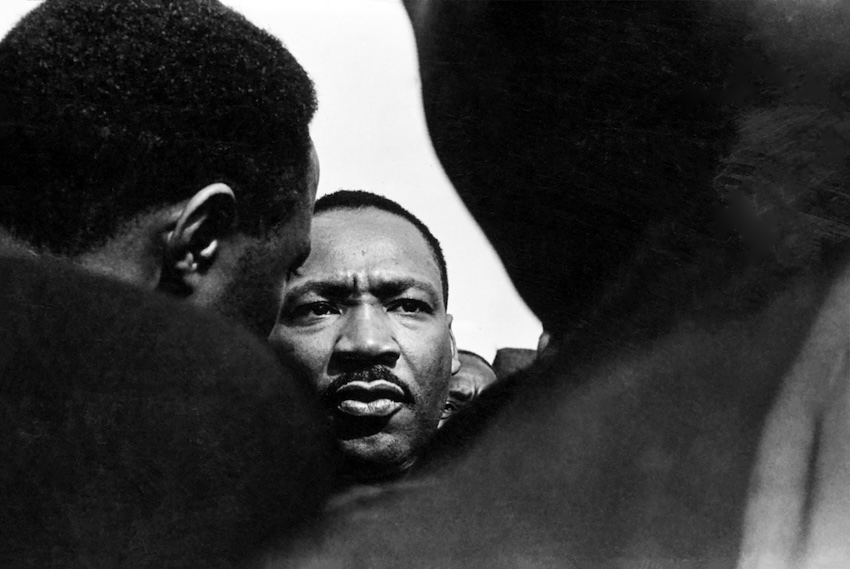

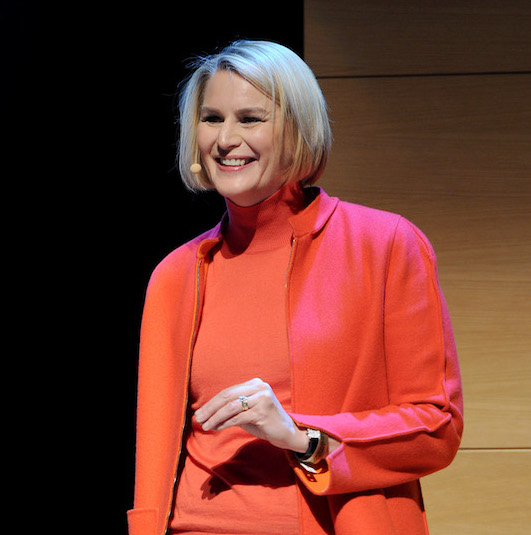

When it comes to how, when and why we work, McKinsey’s Chief People Officer is the voice of the future. By Michael France and Noam Safier.

Long before Katy George became McKinsey’s Chief People Officer in 2021, she was focused on people angles. In a 2018 video, for instance, she argued that low wages aren’t the primary attraction for US manufacturers moving operations overseas. “They’re going outside to find more skilled workers, to find more modern factories, to find companies better at using new technologies and automation,” said George, a Senior Partner at McKinsey. “By investing in our workforce capabilities and new technologies, we can reverse that.”

Her years of experience as a McKinsey consultant and first female to lead the firm’s Operations practice means that George brings an operational mindset to her role as Chief People Officer. To increase productivity, morale and retention, what works? Demonstrably? Provably? In the wake of a pandemic that obliterated traditional patterns of work, such questions have never been more relevant.

“I feel really privileged to be in the talent space during this once-in-a-multi-generational kind of disruption in talent models,” she says. “When things are thrown up in the air, we have the opportunity to shape how they come down again, and hopefully make things better.”

As Chief People Officer of a global firm with more than 40,000 colleagues, George is able to use McKinsey as a giant laboratory, employing the outcome-tracking skills she developed as a consultant to examine the most pressing talent-related questions facing business: How much flexibility is ideal? What is the impact of flexibility on productivity, on quality, on client feedback, on team-skill acquisition? What are the labor implications of Generative AI?

