Netflix’s hit drama Squid Game is a dystopian South Korean adventure that has riveted global audiences, breaking records for Asian-themed programming internationally. It is just one of a recent slate of original Netflix content from Asia taking the world by storm, a list that also includes the Japanese manga-based series Alice in Borderland and the Indian coming-of-age romance Mismatched. Together with Western programs featuring Asian casts, such as teen comedies To All the Boys and Never Have I Ever, and the American reality show Bling Empire that follows the wildly wealthy in Los Angeles’ Asian community, this programming meets a growing appetite for Asian representation.

Counterintuitively, such successes are created with a focus less on the region or the Asian community globally and more on each individual culture within what is arguably the world’s largest and most intensely diverse market. Reports have projected that Netflix’s investment in local content in Asia-Pacific will reach $1.9 billion in 2023, equivalent to 47% of its revenue. The expenditure will be driven by South Korea, Japan, India, Australia and parts of Southeast Asia.

Dean Garfield, Netflix’s Vice President of Public Policy, has been working to build the platform’s reach through its global public policy expertise from his base in Singapore, right at the heart of Asia. His focus is on meeting Netflix’s strategic objectives by cultivating local film industries and amplifying their impact.

Often in the entertainment industry, global public policy is decided from an office in California, a cultural distance that is not lost on viewers outside the US. Having spent the first two and a half years of his Netflix career in Europe, based in the Netherlands, Garfield saw a move to Singapore as a tremendous opportunity, spurred by the platform’s growth in Asia and the vibrance of the region. Not only could he learn directly from the region, he would also bring value from his experience in Europe, with its plethora of languages and cultures, to Asia.

Netflix’s focus on telling the best local stories possible resonates in Asia, and the stories that develop out of that market are finding resonance well beyond their local origins. Despite successes like Squid Game, Netflix is still in the early stages of operation in Asian markets, and has had to navigate difficulties including lack of distribution infrastructure, regulatory barriers and developing a nuanced understanding of a very diverse region.

“One of the major differences between storytelling traditions in some Asian countries and those in other parts of the world is that the physical infrastructure is often not there,” Garfield says. “Netflix is working to build that in places where it hasn’t existed before—partnering with local industries to create ecosystems that can sustain themselves in the long term.”

We’re trying to find the best stories that resonate most impactfully locally, and then working hard to create something that’s excellent, that hits at home.

A critical part of that infrastructure build involves a proprietary back-end distribution network called Open Connect. Hardware is distributed to local ISPs that allows them to store Netflix streaming content, reducing stress on their own servers and pipelines. The result: Where other streaming platforms routinely crash during waves of popular activity, Netflix is able to deliver consistently, even during the surprise popularity of Squid Game, when over 100 million viewers around the world were streaming episodes in the opening weeks. Open Connect is provided at no cost to network operators, and Netflix also provides them with technical expertise and ongoing monitoring and issue resolution to ensure that content can be delivered to viewers in a seamless manner.

Technological hurdles vary widely across Southeast Asia. Many governments have already invested heavily in technological frameworks and solutions to bridge the digital divide. Singapore is at the forefront of such efforts, building fiber infrastructure connections to nearly all individual homes in the city-state.

“Interestingly, we’re just beginning our journey in Vietnam and one of the things that we found there is that the deployment of smart TVs is as compelling as in many western European countries, because of the supply chain that exists there,” Garfield says. “So the biggest barrier there isn’t necessarily digital.” There are some issues around digital payments that Netflix is working to address by exploring partnerships with local payment providers, he says. “But, overall, technology has not been the biggest challenge.”

A larger issue involves finding the right partners, given the competitiveness for talent recruitment in the region, he says. That problem is compounded by the amount of work that is required to develop original content.

“Storytelling captured on film or digitally is highly labor intensive,” he says. “And that’s why the economic impact is so large when we produce any show. If you’ve ever watched the credits at the end of any Netflix show, it goes on and on—that’s really how many people worked on it.”

In addition to building streaming networks, governments are developing policies that incentivize content creation, allowing networks to generate the magnetism and energy that will keep local creators active at home, rather than relocating projects to more welcoming countries.

Dean’s Must Watch

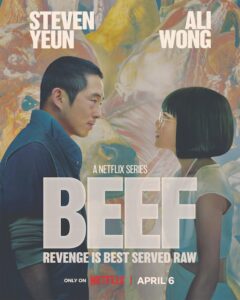

Netflix’s show Beef, which premiered in April, is one that Dean Garfield recommends as an example of how “highly localized stories that have a human connection” can translate to a wider audience. “That builds from our experience operating in other parts of the world including Asia,” he says. Beef is a comedy-drama starring Steven Yeun (known for The Walking Dead and Nope) and stand-up comedian Ali Wong (Baby Cobra). They play two seemingly normal personalities wrestling with their own disillusionment who collide in a road rage incident that sparks a war of revenge that takes over their lives. The show features an all-Asian cast and the crew that worked on it was also largely Asian.

“In a lot of places, we’re a first mover, bringing all that together,” Garfield says. “We’re partnering locally to create an ecosystem that can sustain over the long term—and we are really a company that’s very focused on building for the long term.”

Netflix rolled out its Grow Creative initiative, first in Australia and now the UK, to build a pipeline of creative talent. It has opened a hub of 10 soundstages in Tres Cantos, north of Madrid, Spain, a site that has grown into a small city around those stages.

At the heart of Netflix’s strategy is its approach to localization. “We’re not trying to bring a Netflix lens to the world,” Garfield says. “We’re trying to find the best stories that resonate most impactfully locally, and then working hard to create something that’s excellent, that hits at home. If it hits at home, it perhaps hits elsewhere. That local resonance leads them to be popular in more places.”

Access to a global cultural zeitgeist begins from being connected to the countries Netflix operates in. Shows like Squid Game, Alice in Borderland, the Indonesian comedy-drama Ali & Ratu Ratu Queens and the Thai film Hunger tell human stories in a local context. Done right, such stories are compelling to people outside that cultural context.

Garfield is deeply passionate about bringing these local stories to life, and he says Netflix has many tools to help elevate such content to the world stage. With more and more Netflix subscribers watching foreign content—60% of Korean content is watched outside of South Korea—the platform has been at the forefront of pioneering advanced subtitling to further enable consumer experiences. From crude roots in the earliest days of talking films, voice dubbing, where foreign language actors recreate the original dialog, has also reached a level of artistry.

“When I was growing up, dubbing was a joke—you would watch it to laugh, not to actually enjoy the show,” he says. “There’s so much innovation that’s happening in that space that it’s no longer a barrier to enjoyment.”

Ultimately, Netflix does not see itself as a disrupter, but an enabler. “Our shows are a reflection of culture, and culture is a reflection of identity,” he says. “It’s how people see themselves; how they want to be seen. We recognize that, and we recognize that in order to do it well, we have to be respectful of those identities.”

—

Additional reporting by Yan Tong Goh, an Account Director in Singapore. Before joining Brunswick, she served in Singapore’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.