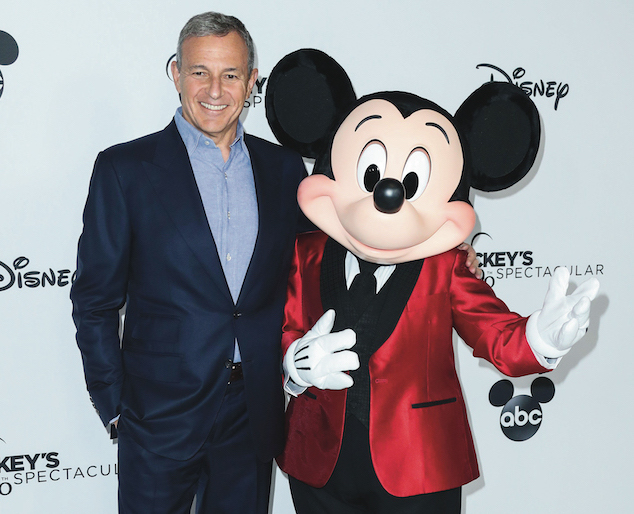

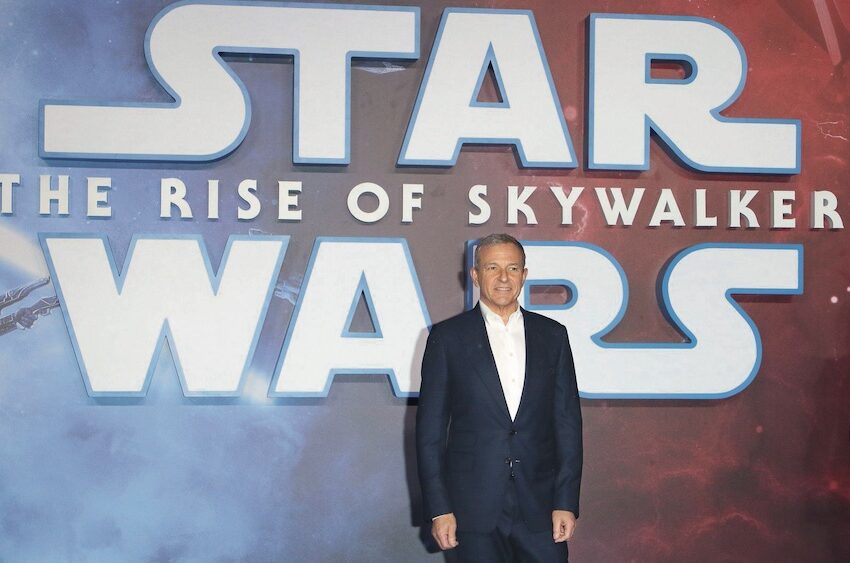

Brunswick founder Sir Alan Parker speaks with Executive Chairman and former CEO of Disney.

After news broke in late February 2020 that Bob Iger was stepping down as CEO of Disney, Walter Isaacson, the formerTime editor and author of a mega-bestselling biography of Steve Jobs, appeared on CNBC to talk about Iger’s legacy. “It’s huge,” Isaacson said, “he’s one of the great CEOs of our day and generation. He has been able to do the essence of value creating in the digital revolution, which is to connect imagination to technology.”

Like many content creators, Disney could have been left in the dust of new players like Netflix. But during Iger’s 15 years at the helm, the company’s share price quintupled and its annual income quadrupled as it became one of the world’s largest and most forward-thinking media companies. Iger emerged also as perhaps the greatest dealmaker of his generation. He orchestrated a string of acquisitions—Pixar, Marvel, Lucasfilm, 21st Century Fox—whose audacity was seemingly matched only by their rate of success. He also opened a Disneyland in Shanghai in 2016—an achievement that, given its geopolitical and logistical complexity, Iger described in his memoir,Ride of a Lifetime, as “the biggest accomplishment of my career.”

Iger, who now serves as Disney’s Executive Chairman, spoke with Brunswick Chairman and founder Sir Alan Parker at the firm’s virtual Annual Partners Meeting. As the pair discussed Iger’s book, it emerged he was in the process of thinking through a new one. “It’s about leadership in a crisis, and I’m constructing it right now with somewhat casual notes,” Iger said. “But I think I’m going to ultimately write it.”

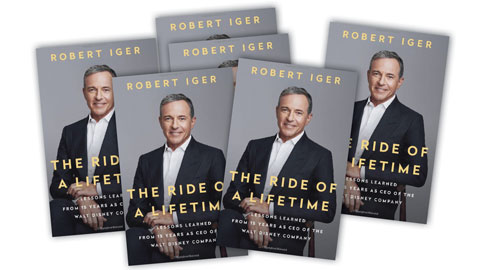

We sent your book, Bob, to everyone in the firm, and many, many folks had already read it. This book’s been an amazing success—a No. 1 New York Times best seller. You must be pleased.