Other firms armed with such insight might keep it proprietary. But McKinsey is in the business of sharing advice and insight, and George in particular stands out for her ability to connect with audiences both live and online. The holder of a Ph.D. from Harvard in business economics, George is a 28-year McKinsey veteran, and a proud mother who enjoys making a five-layer Kahlua chocolate cake. George spoke with Brunswick’s Michael France, a Partner in the firm’s New York office.

It sounds as if your research will please neither those who want a near-complete return to office nor those who want near-total flexibility.

Our research, during and post-pandemic, suggests that people, now more than ever, demand work that’s connected to purpose. Individual purpose. Purpose of the employer. That used to feel soft and fuzzy. Now, as employers, we’re all experiencing it as “edgy.” People are also demanding more flexibility around in office/not in office, and also in their own skill development. They are demanding more control over their career path and their career opportunities over time. “Have I learned something?” “Am I building skills?” “Am I becoming more marketable?” “Am I working toward my goals of what I want to do with my career?”

We have researched how different choices that our teams make play out in terms of outcomes. We have a unique kind of sandbox. With 4,000 teams around the world, we can experiment and measure to find out where they’re working and how they’re working, and the effect on outcomes.

Our research shows that teams that were together at least 50% of the time experienced significant increases in the excitement of the team, in the sense of connection and belonging, and in retention. We see real evidence that these people grew, in terms of their skills and apprenticeship opportunities, more than if they were working primarily remotely. By 50%, that’s over the course of a multi-month period. It doesn’t necessarily mean two days a week.

In addition, every year we survey all of our colleagues to ask, “Who are your sponsors and mentors?” “Who is making opportunities for you?” We also ask about the satisfaction with the support that they’re getting. What we find is that colleagues who are primarily remote have the same number of sponsors and mentors as the people who are in person—but the satisfaction is much lower. In terms of the kinds of opportunities that people are getting, our research shows those who are in person at least 50% of the time are enjoying more opportunities to grow.

This is not something we’re imposing. Rather, we share this information, then leave it to each team and team leader to try to devise schedules that maximize people’s flexibility when it’s needed, but also gets people all together in person enough to drive all these great outcomes.

“When things are thrown up in the air, we have the opportunity to shape how they come down again, and hopefully make things better.“

What’s super-interesting is that greater than 50% in person doesn’t produce a linear increase in all of those great outcomes. We’re gathering more data that could change or complicate the picture. But our initial research suggests that there’s a magic sweet spot in being in person half of the time over the course of months. There is anxiety around winners and losers, around whether we’re going to make people come in. But what really matters is how you’re creating collaboration, fostering innovation and providing helpful feedback.

Some assignments—those requiring intense individual focus—may best be done remote. On the other hand, our research shows that in a remote environment, it’s harder to have tough conversations, and to conduct breakthrough kinds of problem-solving. Our best teams are the ones that are figuring out how to combine and get the best out of both modalities.

Too often, we see companies that force people back to office to do exactly the same work in exactly the same way as they would have done at home—except now they have the hassle of a commute. Forcing people to commute is not going to nurture a great culture, a great sense of belonging or a great level of productivity. That’s when people will say, “I’m going to look for a different job where I don’t have to do this commute.”

It has to be about changing the way you work, and really being thoughtful about the kind of work you do in person versus remote. There are clear benefits from different ways of working, and you should take advantage of all of those.

Do the benefits of in person versus remote vary according to where you are in your career?

Oh, 100%. Often, when we’re talking about culture, we’re really talking about in-person apprenticeship—seeing how people do things, how they behave in a meeting, being able to talk about it in the hallway afterward.

Our younger colleagues, people who are beginning careers, have lost out by not having those experiences. Certainly, those of us who are more senior often find we can be very productive by Zoom, but we’re drawing on the social fabric that we had established previously. But no matter where we are in our career, we are all still learning and we need to learn from each other. That social fabric is core to how we interact, how we have tough conversations, how we live by great values, how we form alliances and alignment in order to get good work done. That requires serious investment and I don’t think we’ve found a substitute for in-person.

