The leading voice on sustainable finance speaks with Brunswick CEO Neal Wolin.

“The banker’s banker, the superstarbanker, the George Clooney of banking, possibly even the James Bond of banking”—that’s howThe Guardian characterized Mark Carney, whose career in finance has been so stellar that his formative 13 years at Goldman Sachs is treated as almost a footnote.

The Guardian’s praise for the former Governor of the Bank of England (and former Governor of the Bank of Canada) is, in fact, a reaction to his track record in handling crises, in particular his growing celebrity on the financial sector’s role in responding to climate change and stakeholder capitalism.

In such charged, complex issues, Carney’s views stand out for their clarity—“now is the time to ensure that every financial decision takes climate change into account”—and practicality. In 2015, while Governor of the Bank of England, Carney helped create the hugely influential TCFD (Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures), a framework designed to help investors better understand the climate risks associated with their investments. In June 2021, G7 nations—which account for about one-third of global GDP—agreed that, over the coming years, they will make it mandatory for companies to report against TCFD-informed frameworks, and at COP26, 45 countries backed the new International Sustainability Standards Board of the IFRS, which will create a global climate standard based on the TCFD.

Today Carney serves as the UN Special Envoy on Climate Action and Finance and Vice Chairman and Head of Impact Investing at Brookfield Asset Management, which manages more than $620 billion. In 2021, Carney, a 3:30 marathoner, added another title to his résumé: author. His book, Value(s): Building a Better World for All, opened a conversation with Brunswick CEO Neal Wolin.

Mark, you’ve written an extraordinary book in which you draw on your own experience in dealing with the great financial crisis, climate change and COVID-19 to argue that social values must be embedded in our sense of economic or market value. Could you build out that argument a little bit more?

Part of what I tried to do was think about some of the common links across those issues you mentioned, Neal, and draw out that relationship of value in the market and values of society. It’s a relationship that goes in both directions.

If I were to simplify the global financial crisis, it’s where we lost the values that underpin the market, like fairness and responsibility. We lost a sense of the systemic as well as a sense of self, so to speak. That undercut the functioning of the market. Of course, there were a series of technical problems, and we enacted a host of regulation afterward to address those, but those cultural underpinnings played a real role. The book goes back to what as an economist is almost first principles, the two legs of Adam Smith: the invisible hand ofThe Wealth of Nationsand also his theory of moral sentiments, the social conventions, that are necessary for the market.

That’s one direction in terms of the relationship. But then there’s the opportunity for the market to help us achieve society’s values. If we organize things properly, if we’re clear enough about what we want, we move into a world where we have a hierarchy of values. And then the market can be directed in order to address that.

And of course, in the middle you could say, is thinking about the purpose of companies (and other organizations, but let’s focus on companies for a moment). What’s the purpose of a company? What type of solution is it trying to provide? How does it organize? And if it truly has a purpose, how can it maximize the benefits for all stakeholders, including—very much including—shareholders? I try to draw out where that works and where it can fall short.

The debate about the role of business in society has become mainstream, so too the notion that businesses have to deliver social value alongside financial value. Where do you think the world stands on that question? Are we seeing mostly rhetoric, or a meaningful shift?

It’s real; that’s the short answer. You see these kinds of seismic shifts across history. Originally, you couldn’t have a corporation unless you had a purpose in your charter. That evolved to a point; many US companies are incorporated in Delaware, and they still have to have a purpose in the Delaware Charter. But you find that their purpose in that Charter is to respect all the laws of Delaware, which, I think you’d agree, isn’t a very profound one.

We obviously went through a multi-decade cycle of shareholder primacy. Now it has begun to rebalance toward stakeholders, this broader sense of community. I see a few things driving that. Society’s expectations are changing. People want identity, want to be working for a bigger cause. And that creates dynamic materiality. In other words, something that was not material to a company’s well-being or financial performance all of a sudden becomes material. You saw that with issues around climate change, around biodiversity, around diversity. Think of the impact of George Floyd’s tragic murder. The expectations, rightly, were raised, and the focus on those issues, and how companies responded, became hugely important.

There’s also the issue of performance. When you find purpose clearly defined—if you really mean your purpose, and that’s clear to your employees, suppliers and community—you actually get reinforcing actions that help you deliver it.

Shopify, for example, is headquartered down the road here in Ottawa. Their purpose is to drive entrepreneurship, to have a platform that makes it easy to be an entrepreneur. There’s a whole ecosystem that’s grown up around it (not all within Shopify) that makes it easier to onboard, to understand tax obligations, to make cross-border payments—all those aspects reinforce the flywheel of Shopify, they’re not just “corporate do-goodism,” as Friedman would have said.

So many of our clients are increasingly feeling the need to speak out and to act on societal challenges, not just on questions of climate or inequality or race. What’s your advice for CEOs who are thinking about when and how to use their voice in addressing societal issues so they can, as you talk about, connect that economic value with social value?

