That’s the pace the Girl Scouts of the USA aims to hold, says CEO Bonnie Barczykowski. “And if you’ve ever been around a 5-year-old, she runs fast.”

While interviewing to join her local Girl Scout council board in 2010, Bonnie Barczykowski admitted she “didn’t know anything” about Girl Scouts—except that they sold cookies.

That outside perspective, coupled with her leadership experience within one of the largest chains of fitness centers for women in the world, was exactly what the board was looking for, and so Barczykowski was invited to join.

She became COO of the Girl Scouts of Eastern Missouri in 2012, CEO of that same group a year later, and in 2023 was asked to lead the entire Girl Scouts of the USA organization.

As CEO, Barczykowski directs an organization with nearly 2 million members across the US and the world. Founded in 1912, the organization still holds to its original mission: “to build girls of courage, confidence, and character, who make the world a better place.” What has changed drastically, even in the 14 years Barczykowski has been with the Girl Scouts, is their approach to fulfilling that mission.

“I’ll hear a mom say, ‘That’s not the Girl Scouts I remember being in.’ And I think: ‘Nor should it be.’” In addition to selling cookies and earning badges, today’s Girl Scouts can try their hand at hundreds of activities: community service, code-writing marathons (known as “hackathons”), public speaking, horse riding, reading groups and the study, collection and release of live bugs.

“For us, it’s all about sparking that interest, because girls can dabble in so many things,” says Barczykowski. “The child psychologist Angela Duckworth talks a lot about the importance of ‘sampling before you specialize.’ There is no other organization that gives girls the opportunity to sample things more than Girl Scouting. What the girls learn through all those experiences—problem-solving, team building, creative thinking, having the courage to try things you otherwise wouldn’t—those help no matter what they choose to do in life.”

Both anecdotes and data support Barczykowski’s claim. Roughly 20% of female CEOs in the Fortune 500 today are Girl Scout alums, while 50% of women governors in the US are. “For me, success is: ‘Am I doing something that I can thrive in?’ And in that sense, you’re more likely to be successful when you’ve been exposed to a variety of things and explored where you passions and skills overlap.”

Offering that variety—in a way that manages to be relevant and fun—requires the Girl Scouts organization to constantly adapt. “We used to say: ‘We’ve got to run at the speed of a girl,’” says Barczykowski. “And if you’ve been around a 5-year-old, she runs fast.”

The very same might be said of Barczykowski herself, who after finishing more than 70 half marathons, (including one in Antartica!), decided to train for a full and since 2019, has completed eight full marathons.

When she sat down with Brunswick Partner Katharine Crallé (a Girl Scout alum), Barczykowski, who’s in her late 50s, shared she’s in the process of training for another marathon in November—one that will take place in Savannah, Georgia, the birthplace of Girl Scouts.

“Roughly 20% of women CEOs in the Fortune 500 today are Girl Scout alums, while 50% of women governors in the US are.“

From never being a Girl Scout to becoming CEO of the Girl Scouts—that’s quite a journey.

After I was invited to join a local Girl Scout board, I just fell hook, line and sinker. And I kept thinking: “How did I not know that Girl Scouts did all of this?”

Now, bless her heart, I spent a lot of time with my mom asking her why she didn’t sign us up for the Girl Scouts. I remember my twin sister and I begging to join; so many of our friends at our elementary school were Girl Scouts. And her answers, I think give a sense of why I’m so passionate about this role and what I’m focused on—because the biggest obstacles for her remain obstacles today.

Her first reason was: “I didn’t know enough about it. It felt like a secret club. All the girls at your school who were Girl Scouts, their moms had been, many of their grandmothers had been.” So I want to make sure that every young girl feels that she is welcome and she belongs—and so does the adult in their life. Had my mom felt like she could have belonged, my sister and I could have belonged.

The second piece of it was that my mom worked part-time at a grocery store, and my dad worked on an assembly line putting lightbulbs together. Girl Scouting was affordable back then, and it’s still affordable now, but it all depends on what people think of as affordable—it didn’t fit in my parents’ budget and they would have never asked for help. And that’s certainly still true today: Even though people know this could help their daughter, for a variety of reasons not everyone feels comfortable asking for assistance.

What I’ve learned from working in my local council, and what I so desperately want to help happen nationally, is that you can overcome both of those obstacles.

But how can you help people who won’t accept assistance?