I am. Thank you very much. I’m donating all the proceeds to create scholarships for journalism students aimed at fostering more diversity. So it’s for a good cause.

I’m pleasantly surprised that it has resonated so well with people in business and people who want to be in business. It’s a pleasant late-in-life surprise. Given all the angst I had about writing it, it’s a relief.

More than anything, what people have reacted to is the fact that it sounds like it’s in my voice, which is very true. It was my computer, or my typewriter, or my pen, however you want to put it. That’s one of the reasons it resonated. Also I think it’s pretty digestible. Since I’m professionally a storyteller, my aim was to tell stories. I haven’t read that many business books. Not that they’re not of value, but often they can be really dry. And I didn’t want to write just another dry business book. So my aim was to tell stories, and teach some lessons along the way.

It’s quite fun in that you write not only about leadership, but also how to get to a position of leadership.

I must say I was self-conscious talking about leadership. I feel that’s not something a person’s allowed to do until they’ve actually demonstrated they have some leadership abilities. And I was very, very careful about that. Even the leadership tenets that I listed, I wanted to see whether I could check boxes in terms of my own leadership performance.

The book was written mostly not because I felt that I had a great story to tell, but because I thought in telling my story I could teach some lessons to people. I’m asked interesting questions and somewhat absurd questions—“Who’s your favorite Disney character?” But one I’m always asked is, “What’s the secret to your success?”

“I didn’t want to write just another dry business book… Since I’m professionally a storyteller, my aim was to tell stories.”

When we’ve talked before, you’ve raised this point about the duality of leadership: You want freedom for the creatives, but you want them to operate within a system of values. You want to focus on the big picture, but you’re passionate about the detail. How do you think about that?

You have to create a balance. One thing you just touched upon, for instance, is the balance between operational excellence and long-term strategy. You have to have a foot planted firmly in the present that’s operating your business for today, and you have to have a foot in the future trying to figure out, “Where might the business go?”

I realized in terms of how I allocate my time that it was incredibly important to demand operational excellence for all kinds of reasons, including the investment community. But it was incredibly important—and this is what a CEO must do—to lead the company into the future.

It’s one of the three key or core responsibilities of a CEO. One is to define what the organization is, what the company is. In our case, it was mostly high-quality branded entertainment. Secondly, define or determine the direction. That’s strategy. And then of course the third: What is the value system? It’s those three things. And all of those must emanate from the CEO of the company.

How can a CEO be that kind of “futurist”?

I see it as trying to paint scenarios or create potential outcomes about what the future specifically might be for our company. It’s an area where I tried to set an example—I constantly articulated those ideas about what the future looked like to the most critical people on my team. And I exhorted them to think in a similar way. You know, “Let’s talk about what might happen in our businesses down the road, and if we believe in these scenarios, then what do we need to do and when to be successful in that new world?”

Look, the pace of change is crazy. It’s the fastest we’ve ever seen. If executives cannot live in a world of change, if they aren’t capable of being futurists, then they shouldn’t be working for you. I’ve found an executive who lacks those capabilities is unlikely to be much use to you down the road.

To me Disney is so magical because of the nostalgia it carries. What does that responsibility feel like when you’re putting out content as Disney, knowing how powerful it can be in influencing a generation’s imagination and memories?

I’ve always been aware of the impact we have on the world. It does put more pressure on us to be right and to be good. And that’s really hard. Particularly in today’s world which is so polarized and there’s so much disagreement about what is right, there’s pressure to compromise standards or to please everybody. You can’t do that.

So you have to have an ability to say, “What are the things we want to stand for? What do we believe is important?” And then you have to execute against those standards without compromising to those people who just do not believe that what you’re doing is right to them.

That’s required us to do a lot of things. We’ve had to diversify more. Not only in the people that are creating content for us and telling stories, but also those that are managing the storytellers at the company. We’ve learned that the only way to get things right is to have the voices in the room be from diverse, different backgrounds.

We also had to look back at all the things that we’ve done in different times and different standards and sometimes realize that in today’s world they’re not acceptable any more. We just have to do what we believe is the right thing and then move forward and make sure that we don’t follow the same path today, that we’re much more responsible in how we tell stories and the stories we tell because we’re more inclusive.

But the bar is high. Really high.

“Work, curiosity, luck. You put those three things together, and you get the odyssey that I had.”

When I mentioned to someone that I was speaking to you later, they said, “Oh, you mean the greatest dealmaker of our generation?” I know with your humility you’ll hate that. But you do deals. What motivated that approach?

