Simon Mundy has written a book, and a cartography, to help navigate the world of ESG. He delves into the key ESG issues encompassed in "Race for Tomorrow: Survival, Innovation and Profit on the front lines of the Climate Crisis."

Race for Tomorrow is the result of a two-year project that took Mundy across six continents and 26 countries investigating what he describes as “the single biggest story of the century: humanity’s race to respond to climate change”.

Mundy took an “old-fashioned reporting approach” to the project. He got on the road to “wear out my shoes” talking to the people directly impacted by climate change, all from very diverse backgrounds.

“It was an incredible learning experience for me. It’s awakened me to the incredible urgency of the problems that we face but also the power of the solutions that are being developed,” he says.

Now in his role as Moral Money, he keeps digging into the business and financial angles of the issue. Every chapter of the book tackles a country or group of countries which can be matched with the main ESG themes the industry is facing.

In that sense, Mundy’s book provides valuable insights for ESG professionals, corporate sustainability practitioners, and investors interested in integrating ESG factors into their strategies. The stories that Mundy has documented, portraying the human face of the climate crisis, are the sort of qualitative data that these professionals are not going to find elsewhere.

Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity. To listen to the full interview, click here.

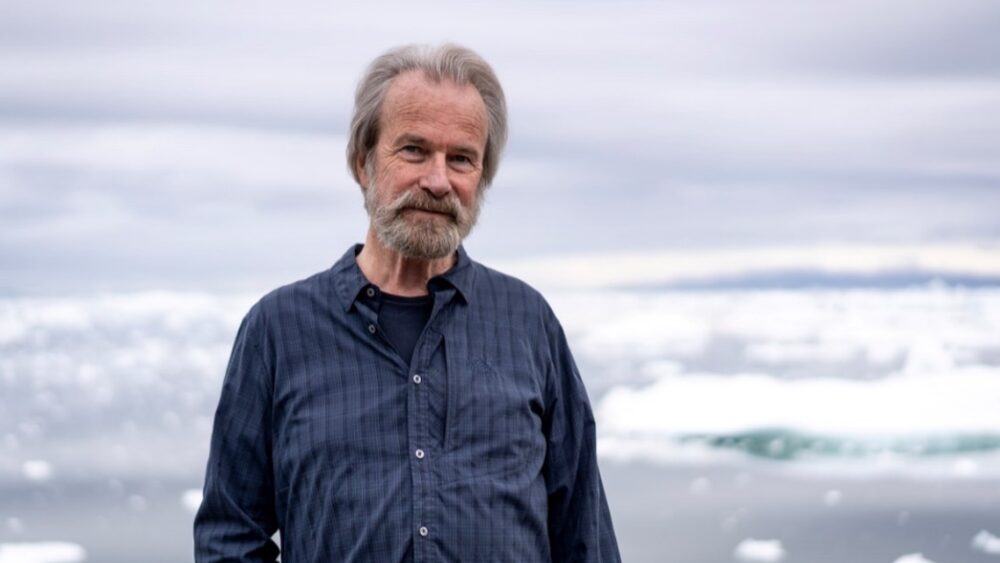

Konrad Steffen’s work on the Greenland ice sheet made him one of the world’s most respected climate scientists.

Greenland and the Arctic melting ice is what captures people’s imagination about the consequences of climate change. There you interviewed indigenous hunters, Greenland’s mining minister and the late climate scientist Koni Steffen.

Koni Steffen was one of the great climate scientists of his generation. He worked on the Greenland ice sheet for the best part of three decades. Every year he would go there for weeks or months at a time. He had his camp built on the ice. He realised that the ice of Greenland was shrinking and disappearing far more rapidly than anybody had previously realised. He realised the ice was moving towards the sea and thus melting far more quickly. It is sort of a self-perpetuating cycle.

It was becoming much more dangerous. The ice was breaking apart cracking these enormous crevasses in the ice that didn’t exist before. I met him the day before he was flying on a helicopter back to his camp. It was going to be his ultimate visit, taking the camp apart because he was approaching retirement age. The next day he flew to the ice sheets. Three days after that, he was working on the ice, and he fell into one of those crevasses. He was never found.

His life came to an end in an incredibly tragic way but what he achieved during that life was phenomenal. He’s not with us anymore, but his work still is, and the question is, what use are we going to make of that?

The melting of the sea is having some significant implications for the people who live in Greenland. But there’s a flip side to it: mining. When I met the mining Minister of Greenland, he was saying, “Yeah, culturally, this disappearing sea ice is a disaster for our people. But economically, is going to be a boom.”

I spoke to one London listed mining company, a small cap called Bluejay Mining. They’ve started mining one of the world’s most promising reserves of titanium ore. The CEO told me that this wouldn’t have been possible without climate change. The mining industry of Greenland is taking off. That’s a very complicated situation that the Greenlandic people are having to grapple with.

Qaanaaq, Greenland.

The chapter about the Democratic Republic of Congo relates to business and human rights, due diligence in supply chains, particularly on the back of the battery metals boom. Cobalt is one of those key minerals. You visited a region in DRC, Lualaba, at the centre of the cobalt rush. What are your takeaways from that trip?

Cobalt is a crucial mineral to the production of electric cars. Now, this is not an argument against electric cars, we need them. The point is that we have to ensure that a cleaner economic system is also a more just one.

I visited a Congolese city called Kolwezi, a residential area where people have started digging cobalt mines around their houses. I thought it was important to go down there to understand what people were putting themselves through.

The vast majority of the world’s cobalt comes from Congo. Most of it comes from mechanizedmines, but you have over 100,000 of artisanal miners, who work in very dangerous and tough conditions.