It’s one of the toughest decisions a CEO or a leader has to make. It starts with perspective. The nature of being a leader is that you’re a custodian of that organization. You’re trying to improve it; you’re trying to bring people along with you for the long term. And you have a better long-term perspective if you have a number of other perspectives: how your company is operating within the community, the views of the people in your organization, particularly those starting out or not yet in leadership roles. That can help guide you on when and when not to make a stand on an issue.

Leaders see most clearly when they see from the periphery. You have a very good sense of an organization if you’re working in one of the entry-level jobs, or you’re the most junior person in the meeting. As a central banker, we used to go around the UK and meet with disadvantaged groups. Now, the interest rate is a very blunt tool and affects the economy as a whole. But having a sense of the people behind the unemployment figures or the wealth inequality figures—that sense of the experience from the periphery is so important.

But let’s be clear, these are tough issues. Part of the reason they’re controversial is there’s strong feelings on all sides. And by standing up you’ve got to be confident it’s the right thing. But it doesn’t mean you’ll get universal accolades for doing so.

As inequalities rise within wealthy countries, they are also rising between low- and high-income countries. What’s it going to take to close those gaps?

We were going through a period, not universally, but a broader period of global convergence. Virtually all of the convergence we saw over the last 15, 20 years has been unwound with COVID.

Unfortunately, that’s likely being reinforced by the health inequalities around vaccination, to all of our detriment. There’s fundamentally a question of common humanity. But you can make it a very economic issue as well because COVID, as we all know, is not over anywhere until it’s over everywhere. That’s just being reinforced with current variants.

There will be more to come, and that will reinforce this divergence. Technological changes will also push in the direction of higher inequality for a period of time, however fundamentally empowering they are.

What can we do? I’m going to focus just domestically. There’s a whole set of things internationally that need be to be done, and a huge amount depends on the country. But there are certain policies that can, for instance, support equality generally and equality in work. In the US, you’re talking about childcare, family support. We have a similar issue in Canada around universal daycare. Now, if you’re in Sweden or France, universal childcare is not news. Those things help improve participation in the labor force and address overall family inequality.

Every day I’m confronted with further evidence that this is just an enormous commercial opportunity.

There are also basic things around true universal broadband. Mentioning “universal broadband” is like saying “skills training”—it’s something everyone says but nobody ever really does. But it’s absolutely fundamental. As if we needed evidence of that, the tragedy of education under COVID has just reinforced it.

More optimistically, in a world where distributed labor is much more possible, there are better leveling up opportunities, ways to distribute higher-value jobs regionally.

There is also, by the way, a big, big question globally of the extent to which you allow outsourcing across borders because price equalization could push wage inequalities within countries much higher.

Ensuring people can be in the labor force, that they have skills, access to the broadband system, distributed work opportunities—these are all components of it. And then very importantly, in a series of countries, the energy transition has to be very deliberately handled in a way that’s going to support regional solidarity to counterbalance some quite considerable forces of inequality that could come along.

It really needs to be an obsession. No simple policy prescription can address this. Some people posit universal basic income, but I don’t think simply ticking that very expensive box can suggest it’s been addressed.

In trying to raise the world’s understanding of the financial risk of climate change, you’ve begun to talk more about the transition as the greatest commercial opportunity of our time. How do you think about the conversation moving more in the direction of opportunity—for the financial sector, for the broader private sector—as an important component of getting to where we need to be?

Let’s tie a few things together. Years ago, I helped come up with this idea of “the tragedy of the horizon,” which is, essentially, if we could see far enough into the future, we’d act today. If we wait to act until the physical risks are so manifest and painfully obvious, then there are going to be wholesale assets stranded, there are going to be very sharp adjustments in the economy, especially to the financial sector. It would be much, much less expensive to start now. That’s the tragedy.

You and I opened the conversation discussing this relationship between value in the market and values of society. And what’s been happening in recent years, which ties back into stakeholder capitalism and the purpose of companies, is a greater emphasis on dealing with climate change. It really has accelerated over the last 18 months or so. You see it in social movements. You see it in voting patterns. Governments act with a lag, but you’re increasingly seeing it in government policy, these net-zero commitments.

Now you bring those together and all of a sudden there’s a possibility of addressing this risk, of us actually breaking the tragedy of the horizon. Well, at 30,000 feet, if you turn an existential risk—which is what climate change is—if you solve that, you’ve created tremendous value. If that’s what society wants you to do, you create enormous value.

This is an issue that, in general, investors, lenders and competitors have not looked at except in the extreme. At first it was mostly the energy sector. People looked at coal versus renewables or heavy oil versus solar, but now they’re comparing two consumer goods companies or tech companies or heavy industrials. They’re seeing who has better prospects, who has worse prospects, who has big investment needs, who might get left on the wayside. It’s now tied to lofty values likes resilience and sustainability. All of that drives big, big differences in value and value creation.