I worked with a superintendent of a school district in a very rural community in Northern Missouri where only one of the three schools had Girl Scout troops. And the reason was that many families couldn’t afford a national membership. The superintendent said, “Bonnie, you can tell them you offer financial assistance, but they would rather explain to their daughters why they can’t, than to say yes to the financial assistance that you would offer.”

This just felt so wrong. So we went to a local utility company that had publicly talked about its desire to diversify and get more women in their workforce. We asked them if they wanted to invest in that commitment and help us give young girls skills. And they stepped up and made it possible for every single girl in the whole school district that wanted to be a Girl Scout to do so. No family had to raise their hand. It was amazing.

But when we were visiting the girls and the families, a young girl said to me, “I want to be a real Girl Scout.” I asked what she meant by that, and she said that real Girl Scouts had sashes, badges.

We went back to the utility company, which had paid for these girls’ $25 membership dues, and we asked them: “Can you help make her—and everyone in the district—a ‘real’ Girl Scout?” And they stepped up again: they covered the sash, the badges, the curriculum.

So, yes, the obstacles are real, but there are ways to overcome them. But you don’t overcome them with blanket decisions. For each community, it really is different.

We see in some of our school districts, for instance, that once girls go home from school, they’re either babysitting or have work they’re doing—I couldn’t tell you the number of young girls I’ve met who feed dinner to their smaller siblings. And in those cases, you see principals and superintendents help local councils find a way to meet during the school day. Because for those girls, if Girl Scouting doesn’t happen in school, then it won’t happen at all.

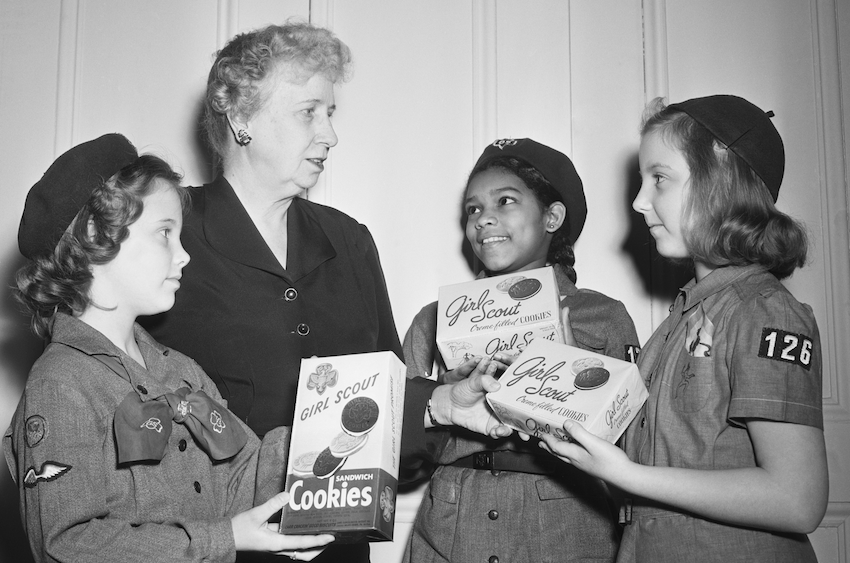

In 1951, US First Lady Bess Truman accepts the first box of Girl Scout cookies to open the cookie sale season.

What’s another challenge Girl Scouts face that people might be surprised to learn about?

Volunteerism in the United States—and actually in the world—has changed dramatically. When I think back to what I’ve read about when Girl Scouting got started in 1912, and as it expanded across the nation, you had so many adults who wanted to be troop leaders, to be mentors, and embraced it as almost a part-time job.

Today, volunteerism is our number one obstacle when it comes to lifting up and starting new troops. Most of our troop leaders today work full-time, so their ability to volunteer is very different. I see it in my own daughters—my oldest daughter has two little girls, they’re two and four. And she said to me, “Mom, if the Girl Scout Experience Box is still around when Nora goes into kindergarten, I’ll be a troop leader. If not, I can’t.”

What’s the Girl Scout Experience Box?

The Girl Scout Experience Box is our way to make sure we can provide all the tools that a Daisy troop leader needs—a step-by-step guide—and it lands on her doorstep every month. So she can deliver two troop meetings a month and have everything she needs. We piloted it last year, it was an enormous success, and so in August it launches for all Daisy troops in the country.

We know our volunteers want to be with their girls, they want to be that mentoring adult. They just can’t do all the shopping, collecting, planning. And it’s also good for the girls. In the past, if your leader didn’t like STEM activities, the girls may never have done STEM. But now they will.

