In Galapagos, former corporate executive Ambre Tanty-Lamothe is making it her mission to grow biodiversity in the boardroom. By Carlton Wilkinson.

The Galapagos Islands are one of the few areas where whale sharks, the world’s largest fish, can be regularly seen by divers as photographed above.

—

Ambre Tanty-Lamothe first saw the Galapagos Islands the same way most people do: as a tourist. An avid scuba diver, she went there to explore the area’s renown undersea wildlife.

“Just the sheer amount of fish, of sharks—the highest biomass apparently of sharks on Earth is in that spot,” she says. On land and sea, the experience of Galapagos is often described as being thrown back in time, to an age when the planet’s biodiversity was untouched. “It’s like, wow! This is what Earth did look like back then.”

Now she is fulltime at Galapagos, with a professional role as Director of Marketing and Communications at the Charles Darwin Foundation (CDF), a scientific research organization tasked with safeguarding the historic biodiversity and ecosystems of the archipelago.

Tanty-Lamothe speaks five languages. Born French, she was raised in Holland and her professional life saw her as an Executive and later a Director with Brunswick in London and São Paulo. She later served in Amsterdam as Senior Communications Director at COFRA, an investment group promoting responsible and sustainable business practices. In 2022, she left the corporate world and moved with her husband and child to the Ecuadorean islands. There, in her new position at the CDF, she’s extending the foundation’s reach internationally and locally, including through collaborations, education and exhibitions.

With two airports and a growing population numbering over 30,000, the Galapagos Islands don’t look quite the same as when Darwin first brought them to international attention in the mid-19th century as part of his research behind the theory of evolution, outlined in The Origin of Species. But management efforts to preserve the islands since the 1950s have been ahead of their time. Today, the location continues to be an important symbol of the natural world, and a scientific and cultural treasure for communities across the planet.

During a recent visit to the US, Tanty-Lamothe took time to speak with us in Brunswick’s New York office about her new role and the work being done by CDF. With the islands as a platform, she hopes to help push corporate leadership to take a more active stance on biodiversity.

Ambre Tanty-Lamothe, Director of Marketing and Communications at the Charles Darwin Foundation.

So how did you come to work at Galapagos? Your husband is from there, right? That’s where you met?

Yes, I was scuba diving and he was my dive guide.

It sounds like something out of a romance novel.

No, it wasn’t like that. I think COVID was actually the reason. We just kept in touch after I went back to Amsterdam, and then because of COVID, everything stopped in Galapagos. No tourism. Everything shut down. There was no diving going on. So we saw an opportunity for him to come to Amsterdam. And that’s where our relationship really developed.

A holiday turned into living together and having a child together. Eventually I decided, maybe now is the time to go to back to Galapagos. It was a dream. Having visited as a tourist, Galapagos does something to you. You want to be a part of protecting it and also of telling the world what it could look like if you conserved it well. I got very lucky though when this job opened.

What does your role entail?

It’s a new position. I handle communications and marketing to help position the foundation as a key player in the Eastern Tropical Pacific region—international collaboration is critical for us. I also oversee the environmental education team, which works with the local community in particular, and the Institutional Promotion Team, which runs an exhibition center and a shop that is important for revenue. We receive about 75% of all tourists that come to the Galapagos.

How difficult is the international communication from such a remote location?

It’s difficult. That’s why trips like this one are really important. I’m here for a board meeting, but I’ve been spending my last few days meeting with key journalists covering biodiversity, climate change, science—giving them the opportunity to get to know us. There’s a huge amount of interest everywhere in Galapagos. But making that human connection is so much better than just sending an email.