It’s an enormous commercial opportunity and we’re starting to see capital shift. I increasingly hear the argument that this is the internet in the mid-1990s, where you’re just on the cusp of understanding that there’s going to be a wholesale rewiring of the economy for sustainability—that scale of change.

You can anticipate a series of initial opportunities. But it’s such an order of magnitude. It’s so fundamental that there will be new solutions that come up, huge business-process re-engineering that will come along with it, and tremendous and exciting opportunities as a consequence. Every day I’m confronted with further evidence that this is just an enormous commercial opportunity.

Did COP26 accomplish what you hoped it would?

COP26 was a watershed moment. Many of the world’s largest banks, insurers, asset managers and pension funds stepped up to finance the enormous investments needed to transition the global economy to net zero. GFANZ (the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero) made rapid progress, bringing together in only a few short months a coalition of over 450 financial institutions—spanning the waterfront of global finance—who committed to aligning their balance sheets with achieving net zero and limiting the temperature rise to 1.5 degrees.

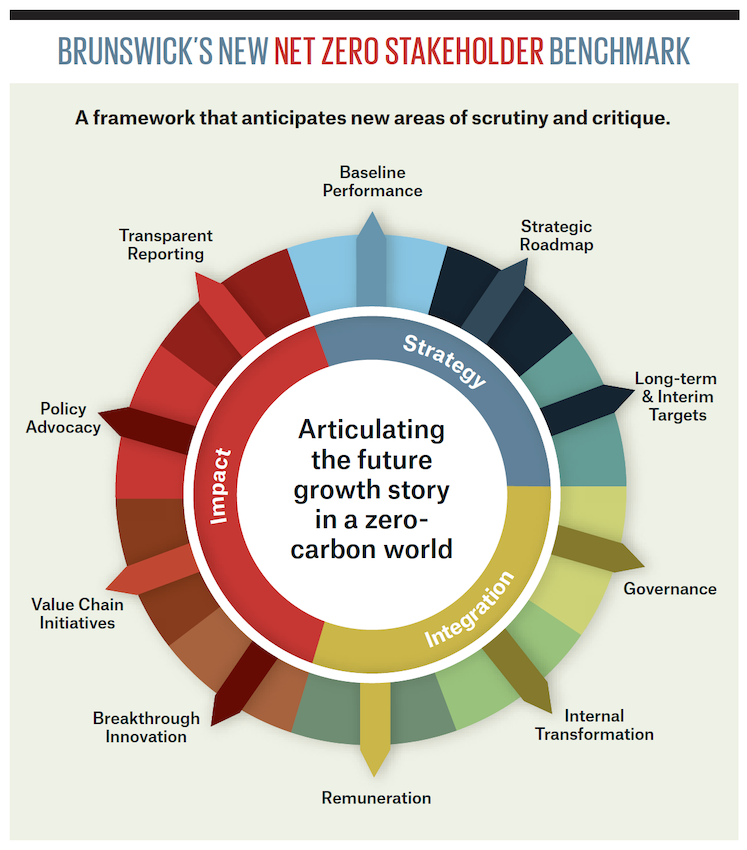

But, of course, there is more to be done. COP26 should be seen as a launchpad. In 2022, we’re rolling up our sleeves to turn commitments into action. The focus of all stakeholders will be making meaningful and credible progress on the net-zero commitments made at COP26 including the mobilization of significant capital to emerging markets and developing countries. We will be saying more about the priorities for GFANZ in the coming months, as we approach our one-year anniversary.

You’ve led a coalition that’s committed to aligning over $130 trillion of private capital to delivering net zero, along the way winning a lot of praise, but there has also been some skepticism. What would you say to those who are skeptical toward commitments and demand action?

I understand the skepticism. After all, if governments didn’t follow through after COP21 in Paris six years ago, why should private financial institutions this time? Public and media scrutiny are welcome because they help distinguish what is credible and science-based from corporate greenwashing. GFANZ members are required to use the most rigorous, science-based pathways, grounded in the UN’s Race to Zero. In addition to net-zero emissions by 2050, GFANZ members have also committed to their fair share of 50% greenhouse gas emissions reductions by 2030 and, within 18 months of joining, banks must set out detailed transition plans. These sector-specific plans will show the hard numbers. Emissions can’t be greenwashed. The numbers will either go up or down—and companies will be judged accordingly.

Is inflation your primary concern about the global economy?

I’m too much a central banker to ever deny that inflation is a primary concern. But it is joined by the need to translate commitments into actions, not just for the climate and future generations, but also for current growth and jobs. Climate policy is a new pillar of macro policy, and credible and predictable climate policies, when combined with the new net-zero financial system, will drive investment and growth across our economies.

More from this issue

The S in ESG

Most read from this issue

The Standard for Corporate Climate Action