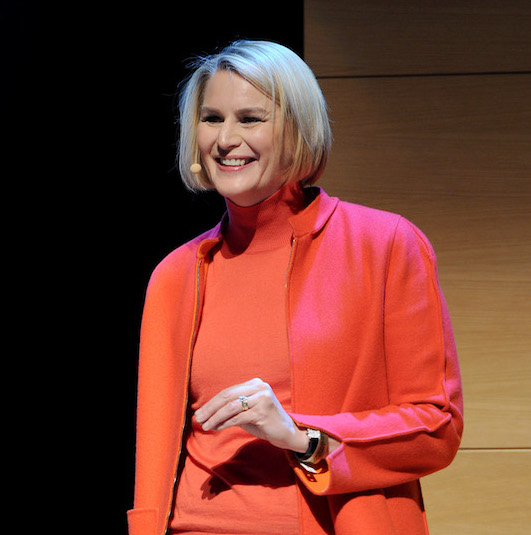

Elaine Bedell, CEO of London’s Southbank Centre, talks about leadership and support of the UK’s largest culture facility with Brunswick’s Esme Castrillo and Fanny Guesdon.

In 2017, Elaine Bedell became the first female CEO of London’s 11-acre cultural hub, the Southbank Centre, since its founding 66 years before. The Chair of its Board was a woman, Brunswick Partner Susan Gilchrist, and women held other leadership positions. Yet the CEO seat seemed like a remaining glass ceiling—until Bedell broke it.

“I like to joke that they had actually run out of men to ask,” she tells us in a recent interview for the Brunswick Review.

Bedell has since guided the institution—and the coordination of its four venues, 14 restaurants, many resident performance companies and national touring programs—through a pandemic, global social challenges such as the Black Lives Matter and Me Too movements, and world-order temblors such as the ongoing wars in Ukraine and Gaza. Such disruptive public events crystallize and reshape Southbank Centre’s fundamental mission: to reflect the concerns of the people through art and culture, welcoming all members of society and granting them inspiration and relief.

That mission goes all the way back to Southbank Centre’s founding at the Festival of Britain in 1951, where it was meant to bring the citizens of Great Britain together for a joyous sharing, after enduring the hardships and destruction of World War II.

“The Festival was, in itself, a positive vision of our national story through the lens of arts and music and science and ideas,” Bedell says. “After five or six years of war, it was a celebration for everybody, not just a privilege of income, and provided a way of looking much more positively at the future. The Royal Festival Hall is the only remaining building from the Festival and around it, the Southbank Centre has grown into this incredible cultural campus.”

Royal Festival Hall is one of the primary and most well known of Southbank Centre’s four major venues.

On the banks of the Thames, Southbank Centre today is the UK’s largest art center, an important cultural base both for locals and for the entire nation. Its river-facing facilities host a huge number of global performers and celebrities, also making it an international tourist attraction. Chaka Khan, Paul McCartney, Ru Paul, Hillary Clinton and former US First Lady Michelle Obama have all appeared there and it is home to six resident world-class orchestras. A comprehensive survey of recent sculptural work by South Korean artist Haegue Yang opened in October; next year will see British icons Gilbert and George host a big survey of their work.

Beyond the Royal Festival Hall, Southbank Centre hosts three other iconic venues: the Hayward Gallery, the Purcell Room and Queen Elizabeth Hall. It is also home to the National Poetry Library. Hundreds of other ensembles, musicians, poets and dancers perform there.

We spoke to Bedell about the challenges of leadership that she has faced during her tenure. She credits her success in no small part to the supportive role of other women—friends, colleagues and mentors.

You’ve led considerable change at Southbank Centre, in a challenging environment. Can you tell us about this transformation and its impact?

I arrived with a strategy in mind that involved some transformation, but of course, it turned out to be quite different, largely because of the pandemic. Then there were global circumstances, challenges on finance, the war in Ukraine—things beyond our control. The leadership that I needed to have was perhaps a lot more flexible, a lot more transparent, a lot more open, certainly in terms of communication with the staff, because we were going through an unprecedented rollercoaster of change.

