Long-ago sacrifices still frame contemporary commitment to Singapore and Southeast Asia. By Will Carnwath, co-founder of Brunswick’s Singapore office.

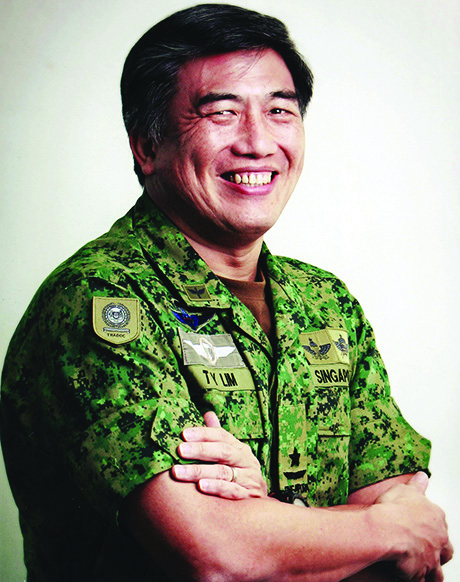

Lim Teck Yin and I have known each other for a couple of years now. He is a former Singapore national team water polo player and later a special forces officer, finishing his army career as a Brigadier-General. From 2011 until this April, he was CEO of Sport Singapore, the country’s lead agency for sports. We worked closely when Brunswick supported a restructuring of the ownership and control of SportsHub, which includes the new Singapore National Stadium.

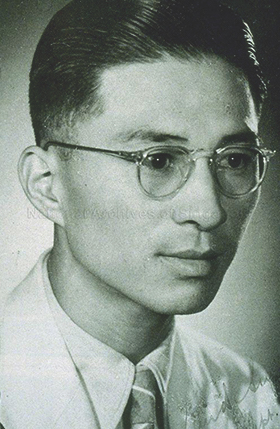

Yet it wasn’t until recently that we realized we had something else in common: We are both grandsons of men who served with distinction in horrific circumstances during the last years of World War II, here in Southeast Asia. Teck Yin’s grandfather, Lim Bo Seng, said goodbye to his family and enlisted to fight the Japanese in Malaya. He served in Singapore as a covert agent—an extremely dangerous assignment that provided critical intelligence and ultimately cost him his life. He died heroically as a prisoner, protecting his contacts to the last and starving himself in an act of protest over the conditions in which his fellows were being held. His death did, in fact, lead his captors to improve the prisoners’ treatment.

My own grandfather, Percy Salkeld, was running Steel Brothers, a British-Burmese export business, based in Yangon. When the city fell, he was given a field commission to Lieutenant Colonel and, as the British military retreated and Japanese bombs fell, asked to lead an evacuation of both Steel employees and their support community. It became a harrowing four-week walk through the jungle, out of Myanmar to India—an ordeal still talked about, not just in my family, but in the families of hundreds of people involved along the way. For a large part of the journey, he commanded a troop of elephants and handlers that became “walking hospitals,” carrying supplies and picking up the sick and wounded they encountered. He was later awarded a CBE for “services to refugees during the evacuation of Burma.”

Those experiences, remote in time, are small parts of the foundational story for what Singapore and Southeast Asia are today. In tangible ways, they have also influenced the values and ethos that we both seek to embed in our own teams.

“To a large extent, whenever my grandfather was discussed, it was always a conversation around values,” Teck Yin says when we discuss it. “Values of education, values of discipline, values of filial piety. His sense of values, his sense of responsibility to a larger whole, enabled him to make the ultimate sacrifice. That was something that shaped my outlook, even my entire 42-year journey in public service.”

Sadly, I never got to hear the story directly from Percy, but his letters from the time, and now the published accounts of that evacuation, are full of moments when, with hardships and obstacles arrayed against him, he held firm to optimism, determination and humility. His commitment to even basic routines (his men shaved every day of that brutal journey, for instance) was symbolic of the values that he refused to let slip. His sense of humor stayed firmly intact amid outrageous frustration. That integrity was evident in the compassion he showed the people he met, rescued and protected along the way.

Percy was low-key about the hardships—pouring rain, illness, floods, lack of food and medical supplies, blisters, insects …. “It was a march more good for the soul than the body,” was his only concession to those trials in his letters. “And as I remarked on one or two occasions to cheer the party up when trying to camp for the night in rain—‘good practice for worse!!’”

Our grandfathers found a resilience and a grace they perhaps hadn’t fully known before, because of the extreme conditions to which they were subjected, and because they were never focused on themselves but on helping others. That legacy, which has come down to Teck Yin and myself, has left us with a deep and personal commitment to Singapore and the region, and a sense of ownership for the culture of the teams we lead, a responsibility to the future, to do our part.

“My decisions and sacrifices pale in comparison to what he was asked, what he felt compelled to be,” Teck Yin says of his grandfather. “But it has always been clear to me that the future of Singapore depends on Singaporeans who have that deep understanding of the value of this place we call

our home.”

More from this issue

Southeast Asia

Most read from this issue

All Roads Lead to Singapore