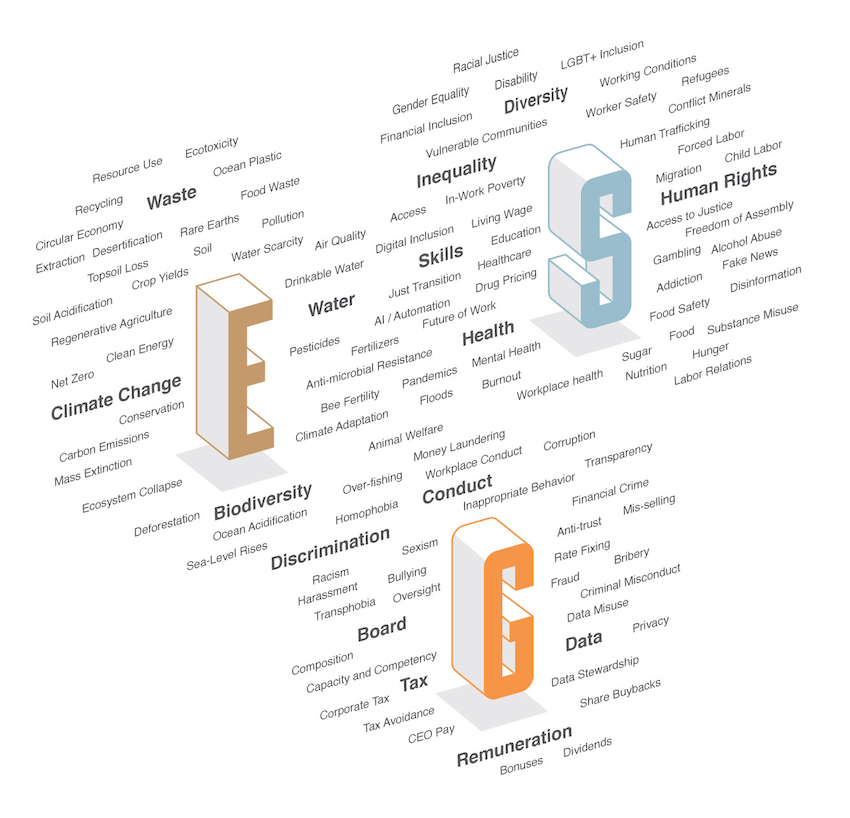

Corporates and corporate media I’m finding are still very focused on net zero, emission reduction, and they’re not quite there yet on biodiversity. That’s something corporates down the line will need to shift. It’s not just about philanthropic money, but it’s also in terms of the voice that they lend to the issue, making sure their business respects biodiversity and contributes to it. Obviously reducing your footprint to net zero is a great step. But focusing on net zero creates tunnel vision. I would like to help convince the corporate world that they need to contribute to biodiversity, open that vision up from looking just at net zero or being climate neutral.

Found only on the Galapagos Islands, the marine iguana is the only lizard on Earth that spends time in the ocean.

How much leverage does the CDF have in the preservation of the Galapagos Islands?

It’s an interesting dynamic and it’s changing. We were founded 64 years ago alongside the Galapagos National Park Directorate, which is run by the Ministry of Environment of Ecuador. They are the entity in charge of managing the national park area which makes up ~97% of the land mass. We’re their scientific advisor; we inform them. We were created as an independent scientific entity under the auspices of UNESCO and IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature). We don’t get funding from the Ecuadorian government. We provide independent technical expertise that feeds into the park, which is the management entity.

We are at an interesting point right now, where we are more and more taking a stand ourselves toward helping advocate and helping biodiversity. We’re implementing together with the park and the government, not just advising.

There are a lot of other NGOs that operate there, and some academic institutions. So it’s a much more diverse and competitive landscape, but also very collaborative. Everyone wants a piece of Galapagos, because it’s such a high-profile place and it’s such an amazing place to do science. What we’re really advocating for more are large-scale conservation and restoration projects, which you can’t do on your own. Collaboration is just so important. You see that a lot particularly in ocean research right now.

I saw your recent LinkedIn post that the CDF discovered large cold-water coral reefs that hadn’t been identified before.

Yes! In the spring of this year, we discovered a reef on the ridges of this volcano we had no idea existed, with a crater some 50 kilometers in diameter. Understanding these ecosystems and what role they play in ocean health and ecosystem services—what do they do? I mean, these are thousand-year-old corals. They’re pristine and ancient.