The leadership models I experienced when I was starting out would simply not work in the modern workplace. Leadership has changed, and what staff want of their workplace and from their leaders is fundamentally different. It’s been really exciting and rewarding to go with that, to work out what a modern Chief Executive looks like in these times.

What do employees expect from their leaders now?

We might talk about work-life balance for one. I started my career in television and was ambitious to do well, but I was equally sure that I wanted children. I needed to try and accommodate both and I was just doing what I could to muddle through. By the time I had my second baby, that involved me literally putting her in a Moses basket under my desk, because I was also breastfeeding, so she needed to be where I was. When I tell this story to young women that I mentor now, they’re completely horrified. Those do not look like good lifestyle choices now. It worked for me at the time, but I honestly couldn’t advocate it as a model for everyone.

“I’m proud that we’re the fifth most visited attraction. I’m proud that we have built our earned income. We’ve grown it by 20% just in the last year alone.”

Particularly younger staff now expect to have a proper work-life balance. That is incredibly important to them when they’re deciding what roles they want to take up and what organizations they want to work in. It is important as leaders that we accommodate that as much as we’re able to.

So I think flexible working is here to stay. We are a kinder, more welcoming place for women specifically—all generations of women. I introduced a menopause policy here. We never had one before. Hardly any organizations did. It’s easier for older women in the workplace now to acknowledge some of the things that they’re going through and that they may need time to work through that.

Also, the sort of old-school notion that, as a chief exec, you’re paid the big bucks to carry all the responsibility and all the information, that no longer really works. Things move too fast. There’s too much information out there. It’s really important that you are as transparent as is appropriate with staff, that you explain all the time—you’re very, very clear about strategy, you’re very clear about the goals that you’re working towards, you’re very clear about the KPIs. Those messages are clearly reinforced all the time, so that everybody has a clear sense of the journey that they’re going on. The time when you could say, we will do this and I’m not explaining, it’s my decision—I think those days have long gone.

How do you respond to social change as a leading cultural institution in the UK and yourself as the leader?

Well, the really important thing is that arts organizations should be absolutely in the conversation about social change. Arts and culture are fundamental to society’s well-being, to its psyche, to its growth. When you think about the opening ceremony of the London Olympics in 2012, that so brilliantly told a story about the birth and the growth and the development of the British Isles.

That’s what art and culture constantly does. It tells our stories. Arts and culture are nothing if not relevant—they’re reflecting back at communities how they are feeling. We don’t necessarily need to be political with a big P, but we do need to be talking about the stories and issues that matter, to give artists the space to do that in their own words. So the really important thing at Southbank Centre is that we give artists the platforms to do the very best art that they can do and, whatever their kind of vision is, that we give them the space to deliver.

How does the structure of the organization and its programming reflect that conversation?

The Southbank Centre is the fifth most visited attraction in the UK—20 million visitors a year, 3 million buying tickets to our events, a very, very broad cross-section of the population. We are in the heart of London, but we’re also a national organization as the second-highest funded Arts Council England organization, and we partner with organizations outside London. We have a touring program that goes to regional art galleries. We have a responsibility to represent people and artists across all communities.

At the same time, we’re also quite local. We are Lambeth’s local art center—Lambeth being one of the poorest London boroughs, with a lot of social issues, but also a lot of really vibrant, wonderful communities doing amazing work in the artistic sphere. We want them to feel that all this space that we’ve got along the River Thames also belongs to them.

We’re this really interesting mix of world-class performance, everyone from Stravinsky to Stormzy. But the extraordinary South London jazz scene also grew out of us initially giving rehearsal space to a South London collective, Tomorrow’s Warriors. So we want those communities to also feel that they can use our space.