Girl Scouts can earn so many different badges—cybersecurity, goal setting, automotive, and on and on. Is the theory behind that to get girls to try different areas?

Yes. And while those experiences look different today than what they were even a decade ago, that variety has always been part of the Girl Scouts. What Juliette Gordon Low [Girl Scouts founder] was offering girls and young women back in 1912, before women had the right to vote, was radical. One of the first badges that Girl Scouts could earn was an electrician. The acronym STEM didn’t exist then, but if you went back through all the badges, I’d venture to say many of them would fall under that label.

If you talk to an alum, what they often remember is that variety, and they’ll connect what they’re doing today with experiences they had as a Girl Scout. That variety can help girls uncover talents they didn’t even realize they have.

There was a Girl Scout troop doing a Hackathon, for instance, where they were working with interns on coding. These girls had to go through all these steps, from a level zero to a level 20. And there was this one young girl who was already at level 17, while others were starting at four or five. She came into it with no prior knowledge, and walked out of there knowing that this was not only an area she liked, but she was good at it. And you just have to wonder: Would she have ever known how good she is at coding if she hadn’t had that experience?

I could go on. We had a young woman who grew up in Washington, Missouri, a very rural community. She attended one of our STEM programs at a community college, and ended up taking and building a wind turbine out of recycled materials that powered a portion of her family’s home. She won a national award that we give at the Girl Scouts. And now she’s a mechanical engineer in Columbus, Ohio, with a Ph.D. And she told me: “I love my family, I love my community, I love my school, but this was all Girl Scouts—I would have never known options like this existed.”

I’ve got to ask about the cookies.

The first Girl Scout cookies were sold in 1917. And the program has always been about entrepreneurship and learning skills: goal setting, decision-making, business ethics, people skills.

When you talk to alums about the experiences they got from selling cookies, so often they’ll say, “It was the first time I actually had approached somebody and got rejected.” Not everybody that walks out of the grocery store buys cookies from you. You learn how to handle rejection, how to respond to it.

Now there’s obviously a digital side of it today—a girl creates her own mini website, videos, things like that. They’re incredibly creative.

I like that you have an option to donate boxes now, so I can feel like I’m doing my part, but I also don’t have the temptation of all those cookies at my house.

That’s what you call a win-win.

And talk about a sales technique—our girls know that if you say, “Oh no, I don’t need them around,” they’ll say, “It would be great if you could donate it to our troops or to the food pantry.”

We’ve had folks at the local council say to these girls: “Could I hire you to come work for us already?” They would see the girls’ marketing plans, budgets, how they had everything lined up… They’re remarkable.

Do all the attention that badges and cookies receive create a misperception about what Girls Scouts do?

You hear folks say: “Oh, Girl Scouts—that’s cookies and crafts and camp.” And my answer’s always: “Yes, and so much more.”

We do cookies, crafts and camps—and there’s coding and mechanical engineering and financial literacy. Our girls might go to an event where we’ve partnered with CISA [Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency]. And of course there’s team building, intentional time together.

There’s so much research out of the pandemic that families desperately want their girls to have supportive peer groups. Today our kids are surrounded with technology, and it’s never been easier to be isolated—to go from the TV in your room to your phone.

What I took for granted back when I was a kid is you just automatically spent time outdoors, spent time with friends—that just happened naturally. Now it doesn’t. You’ve got to be intentional about making time outdoors, time mentoring. You have to help make it happen. And we are the right organization to help families do that.

I feel such a responsibility for the Girl Scouts to be there for these girls in the way they need now—because you don’t get to go through these years again. There are 25 million girls in the US in kindergarten through 12th grade, and I really believe we can help each and every one of them. So we still have 23.9 million girls to go.

Troop 6000

In 2017, a new kind of Girl Scout troop launched in New York: one for families living in temporary housing. “Each week, Girl Scouts meet in shelters across the city to take part in activities that help them make new friends, earn badges, and learn to see themselves as leaders,” reads one description of the program. “All fees, uniforms, trips, and program materials are provided at no cost.”

In 2018, the Girl Scouts established the Troop 6000 Transition Initiative, which supports the girls as their families transition to permanent housing and works to help them stay connected to the community and the opportunities.

What started as a troop of seven Girl Scouts in Queens, Troop 6000 continues to grow and has served over 2,500 girls and women across 20 different shelters.

More from this issue

Transformation

Most read from this issue

In Conversation: Salman Amin