Monique Swila is one of tens of thousands drawn in by the cobalt mining rush in the town of Kolwezi, 300km northeast. In the residential district of Kasulo, teams of barefoot miners use hand tools to tunnel deep into the earth in search of crumbly black deposits of cobalt.

There are children’s playing all around the mine, is incredibly dangerous. It’s good that people are concerned about child labour in the Congolese mining industry. Of course, it’s an abomination and intolerable, but we should be thinking about the reasons why children are driven to work in mines in the first place.

To try and understand that I spoke to Richard Muyej. He’s one of the most powerful people in Congo. He’s the former interior minister. When I met him, he was the governor of Lualaba the province where most of the mining happens. He was very open about the corruption that has dogged this country, about what’s happening to the incredible wealth of a country like Congo, where so much of it is being syphoned off for the benefit of a few.

You have to blame the Congolese politicians. But also, the Western companies who are working with them very closely, and Chinese companies that are completely complicit in this system. I think with the move towards a cleaner energy system, we also have an opportunity to think much more broadly about developing an economy that is fairer, more inclusive, and simply more ethically run in general. I hope that’s something that we are going to see more focus on over the years to come.

Children playing in a residential area packed with informal cobalt mine shafts in a residential district of Kolwezi, southeaster DR Congo. The shaft to the left of shot is about 30 feet deep.

Let’s talk about the financial impact of biodiversity loss. There are two chapters about this topic: Maldives, built on a coral reef, and Brazil, where the Amazon is being devastated by illegal deforestation. Can you unpack these two chapters?

These are two ecosystems in crisis right now. Coral reefs are dying at an extraordinary pace, thanks to the rising temperature of the ocean as well as the increasing acidification. There are four countries in the world, including the Maldives, that are made up of coral islands. If sea levels continue to rise at this pace, they will disappear. It was a very surreal experience to go there and speak to people because they are continuing with their normal lives. What else are they supposed to do?

I spoke to Mohamed Nasheed, who is the former president of the Maldives. He became very famous, you might remember, around the Copenhagen conference in 2009 when he held a Cabinet meeting underwater with scuba gear to publicizethe danger that his country was in. It’s getting very serious. He’s really pinning his hopes on technological fixes that could save the coral, new forms of genetic modification. It will be a tragedy if that country is allowed to just disappear in its current form.

An aerial shot of Chinese-funded construction at Hulhumale, a new artificial island designed to be more resilient than the rest of the Maldives to rising sea levels.

In Brazil, you have a similarly worrying situation with the rainforest. I had a conversation near Sao Paulo with Brazil’s leading climate scientists, Carlos Nobre. He believes that we will reach a tipping point when the rainforest starts just shrinking under its own momentum. He estimates that comes with 20% destruction of the rainforest, now it’s 17%.

Under President Bolsonaro, a sense of impunity has been allowed to kick in. But there are people fighting back against illegal deforestation. Awapy, quite an inspiring young man, is a member of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau tribe. He leads a group of young people defending the forest community to push back against the invasion of their land Awapy’s brother-in-law, and fellow leader of this group, was murdered a few months before my visit to the region. It’s serious on the ground. I was inspired by what Awapy and his fellow young companions were doing to protect that forest. They need more support, not least from their own government.

Awapy, (left, with his friend Tebu), is a member of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau tribe in the southern Brazilian Amazon.

Some chapters of the book talk about moving cities elsewhere completely or rebuilding them to be resilient to climate change. For example, towns and cities in Solomon Islands, Ethiopia, Nigeria, as well as Venice. What can you tell us about this theme of liveable cities and climate finance?

Most of us live in cities and urban areas. The question of how cities respond to climate change is going to be absolutely core. You have groups of cities that are trying to collaborate and exchange best practice for this. I found Venice and Lagos very interesting

Venice, of course, is very vulnerable to sea level rise and to increasingly powerful storms in the Adriatic. When I was there, they had the very first full-scale trial of this new barrier system called MOSE It’s named after Moses, the divider of the seas.

I met Alberto Scotti who is now into his 70s. He was sort of the visionary who came up with the concept. He’s been working on this for decades. This was to be a barrier system that would be invisible, hidden beneath the sea. Then when a storm comes, the barriers go up. They didn’t want to ruin the beautiful aesthetic of Venice because tourism is so important to the economy.

But this was at the centre of one of Europe’s worst ever corruption scandals, huge amounts of money syphoned off by the political and business elites of Venice. This has inspired tremendous skepticism among a lot of people in Venice, about the whole MOSE system itself, saying it’s all just a racket, what happens when climate change is just being used by corrupt elites as a way to make money.

The first full-scale test of the multi-billion euro MOSE barrier designed to protect Venice from rising sea levels and storm surges.

Lagos is of course a very different city. Already one of the biggest, potentially the biggest, cities in the world. But very vulnerable to flooding. There’s this enormous new development, a vast new city that’s being built entirely on reclaimed land. It is protecting the commercial hub of the city from the sea. But further down the coastline there are people on lower incomes who are suffering the flip side of that, who are suffering from more serious erosion.

So often, as we’ve seen in recent decades, every major economic trend just seems to work to the relative advantage of the better off and the relative disadvantage of the worse off. Is this going to be the case with the global climate response? Is it all going to be skewed in favour of the better off? According to many people I met in Lagos that is the case in that city. It raises some important questions. I think that is relevant well beyond Nigeria.

Lukman Oladele beside what remains of his bar and guesthouse complex on Alpha Beach, to the east of Lagos. Alpha Beach used to be a thriving beach resort for middle-class Lagosians, but its beachfront tourist scene has been devastated by a series of powerful sea surges that have pushed the shoreline dozens of meters inland.

Carlos Martin Tornero is an Associate based in London.