One of the ways that we ensure that we properly reflect all communities is that 40% of the 3,000 events we do every year are free—even coming out of the pandemic, when our finances were so challenged. I got the support of the board to continue that. That is a way of opening the spaces to different communities who are not maybe familiar with us. They might decide to come to the Centre for some warmth or for a cup of tea, or to have some peace and quiet, and will bump into a choir singing or some dance and will be able to enjoy it for free.

Access is a really important thing for us. Southbank was the first-ever organization to have an open foyer policy. We open the doors at 10 o’clock every morning, and anybody can come in and use our spaces, and they can stay there till 11 o’clock most nights, if we’ve got performances. So you don’t need a ticket. It doesn’t need to cost you anything. We’ve been doing that since the mid-1980s.

There are so many discussions around how tough it is for the cultural sector and how many difficulties there are. Is there a story about positive change and opportunities?

Yes, so you’re right, the funding for arts in the UK is very challenging. We are the beneficiaries of some generous public funding, but we get no help on capital. The Royal Festival Hall is grade one listed and it belongs to the government, not to us. It’s leased through the Arts Council England to us from the government. So we do urgently need money spent on capital, we do need a sustainable strategy of how all these really important heritage sites, like ours, are going to be protected in the future.

Southbank Centre began with public funding, as a temporary site and to that, over the decades since, has been added this extraordinary combination of public and private funding. We now have 14 bars and restaurants on site—that’s a vital entrepreneurial, commercial addition to the funding that we get.

“The way that I survive as a leader is by being surrounded by other incredibly supportive women.”

Our cultural campus is 11 acres, it extends from the London Eye to the National Theatre, along the River Thames. We’re a creative hub—and were before it was fashionable to talk of creative hubs! We’re responsible for about 1,500 jobs at Southbank Centre in our cultural ecosystem—we’ve got partners who use our spaces for performance, music making, commercial activity, all the contractors who work out of here, all the community groups who use our spaces. Creative industries actually account for 6% of the total UK economy and the cost to the government of arts and culture is virtually nothing. The return is extraordinary.

And it’s not just about the art. Backstage, the most extraordinary work goes on with visual effects, with lighting, with sound, so we’re also running a technical academy where we’re training people to go into backstage skills. And we’ve deliberately targeted women and lower-socioeconomic entrants into that scheme because it is quite a male-dominated sector. We’ve also been training people and losing them to film and television who can afford to pay better than the arts. That’s a success story for them and for us. We’re proud of that. What we have to make sure is that we continue to bring new entrants in and train them to provide that bedrock experience for careers. They may go on to Hollywood or the West End, but you know, they begin quite often in subsidized arts organizations.

What are you most proud about having achieved since you’ve been Chief Exec?

I’m proud that we’re the fifth most visited attraction. I’m proud that we have built our earned income—we’ve grown it by 20% just in the last year alone. I’m proud of appointing the brilliant Mark Ball as the Artistic Director and the amazing artistic program that we’ve had. I’m proud that we were the place where Michelle Obama chose to come, where Chaka Khan did her “Meltdown,” and where Marina Abramovic did her extraordinary Institute Takeover.

I couldn’t possibly name all the events that I’m proud of, but we are still producing at least three events every single night across our venues. I’m very proud of how extraordinarily resilient we’ve proved ourselves to be over the last seven years.

Do you ever get a moment to stop and reflect on your leadership style and whether that’s changed, and what the most valuable lessons are to you in your job?

I’m very grateful to women. I had female role models. I was lucky enough to have female role models throughout most of my career inside the BBC. When I first joined as a young producer, there were women in BBC Radio doing quite senior jobs—I’d never come across women like them.

The way that I survive as a leader is by being surrounded by other incredibly supportive women, including my best friends, former colleagues and my sister. Whether you are a working mum or not, if you’re a female leader, it is really important to have a close circle of people that you can rely on, who are not judgmental, but are just there for you at the end of the day. And I’m very lucky, I feel, that I have had those women in my life.

Fanny Guesdon is a former Brunswick Director in Strategy and Planning.