I also think we’re already seeing a reinvention of work—more offsite, more meeting events expressly for the purpose of creating that social fabric while getting stuff done. As opposed to, “You must come into the office to sit on Zoom calls all day.”

People at all levels must be more purposeful about reaping the benefits of being in person. “How do I make sure I get those benefits?”

The most acute losses in an entirely remote environment are definitely for early-career folks. But senior, more-established people have also experienced gaps from the loss of in-person time together, such as a breakdown in vital social networks or learning new skills.

I know you’ve written about burnout. How does it play into this calculus?

Hybrid work should be something that can support better mental health and better life-work sustainability. But I think we’re still learning how to really do that and to change our work practices to do it right.

At first, many of us thought working at home would give us more time to exercise and so on. But quickly we found that, actually, we were working round the clock without the geographical transition that used to help keep us sane. Then you see all of the studies about how Zoom meeting after Zoom meeting after Zoom meeting can create its own kind of burnout. There are some downsides to manage.

“Hybrid work should be something that can support better mental health and better life-work sustainability. But I think we’re still learning how to really do that.“

How is GenAI going to change our discussions not only about where we work but how organizations are designed?

There are still a lot of open questions: Will we need more experts or fewer? I’m not sure yet. I heard somebody make a very passionate case for why people will need to have even more deep expertise. I’m not sure about that. Actually, they need to be better integrators and questioners.

At McKinsey we’re aware that if we decided to substitute all of our junior consultants for GenAI, soon we would not have senior consultants. We also know that GenAI cannot do some of the work that senior consultants are doing, in terms of really counseling CEOs. Certainly all consultants, including senior people, can be aided by GenAI, but there are things that GenAI cannot do.

This is my personal view, it’s not a McKinsey view, but when you look at other innovations that were supposed to be huge productivity-enhancers, what you saw was a dramatic change in the way we work. But it didn’t actually take a lot of work out of the system.

With the advent of email, many said, “Oh, my gosh, this is the most incredible productivity-enhancer. We’re going to have to go down to working three days a week.” What happened? We just do more work, and that work is value-add. Well, some could argue whether the extra work is worth it. But we basically hold the bar higher for what we are going to get done and we use the productivity tool to do that.

I remember seeing a study of washing machines and dishwashers and vacuum cleaners when they came out in the 1950s. At the time, people thought, “This will be unbelievably liberating for the housewife. She’s going to play tennis all day.”

What happened? The world moved from a once-a-month cleaning cadence to once a week.

I think our junior people will find wonderful things to do using GenAI, and we will be looking for junior people who are great at using GenAI and who stay on the cutting edge of that. For McKinsey, my hope is we’ll see junior and senior people spend a lot more time with clients, in terms of really coaching and helping drive implementation, drive learning, drive alignment in ways that we’ve always said, “Oh, we wish we had more time to do that.”

By the way, McKinsey has developed a proprietary Generative AI tool called “Lilli,” which is our first and pretty significant step into GenAI for our consultants. We are still in a trial period but already have something like 7,000 users.

Is there an element of the workplace discussion that you think should receive more attention?

COVID and its effects have put a real spotlight on the fact that we do not have a good way of measuring productivity of knowledge workers. That’s quite a gap. Forever, we have used “watching people work” in our offices as a proxy for “managing productivity.” I hear people saying, “If somebody’s not in the office, how do I know if they’re not just spending all their time with their kid, or shopping?” “How do I know that they don’t have a second screen and second job?” (And we know that’s happening with some employees, right?)

The question should be: What is the expectation of the work that should get done in a day? In a week? In a month? How do you manage expectations in an inspiring way that actually drives productivity and performance? As my colleagues recently wrote in their book, Power to the Middle, this will, in part, mean investing in frontline managers who, due to their unique position between employees and senior management, will have a big role to play in the future of work.

The winners will be those who figure out how to drive real performance through their people.

More from this issue

People Puzzle

Most read from this issue

Social Media and the British MP