I won’t be humble in this regard. When I became CEO in 2005, I really had to think about what the company would look like down the road. That meant asking, “What steps do we need to start taking to be successful long term?” I concluded that content was king and that technology was going to commoditize distribution. Meaning there would be cable, satellite and internet. We weren’t really thinking of an app-based media and entertainment business or consumption. But my sense was I shouldn’t be focusing on that because distribution opportunities and consumption opportunities were going to proliferate.

So let’s not invest in that commodity but let’s take advantage of it. And how do you take advantage of it? Well, you create great content to feed this voracious appetite that technology has created. And the interesting thing about most of this technology is we’re not even investing our own capital in it.

I think it was Charlie Munger from Berkshire Hathaway who asked: “What happened to Coca-Cola when someone invented the refrigerated vending machine for carbonated beverages?” Now, maybe Coke had a hand in it. I don’t know. But suddenly, you could buy a Coke on any street corner, and it was cold, so it was better to taste. And boom. So the world is a cold carbonated beverage dispenser (laughs), and Disney’s the beverage.

That’s what begat Pixar, Marvel, Star Wars, National Geographic, ESPN—quality brands. Invest in quality content. Although I will say another new dynamic is scale on the content side: so quality and then scale of quality. In order to compete for the consumer, you have to have scale. You have to have a lot of stuff that they’re going to want.

Where do you see the sector’s trend line going?

You’re going to see continued consolidation. Lots of it. And fast, because of that need for quality and scale.

I bet every boardroom, whether they’re distributors or platforms, or whether they’re content companies who had not been part of consolidation, are thinking, “OK, what can we buy? What’s out there? What can we do? What can we sell?” The marketplace has gotten a lot more competitive.

One of your other passions that I can’t resist touching on is quality journalism. You have a passion for quality journalism, as does your wife.

Yes. Well, I did some work for ABC News back in the early, early days of my career. And I worked for a man named Roone Arledge, who then became president of ABC News and then worked for me as well. And he was a real mentor of mine.

I got steeped in network television journalism and I just loved it. I loved the adrenaline rush, the sense of purpose, the urgency, the immediacy, the relevance of it. When you’re in news, you’re relevant every day.

And I’ve been close to the ABC News operation really since the late ’70s. Coincidentally, my wife, who was a journalist, is now the dean of the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism at the University of Southern California. And it’s so interesting to watch someone create a whole new curriculum, to think through the question of “What is great journalism today?” For years they were teaching students to practice journalism mostly for print media. And while that’s not completely obsolete, it’s obviously just one part of their craft.

So yes, it’s very much a passion of our household. When you look at the world today, one of the things to worry about is the future of freedom of the press worldwide. And standards as well. Standards of honesty and integrity and impartiality. Getting it right in a world where everybody wants you to get it fast is really complicated.

Iger at a 2018 premiere of “Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker.” Six years earlier, he had orchestrated a deal to buy Lucasfilm, the company behind the Star Wars movies, for $4 billion. Wired magazine later called it “the deal of the century.”

Rereading your book, Bob, it really struck me how much of an adventure story it is. A young man with bags of talents and ambition, plus a tremendous work ethic. But it’s not as if you knew where you were going.

I think it was in Steve Jobs’ commencement speech at Stanford when he talked about connecting the dots. It’s always easy to connect the dots looking backwards. It’s not as easy going forward. You know, you touched upon three things that are really critical in terms of my success.

One is work ethic. I just had a voracious work ethic. I love work. Second, curiosity. I give my mother and especially my father tremendous credit for that. I think you’re probably born with a curiosity gene. But then someone has to let you know it’s there or teach you how to tap into it and exhort you to continue to do so, and my father did that for me.

And the third, of course, is luck. So work, curiosity, luck. You put those three things together, and you get the odyssey that I had. I discovered early on, thank the good Lord, that I could outwork anybody. And that was interesting because I was not all that confident in my abilities. I had enough. I didn’t doubt myself. But I didn’t think I was special until I discovered that my work ethic was special and by outworking everybody I made up for what I consider to be an average set of abilities. And then the fact that I always wanted to learn, I always wanted to do new things, served me extremely well because in a way that drives you forward to new places. Tremendous, tremendous power in curiosity. More than I think anybody appreciates.

And then you just have to get lucky. I detail some of these moments in the book. I worked on a Frank Sinatra concert. Just happened to be produced by the guy who was president of ABC Sports. When it was done, he said, “Why don’t you come over and work for us at ABC Sports?” That led to a 13-year career that enabled me to travel the world in the pursuit of what we call the human drama of athletic competition. And that made me a much more worldly person and taught me a tremendous amount about production and storytelling.

I had bosses retire just at the time that I was ready to go to the next level—that happened two or three times. Then, of course, ABC was bought by Disney. I wouldn’t have run Disney if they didn’t buy us. It’s interesting to look back on it all because it seems like it’s a straight line, but it wasn’t.

More from this issue

Leadership

Most read from this issue

Chairman of the Board: Enrique Hernandez Jr.