Africell turned the unlikeliest subject—a contentious infrastructure project—into a feature-length film streaming on Apple TV and Amazon Prime Video. By Sam Williams

The convoy stopped at dusk somewhere in the middle of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). One of the cars had sprung a leak. The next town was three hours ahead through empty bush on cratered roads. Behind us, an hour back, local kids had warned about bandits and rebels who “kill people in strange ways” in these parts.

As night neared and we stood wondering what to do, someone noticed it: a railway sleeper, half-buried in elephant grass, barely visible. The track ran straight in both directions, carving a line through the wilderness. The railway had been laid over a century ago and cost countless lives in the process. For the past 50 years it had mostly sat silent, its bridges blown up, its periphery mined, vines slowly strangling the rails.

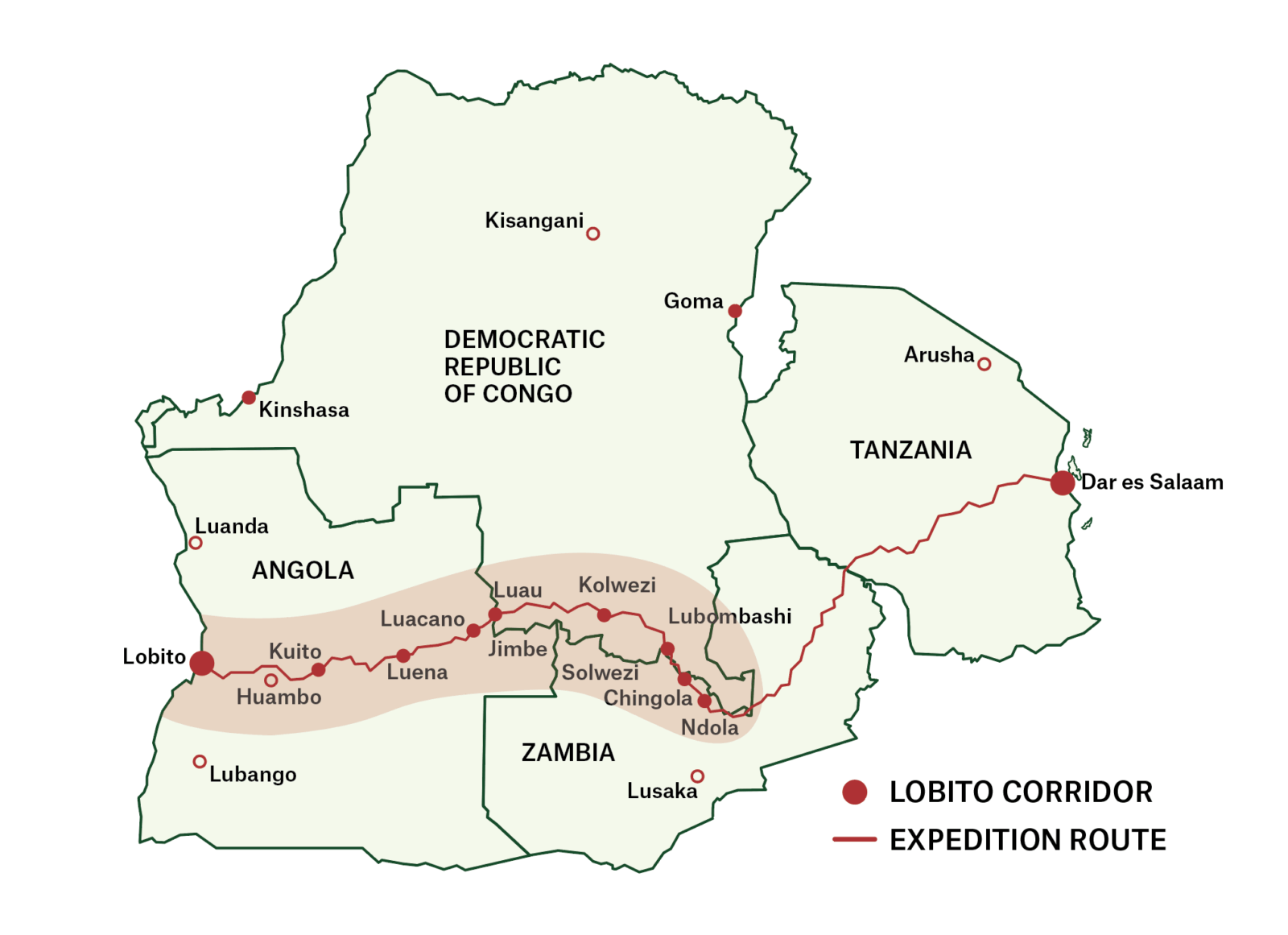

This is the Lobito Corridor, the railway meant to connect central Africa’s copper belt to Angola’s Atlantic coast, and the subject of Africell’s feature-length documentary Lobito Bound, a film that would eventually stream worldwide on Apple TV and Amazon Prime Video.

