employees gain stability even when wider uncertainties remain.

The survey results also highlight resilience. Employees who describe themselves as highly resilient show greater optimism about both their futures and their companies. They express stronger confidence in their personal stability and report higher levels of psychological safety at work. These findings point to a straightforward conclusion: optimism is not manufactured through rhetoric. Instead, it emerges when people feel supported, informed and secure enough to manage uncertainty. Leaders who invest in those conditions build teams better equipped to absorb disruption and stay engaged.

practical implications

The survey suggests several actionable steps. First, leaders can narrow the optimism gap by acknowledging challenges more directly. Employees do not expect leaders to deny risks. They want an honest assessment of what the organization faces and a clear view of how decisions are being made.

Second, support must be tangible. Leaders naturally focus on what drives results. But employees across the organization need recognition and a clear sense that leadership values their work—particularly when high-priority initiatives threaten to overshadow other contributions.

Third, leaders should deepen conversations about external pressures rather than avoid them. Rather than trying to protect employees from uncertainty, leaders should include them in those conversations and let them share their confidence. Many employees already recognize wider instability. They want to understand how their company intends to remain resilient. When leaders share that reasoning and invite questions, trust begins to strengthen.

Each of these steps requires the same investment: time spent communicating clearly, consistently and honestly. Companies that make this commitment gain employees who absorb disruption better, adapt to change faster, and maintain performance through uncertainty because they trust their leaders and understand how their work contributes to resilience. In these organizations, optimism stops being some-thing leaders project and becomes something employees experience.

For the full survey, click here.