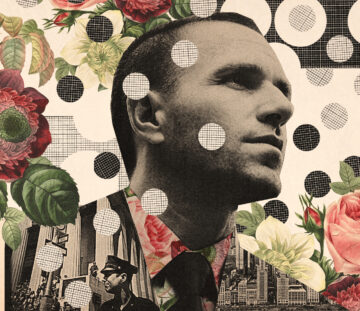

Former FDA Commissioner Dr. Scott Gottlieb talks to Brunswick’s Raul Damas about the evolution of medicine in the US.

In 2017, as the FDA Commissioner designate, Dr. Scott Gottlieb testifies during a Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee hearing.

Dr. Scott Gottlieb, the former head of the US Food and Drug Administration, has recently become what Politico called “the shadow coronavirus czar” in the US, churning out dire COVID-19 warnings and systemic advice in network interviews and Wall Street Journal op-eds. His even-handed professionalism has allowed him the ability to openly contradict announcements from the President—who at first tried to play down the threat—while being spared the political attacks experienced by other former White House officials.

Instead, the Trump administration’s policy has swung to his side, with the President himself retweeting his former FDA Commissioner’s advice, ratcheting up the notice those views receive. Dr. Gottlieb’s own Twitter following has risen from 57,000 last fall to well over 190,000 in recent weeks.

Perhaps the US’s most critical mistake, he says, was in not bringing together the work of academia, private business and government to address the need for tests. As he told CNBC, “There should have been, I think, a sense of urgency about taking an ‘all of the above’ approach and trying to get all of the diagnostic players into the game as early as possible. We ended up doing all those things, but we ended up doing them late. And now we’re still behind the curve.”

That directness and focus on efficiency are characteristic of Dr. Gottlieb. Appointed in 2017, he set a new standard as FDA Commissioner, earning praise for his agency while other offices in the Trump administration were seen to be falling into chaos. After his departure in 2019, he has remained a respected figure in both parties.

In addition to his medical expertise, Dr. Gottlieb has a knack for making complex matters understandable to the layperson and a clear-eyed view of the workings of business, government and media.

In a conversation with theBrunswick Reviewlate last year, before the current crisis was on anyone’s radar, he shared his views on topics related to his time at the FDA, including the balance of government and business, and his approach to leadership.

How did being the son of a physician, particularly a psychiatrist, influence your career choice?

It’s hard to isolate what influence my proximity to doctors had on me. But I was drawn to medicine because of the nature of the profession itself. It meant the opportunity for service and rewarding work, while also offering lifelong learning and the chance to be a part of a profession. I also saw medicine as something that could allow me to continue expanding other interests, especially writing. There is a long history of physician authors. When I decided to pursue medical school, I was already editing my college newspaper. I knew I wanted to continue publishing, even if I didn’t do it full time. I eventually ended up working on the staff of a number of medical journals while I was a student and resident.

How does being a father of three daughters influence your leadership style and policy thinking?

It probably influenced me most directly in how I managed my team at FDA. Many of the people I worked with also had young children. I knew how important it was to allow people some flexibility to work and fulfill their commitments to their families. I understood how important it was to know what people’s boundaries were—when they needed to be offline or adjust their workday to fulfill family obligations. So, I tried to make sure we had a work culture that embraced these needs.

You became FDA Commissioner in 2017. What would have been your priorities in 1992?

The priorities evolved over time at FDA as the opportunity set has changed, along with people’s expectations for the agency. In the early 1990s, a lot of the scrutiny was over the efficiency of the review process. There was discussion of a “drug lag” between the US and Europe. The view was that drugs targeting important medical conditions were being approved in Europe months and sometimes years before they were approved in the US. So, there was a lot of focus on modernizing the review process to move drugs to market more efficiently.

This was also during a time period when FDA was being criticized for not moving to market quickly enough drugs targeting HIV. The outgrowth of that was the FDA Modernization Act of 1997, which created pathways like accelerated approval. In 2017, there were new priorities like opioid addiction, drug pricing, drug safety, and the imperative to help advance new technology platforms safely, like cell and gene therapy and regenerative medicine.

“Things have changed a lot with respect to how information gets shared. I think federal agencies have been slow to adapt but are catching up.“

You first worked at the FDA in 2002, then returned in 2005, and of course in 2017. What long-term changes did you see in the agency?

The most profound change as it relates to new drugs was the growing emphasis on drug safety and significant investment in the agency’s ability to better evaluate the short- and long-term safety of new medicines. I think this is an appropriate reflection of advances in technology. As our ability to evaluate medicines gets better through new tools and science, so should our expectation of the safety of new medicines.

People sometimes say that drugs approved 30 years ago might not be approved today because of our higher bar for safety. I don’t think this is true. Our expectation of safety has increased, but so too has our ability to better define the benefits of new drugs. So, we might be able to reveal more about the safety of drugs that could weigh against a medicines’ approval. But we also know a lot more about a drug’s potential benefits at the time of approval. So, the risk and benefit considerations remain in balance.