More and more now, we’re acting as the main coordinator between organizations here. Now we’ve got Schmidt Ocean Institute here, with super-high-definition mapping technology that maps down to two-millimeter precision. It’s incredible to think that you can map a tiny little organism down there at that level of detail. Earlier this year we also collaborated with Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

There are underwater volcanoes, ridges, seamounts. The Galapagos Islands were formed from volcanic activity that drifts with the movement of its tectonic plate, so there are these thermal vents—it’s very deep. You’re in complete darkness. And around them, it’s teeming with life. Bottomline is there is still so much we don’t know about these deep ocean ecosystems, how they contribute to our ocean’s health. That’s something we’re going to be leading on in Galapagos and the region, in collaboration with others.

How much of a challenge to preservation is Galapagos’ growing human population?

Galapagos currently has a 6% internal growth rate. It’s ridiculous. It’s a small population. That’s why it’s still OK. But at some point in the not too distant future it won’t be.

It’s a delicate balance, because the Galapagos economy depends almost entirely on sustainable tourism, eco-tourism. It’s grown exponentially in the past 10 years—up to about 300,000 tourists coming to the Galapagos every year now. Obviously, that’s the bread and butter for the local population, and much more advantageous for an Ecuadorian. They get paid a lot more, so people on the continent see Galapagos as a great opportunity to make money, to be able to provide for their families. Reconciling this with conservation needs is a difficult question, but one that needs to be tackled if we are to safeguard the islands over the long-term.

“I would like to help convince the corporate world that they need to contribute to biodiversity, open that vision up from looking just at net zero or being climate neutral.”

How do you make the case to them about preservation?

Well, that’s where education comes in. That’s so vital. But it’s also about translating the science into a common language. Scientists have a tendency to stay in their little world and be really technical and complicated. So we translate, making the case that if we don’t have the fauna and the flora that we have, which makes the Galapagos Islands unique, nobody will come here. It will just be some barren islands in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

Galapagos is different from say, Hawaii, in that only 3% of the island is inhabited. The rest is national park. You can’t do anything in that national park except visit, and only so many people at a time, only at certain hours, and to a very few restricted places, accompanied by a trained naturalist guide. Overall, it’s very well-managed. But the internal population growth rate remains a serious concern that needs to be addressed.

Can you talk more about translating the science?

Some of the research is pure applied science that you just don’t try to explain to the general public. There’s massively important research that our scientists do, into novel viruses, for instance. Most people won’t be interested, but the donors and academics, the people that support this kind of research—they get it.

We just published a scientific paper that analyzes the ingestion of plastic and other garbage by giant tortoises around urban areas of the archipelago’s most populous islands. That’s a hugely important study and it’s a compelling story to tell, both to the local and international audience, of just how much plastic there is and how we really need to manage this waste stream, to stop throwing plastic in our environment. So, yes, we have to translate those scientific findings and very dry language into something compelling for the reader.

Does the Galapagos live up to the romance of its reputation?

I have to say on balance it does. It’s like you’re flying back in time to when humans weren’t there. It’s nothing like anywhere else on Earth. Animals are not afraid of you. You’ve got a finch that you have to fight for your cake at the table. There’s this lava trail on our campus and marine iguanas like to sunbathe there. They’re black on black. You almost step on them if you really don’t look down. They don’t move. They’re not afraid. Although there’s been 500 years of interaction between humans and animals it hasn’t yet impacted them in a way that they’re afraid of us. So there is that pristineness and it is a magical experience for visitors.

Anything you miss about Amsterdam or Sao Paulo?

With island life, you have zero anonymity. So you have to get out once in a while, to the continent, to Quito. I miss the culture of a big city. Even the opera. My grandmother used to take me to the opera as a teenager and I hated it. Now I’m like, “Oh I miss this!”

Do you have a favorite species?

I do! More than one. I love the Scalesia tree. I just find it mesmerizing. It’s in the highlands, in the cloud forest. And also the sharks—very majestic. The whale shark in particular, that’s my absolute favorite. So impressive to see this 10-meter-long beast. It’s just so calm and yet super-fast. Gorgeous.