Africell is a mobile network operator, not a railway company. But in the Lobito Corridor we saw a mission like the one that drives our business: creating connection. Rather than producing reports no one would read, we wanted to get people to pay attention to a project in a part of the world that is too often overlooked, but which we call home.

The railway to Lobito had been a source of hope and disappointment since it was first conceived by an eccentric Scottish tycoon in the late 19th century. With the assent of Angola’s Portuguese colonial authorities, it had been built to haul Congolese minerals west to European foundries and factories. Angola’s civil war in the 1970s, which killed as many as a million people, shut the railway down. China tried to revive it in the 2000s, though progress stalled. Now the US and EU are investing billions to rebuild the railway and help safeguard its access to copper, cobalt, coltan (and a bewildering array of unpronounceable “rare earths”) while also creating jobs and infrastructure in one of the world’s poorest and most troubled regions.

In June 2024, Africell set out on a 4,000-km filmmaking expedition to discover what that promise actually means to the people of the region. From Tanzania’s Indian Ocean coast to Angola’s Atlantic shore, Dwayne Fields—a Jamaican-born British explorer who traces his ancestry back to Central Africa’s Copperbelt region—spoke with senior officials and investors. But he also sought out voices that are typically absent from discussions of policy and infrastructure.

In Kitwe, Zambia, Fields walked through a township with Chomba Nkosha, a miner turned comedian. They wandered through streets that once had cinema halls, sports fields and community centers—all sold off now. “When I go back in time and see what we had then and look at now,” Chomba said, “sometimes I feel like crying. It’s like a war zone.” He hopes new investment might restore what was lost, though he’s wary.

Outside Kolwezi in DRC, Fields descended 200 meters into Kamoa-Kakula, one of the world’s largest copper mines, where almost 1,000 people work underground each shift extracting minerals that might end up in smartphones, electric cars, wind turbines, data centers or ballistic missiles. The mine already plans its own railway spur, anticipating the extension of the corridor. Fifty thousand tons of copper leave this site every month, on trucks that can take 10 days to cross a border.

Angola is one of the most heavily mined countries in the world. In its highlands, where the air is thin and light blinding, Fields walked into a minefield with the HALO Trust, an NGO that clears the debris of war. Seb Haddock, the unit commander, showed Fields a waterfall that should be a major tourist attraction but is empty because it can’t be reached safely.

On the Swahili coast at the beginning of the journey, Tanzanian journalist Elsie Eyakuze told Fields that Africa too often feels like “the grass beneath clashing elephants,” that is, like a land caught between great powers competing for resources. “If it doesn’t go well,” she said of the Lobito Corridor, “then maybe it’s just the carving up Africa all over again.”

In Angola, explorer and presenter Dwayne Fields walked through a minefield with Seb Haddock from the HALO Trust (left), and visited a picturesque waterfall that is unsafe for tourists (center). Fields, at right in a brown shirt, with then-US Ambassador Tulinabo Mushingi, beside one of the SUVs that carried him and an Africell team across much of the width of Africa.

At the journey’s end in Lobito, then-US Ambassador Tulinabo Mushingi described the project as “win-win”: supply chain security for America, jobs and infrastructure for Africa. When Fields asked when ordinary people would benefit, Mushingi said, “As soon as their mother can come and sell something quickly, as soon as health wagons stop and people can come and see a doctor, that’s when they will start to see.”

If a theme emerges in Lobito Bound, it is that of hard-bitten hope. Those living along the Lobito Corridor aren’t betting too much on the success of a project that may be hostage to changing administrations, shifting priorities and volatile funding. But they do believe that, unlike in earlier times, more Africans stand to gain from it if it does come good.

“It has been hard to ignore the echoes of an age-old story,” Fields says in the film’s final shot, squinting against the fierce tropical sun. “It’s a story of outsiders looking to exploit this continent for its enormous wealth. But this version does feel different. On my journey, I’ve met Africans working hard to make this story their own. And I’ve met many more who are excited about the opportunities to come.”

Fields gazes out to sea. Tankers and container ships wait along the horizon for a berth. It is unclear whether those ships are bringing things in or taking them away. “I don’t think any of these people know for sure whether they believe in the Lobito Corridor or not,” he says. “I don’t think that matters. They are just hoping it works.”

Sam Williams is Africell’s Group Communications Director and the executive producer of Lobito Bound. He worked for Brunswick in London and Abu Dhabi between 2015 and 2020.