What has changed is that we want greater certainty that a drug will deliver its promised benefits. And when there are side effects, we want to know about them quickly. At a time when the technology for evaluating drugs has gotten a lot more advanced, these are reasonable expectations for patients to have.

You led—in many ways ignited—significant medical community concern about e-cigarettes, particularly among minors. What drove you to that decision?

We believed that electronic nicotine delivery systems like e-cigarettes could offer a less harmful alternative for currently addicted adult smokers, to help adult smokers quit cigarettes. E-cigarettes are not safe. But they are less harmful than smoking. And if a currently addicted adult smoker can fully quit cigarettes and transition to e-cigarettes, they can improve their health.

So, we took some new steps in the summer of 2017 to more rapidly migrate adult smokers off cigarettes by seeking to ring e-cigarettes through an appropriate series of regulatory gates. At the very moment we were seeking to regulate nicotine in combustible tobacco, we saw the e-cigarettes as a potential alternative for adult smokers who still wanted to use nicotine but would no longer be able to access it from traditional tobacco.

What prompted us to change our policy as it related to e-cigarettes was the data in 2018 showing a tragic and shocking rise in the youth use of these products. We did not foresee that magnitude of an increase in youth use of these products. In 2017, when we first advanced our policy, youth use of e-cigarettes was declining. The big uptick in kids use of e-cigarettes was shocking to us and was a public health crisis that required strong and immediate new steps.

What does the US healthcare system receive insufficient credit for doing well?

We deliver very good advanced care in the US and benefit from new medical technology. I think we take for granted how advanced our care is for serious conditions. We take for granted how much innovation is developed largely if not entirely for the US market, and how much Americans benefit from these advances. Without the investments we make in advanced care, we may not have the same medical innovations that we’re benefiting from. American consumers drive innovation.

Where we sometimes don’t succeed is when it comes to routine care and a lot of tech-based interventions. We do medicine really well at the high end, where patients have serious conditions. Where we sometimes don’t do a good job is on the more routine aspects of primary care.

“People sometimes say that drugs approved 30 years ago might not be approved today because of our higher bar for safety. I don’t think this is true.”

You’ve been most prolific commenting on the drug industry, but you’ve also noted it’s a relatively small percentage of total health spending. Hospitals represent a much larger segment of health spending. How can they change to help lower system costs?

A lot of the cost and inefficiency in the system is on the services side when it comes to the delivery of care in hospitals. It’s hard for government policy to impact these trends. It’s hard to set rules in Washington that are going to drive more efficiency in delivery. Often what we do in Washington drives the opposite result.

Politically, it’s also harder to advance policy in Washington that could be adverse to hospitals. They are distributed around the country and are generally the top employers in their congressional districts. So, the hospitals, as a group, have a lot of political influence on Capitol Hill.

I think as more of the financial risk for the delivery of care shifts to providers through payment bundles and other forms of capitation, that’s putting more pressure on provider systems to improve their efficiency. And you’re seeing at the same time a lot of investment by venture capital and private equity in new delivery models that are aimed at helping offer more efficient arrangements for delivering care, or new tools to hospitals and other systems for enabling these outcomes.

How does medical training need to change?

Medical training already has changed. Medical students today are much more likely to embrace arrangements where they are employed by systems as opposed to being independent. When I was training, everyone wanted to own their medical practice. Today, the majority of medical students want arrangements where they’re salaried employees of larger systems and have more predictable work arrangements. The expectations have changed dramatically, in part driven by the changing desires of graduating medical students, and in part driven by changes in the structure of medicine where the kinds of private practice opportunities that were the norm 20 years ago are no longer as prevalent.

At the same time, I think students are being trained to be much more cognizant of cost and efficiency. This is good, to a point. You want the imperative to be on achieving the best outcomes for the patient. But I think physicians should be accountable for costs to the patient and understand how cost impacts a patient’s access to care—their ability to remain compliant with care—to achieve good outcomes. The system should worry about the system-wide costs. The physician should be focused on their patients and cost incurred by patients is a big factor.

You’ve created a niche for yourself on social media. Your Twitter account has 57,000 followers. Why do you use social media platforms?

Social media has been a very effective tool to engage the public and also get information out quickly. I found it to be invaluable when I was at FDA as a way to do rapid response but also to offer perspective on breaking issues. I think agency heads are going to have to rely on social media channels like Twitter more and more. The news cycle moves so fast that in order to get your information and perspective into stories you need to be able to disseminate it through these vehicles.

Things have changed a lot with respect to how information gets shared. I think federal agencies have been slow to adapt but are catching up. If you wait a day to respond to something important, you could have lost the chance to shape the narrative to reflect your goals and incorporate what you believe are key elements to a story.

—

More from this issue

The WFH Issue

Most read from this issue

The Calculus of Audra McDonald